While the Bishops were in prison the child was born.

A boy! The son for which the King, Queen, and their supporters had been praying!

There was deep despair among the King’s enemies which could only be tolerated by disbelief.

William preserved his calm. The birth of this child was the most bitter blow which could have come to him but he gave no sign of this. He sent Zuylestein to England to congratulate the King and Queen.

But before Zuylestein left he was alone with William who said: “You know what I desire of you?”

“To discover the true feelings of the people, Your Highness.”

“Find out what they are saying of the King and the Queen … and the Princess of Orange … and myself. Find out what they think about the opportune birth of this child.”

William waited impatiently for Zuylestein’s return.

The Princess Anne wrote jubilantly.

“The Prince of Wales has been ill these three or four days and if he has been so bad as some people say, I believe it will not be long before he is an angel in Heaven.”

When Mary showed the letter to William, he said: “Let them pray for the Prince of Wales in the churches.”

Mary bowed her head. “How good you are, William,” she said.

And she prayed fervently for the health of the child, for secretly in her heart she wanted him to live. These last weeks had made her look fearfully into a future which filled her with dread.

What was happening in England? Were the people in truth turning against her father? If the child died would they deprive him of his throne and if they did …?

She did not want to be Queen of England through her father’s misfortunes. William desired the crown, she knew that; and she wanted to please William. But not through her father’s misery.

She wanted her father to reform his ways and live in peace with his subjects. And she and William could continue in Holland, which was so much more pleasant since she had told him that she would always want him to rule. That had made him more pleased with her than he had ever been before—and all because she had told him that if ever she were Queen of England he should be the King.

But how could she be happy being Queen of England, even if she could give William his supreme wish and make him King, when it meant that she could only do so through the death or disgrace of her father?

And William, she admitted in her secret thoughts, was still the lover of Elizabeth Villiers.

When Zuylestein returned from England, he was triumphant.

“Your Highness, the Prince still lives and his health is improving, but there are many who believe him not to be the true son of the King. They are saying that the birth was mysterious, that just before the baby was said to be born the Queen asked to have the bedcurtains drawn about her; that the baby was brought into the bed by means of a warming pan. The temper of the people is high.”

William sent for Mary. He told her that he was certain the King and Queen had deceived the nation. The child they were claiming was the Prince of Wales, was almost certain to be spurious.

Mary wept bitterly, contemplating the wickedness of her father, and William made a rough attempt to soothe her.

“What is,” he said, “must be faced.”

“William,” she cried, “I can bear whatever has to be faced, if we face it together.”

He bent toward her and put a cold kiss on her cheek.

It was as though a bargain had been sealed.

The rumors from London persisted; there was scarcely a day when a messenger did not arrive at The Hague with a fresh tale. Each day James grew more and more unpopular. The Bishops had been acquitted but their untimely incarceration had increased James’s enemies by the thousand.

There came that day when William sent for his wife. There was a faint glow of triumph on that usually cold face.

The moment had come.

He said: “They have sent me an invitation.”

Mary waited and he who rarely felt an inclination to smile now found one curling his lips. “Danby, Devonshire, Lumley, Shrewsbury, Sidney, Russell, and the Bishop of London. You might say the seven most important men in England at this time. They tell me they will collect forces for an invasion. They are inviting me to go over there … now.”

“To go there, William? But what can you do? My father is the King …”

“I believe that he will not be so much longer.”

She could not look at the triumph in his face. She thought: I am not worthy to be a Queen. I am only a woman.

And she saw her father setting her on his knee and telling those who came to see him how clever she was. She heard voices from the past: “The lady Mary is his favorite daughter.” And his voice: “My dearest child, we will always love each other.”

And now she was one of those who were against him. He would know that. How would he bear it in the midst of all his troubles? Would he say: Once I dearly loved this ungrateful daughter?

She wanted to cry out: He is my father. I loved him once.

But William was looking at her coldly, and his eyes reminded her of her promise always to obey.

Mary Beatrice wrote to her stepdaughter.

“I shall never believe that you are to come over with your husband, dear Lemon, for I know you to be too good that I don’t believe you could have such a thought against the worst of fathers, much less perform it against the best, that has always been kind to you and I believe has loved you best of all his children.”

How could she read such words dry-eyed?

Oh, God, she prayed, let it be happily settled. Let my father realize the folly of his ways, let him confess his wickedness, … and let William have the crown when my father has left this life.

She must not answer Mary Beatrice because she must always consider her loyalty to William. And William was exultant these days although he was coughing a great deal, even spitting blood, and she worried on account of his health.

Sad days! Oh for that happy time when dear Jemmy had danced and skated here at The Hague, and later when she had sat with Dr. Burnet and William and they had all talked pleasantly together. Dr. Burnet had now married a Dutch woman—very rich and comely—and he was happy; and was no doubt thinking of the time when William was King and she Queen and he would be recalled to his native land.

But her father haunted her dreams, his eyes appealing. “Have you forgotten, my favorite daughter, how I loved you?”

I must forget, she told herself, because I have a husband now.

She steeled herself to forget; she prayed continuously. There must be two idols in her life—her religion and her husband.

She must forget all else.

But it was not easy to forget when she read the letters her father sent her.

He did not believe she was in the plot to depose him; he could not accept that.

“I have had no letter from you and I can easily believe that you may be embarrassed how to write to me now that the unjust design of the Prince of Orange to invade me is so public. And though I know you are a good wife, and ought to be so, yet for the same reason I must believe you still to be as good a daughter to a father that has always loved you so tenderly and that has never done the least thing to make you doubt it. I shall say no more and believe you very uneasy all this time for the concern you must have for a husband and a father. You shall find me kind to you if you desire it …”

Mary broke down when she read that letter.

“I cannot bear it,” she sobbed.

Why must there be this unhappiness for the sake of a crown. Three crowns—England, Scotland, Ireland. And so many to covet them!

She went to William, determined to fall on her knees and implore him to give up this design. But when she stood before him and saw the cold determination in his face, she knew that would be useless. As well ask him to give up his hope of the three crowns. As well ask him to give up Elizabeth Villiers.

And she had sworn always to obey; she must obey him. He was her husband and she had promised herself that hers should be an ideal marriage. It could only be so if she obeyed him absolutely.

She changed her plea. “William,” she said, “promise me that if my father should become your captive, he shall be unharmed.”

William had never been a violent man; it was easy to give that promise.

KING WILLIAM AND QUEEN MARY

William was ready to leave for England.

In spite of his ill health—that terrible cough which racked his body day and night and the ever-threatening asthma—he seemed to have grown younger during the last weeks. The dream was about to be realized; and he could scarcely wait for its fulfillment. Outwardly he was as calm as ever; but Mary sensed the inner excitement.

He looked at her intently and with more tenderness than he had ever shown her before. It might be that he understood her feelings, that he was appreciative of this immense loyalty to him which had forced her to turn her back on her father.

He had groomed her well and was pleased with her. Momentarily he thought of the shrinking girl who had been his bride. She was gone forever. She had turned into the docile wife and if he had the wish—or the potency—he could have made of her a passionate woman.

But such trivial dallyings were not for him. He had a destiny and he was about to grasp it in his frail, but nonetheless eager, hands.

“Mary,” he said, taking her hands, “pray God to bless and direct us.”

She bowed her head; this time the tears did not exasperate him.

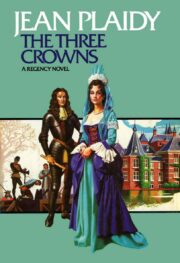

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.