“Never fear, sister. You have been wronged, but we’ll put the scandalizers to shame.” And because he had stood beside her, events had turned in her favor. “Get well,” he commanded, “and join us for the Christmas festivities.”

She had wondered what her reception would be. Because the King had shown her kindness, the Court would—publicly; but that virago, Henrietta-Maria, had insisted that she would not receive her, nor would the Princess of Orange; and they would have their followers. Moreover, James, beset by fears and suspicions, did not come near her, and that was the worst blow of all. She had often since wondered what would have happened if the Princess of Orange had not been struck down with the smallpox. She had died in December, just as the Christmas festivities were beginning; but on her deathbed she made a confession that she had slandered Anne Hyde; and Berkeley, fearing that she had betrayed his duplicity, had presented himself to James and confessed that he had lied.

Berkeley was subtle enough to make a good case for himself. “Your Highness,” he had pleaded, “I was anxious to serve you, and greatly fearing the effects of this marriage on your future, hastened to break it. I would have married the lady Anne and cared for the child for your sake. And it is because I see how heart-wounded you are that I make my confession.”

James was so delighted by this confession of devotion that, with typical Stuart good nature instead of taking revenge on Berkeley, he remembered how they had always stood together in battle and how firm their friendship had always been. He came rejoicing to Anne, begged her forgiveness forever doubting her; and all was well.

And now that child was dead, but she was about to bring another into the world.

But this child would arrive with little notoriety, for the King had a wife and all believed that in a year the marriage would be fruitful; and the child Anne Hyde was bearing on this April day would merely be the cousin of a King.

Now she must retire to her bed for the pains were beginning in earnest.

On the last day of April a daughter was born to the Duke and Duchess of York; she was christened Mary after her Aunt Mary of Orange and her ancestress, Mary Queen of Scots.

In the streets the bonfires burned and the people rejoiced; but it was not the birth of the little girl that the people were celebrating; it was the coming of a new Queen to England—a wife for their merry King, who, they believed, would soon give them the boy who would be heir to the throne.

It seemed in that light that little Mary’s birth was of no great significance to any but her loving parents.

THE FAMILY OF YORK

In the nursery of their grandfather’s Twickenham mansion the two little girls of the Duke and Duchess of York played contentedly together. Three-year-old Mary and one-year-old Anne were completely ignorant of the reason why they had been sent to Twickenham; they did not know that the capital of their uncle’s kingdom was becoming more and more deserted every day, that the shops of the merchants were gradually closing, that people walked hastily through the narrow streets, their mouths covered that they might not breathe the pestilential air, their eyes averted from those tragic doors on which red crosses were marked. They did not know that the King and the Court had left the capital and by night the death cart patrolled the streets to the cry of “Bring out your dead.”

They were, Mary told Anne, in Grandpapa Clarendon’s house because it was in the country which was better than being in the town.

Anne listened, smiling placidly, not caring where she was as long as there was plenty to eat.

Mary watched her cramming the sweetmeats into her little round mouth, her fat fingers searching for the next before the last was finished.

“Greedy little sister,” said Mary affectionately.

Mary had felt conscious of being the elder sister ever since she had stood sponsor for Anne at the latter’s baptism. That occasion had been the most important of her life so far and remained her most vivid experience. Her father had impressed upon her the significance of her role and she had stood very solemnly beside her fellow sponsor, the young wife of the Duke of Monmouth, determined then that she would always look after Anne.

Looking after Anne was easy, for there was nothing Anne liked so much as being looked after. Everything Mary possessed she wanted to share with Anne. She had told her sister that she might hold her little black rabbit, stroke its fur, even call it her rabbit if she wished. Anne smiled her placid smile; but in fact she would rather have a share of Mary’s sweetmeats than her toys and pets.

Mary thought Anne the prettiest little girl in the kingdom, with her light brown hair falling about her bright pink face, and her round mouth and plump little hands. She herself was darker, less plump and more serious. Having to look after Anne had made her so.

Two of the nursery women stood in a corner watching them.

“Where would you find a prettier pair in the whole of England?” one demanded of the other.

“It’s small wonder that their parents dote on them.”

“Mary is the Duke’s favorite.”

“And Anne the Duchess’s.”

“Often I’ve seen my lady Duchess take the pretty creature on to her lap and feed her with chocolates. It’s easy to see from where the little lady Anne gets her sweet tooth.”

The two women put their heads closer together. “My lady Duchess is become so fat. If she does not take care …”

The other nodded. “The Duke will look elsewhere? He does that already, but never seriously. She leads him by the nose.”

“She’s clever, I’ll admit that. It surprises me that she gives way to her love of eating. Did you see the new traveling costumes they were wearing when they left London? The Queen looked well enough in hers … but you should have seen my lady Castlemaine. She was magnificent! Velvet coat and cap … like a man’s … and yet unlike and somehow being more like a woman’s garb for being so like a man’s. Most becoming. But our Duchess! I heard some of them sniggering behind their hands. More like a barrel than a Duchess they were saying.”

The other said: “I wonder when the Court will return to London?”

They were both sober.

“I hear it grows worse. They say that now grass grows between the cobbles.”

They looked at each other and shivered.

Then one said solemnly: “We are fortunate to be here in the country.”

“It’s a little too near London to please me, for they say it is spreading.”

“Where will it end? Do you believe it is because God is angry with the King’s way of life?”

“Hush your mouth. It won’t do to say such things.”

“Well, married three years and no sign of an heir and now this terrible plague. Why if our Duke and Duchess were to have a boy, do you realize he could be King of England? Imagine us. In the nursery of the King of England.”

“And if they shouldn’t and the King not either … well, then, our little Lady Mary would be Queen.”

They stared at the children with fresh respect.

The one grimaced. “That’s if we all survive this terrible plague.”

“Oh, we’re safe enough in Twickenham.”

A third woman joined them. It was obvious from her expression that she brought news which she knew was of the greatest importance.

“Haven’t you heard. Yesterday one of the stewards complained of pains. He’d been to the City.”

“No! How is he now?”

“I heard that he was most unwell.”

The two women looked at each other in dismay; the shadow of the plague had come to pleasant Twickenham.

That night the steward died, and the next day two more of the Earl of Clarendon’s servants fell sick. Within a few days they too were dead. Twickenham was no longer a refuge. The plague had discovered it.

When the Duke and Duchess came in haste to Twickenham there was a tremor of excitement all through the house. The Duke went straight into the nursery and picking up Mary kissed her tenderly before looking earnestly into her face.

“My little daughter is well?” he asked anxiously. “Quite well?”

“Your Grace,” said her nurse, “the Lady Mary is in excellent health.”

“And her sister?”

“The Lady Anne also.”

“Begin preparations without delay. I wish to leave within the hour.”

The Duchess was fondling Anne, feeling in the pockets of her gown for a sweetmeat to pop into that ever ready mouth.

“Well, there is no time to be lost,” said the Duke.

He looked at the Duchess who had sat down heavily with Anne on her knee. She held out her arms for Mary who ran to her and was embraced while her Mother asked questions about her daughter’s lessons. But Mary sensed that she was not really listening to the answers.

The Duke watched his wife and their two daughters, and in spite of his anxiety and the need to hurry he had time to remind himself that he was pleased with his marriage. Not that he was a faithful husband. Charles was furious with him at the moment, because he had tried to seduce Miss Frances Stuart whom Charles’s roving eyes had selected for his own. There was not much luck in that direction, either for himself or Charles, he feared. Arabella Churchill was more amenable, so was Margaret Denham. Ah, Margaret! She was an enchanting creature. Eighteen years old and recently married to Sir John Denham who must have been over fifty and looked seventy. Denham was furious on account of this liaison, but what could he expect? The King had set the tone at Court, so no one expected his brother to live the monogamous life of a virtuous married man.

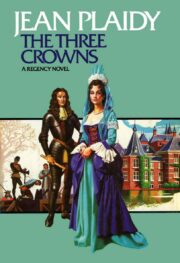

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.