“Edward and Henry are well placed at Court,” went on Lady Frances, “and the girls will now have their opportunity. They will be close companions of the Lady Mary and the Lady Anne, and I shall impress upon them the importance of making that friendship firm.”

“I am sure you will, my dear,” her husband answered.

“In fact,” went on Lady Frances, “I shall speak to Elizabeth without delay.”

She sent one of her maids to find her eldest daughter and when Elizabeth stood before her she surveyed her with a certain uneasiness. Elizabeth was disquieting. Although only ten years old, she seemed already wise; she would be the eldest in the royal nursery and for that reason, as well as because of her character, would attempt to take charge.

“Elizabeth,” said her mother somewhat peevishly. “Stand up straight. Don’t slouch.”

Elizabeth obeyed. She was graceful, but there was a cast in her eyes which gave her a sharp yet sly look.

“The Lady Mary and the Lady Anne will soon be arriving. I trust you realize the honor which the Duke and Duchess are bestowing on you by allowing you to be their companion.”

“Is it an honor?” asked Elizabeth.

Yes, she was sharp, alert, and a little insolent.

“You are foolish. It is a great honor as you know well. You know the position of the Lady Mary.”

“She is only a little girl … years younger than I.”

“Now you are indeed talking like a child. The King is without heirs; the Lady Mary is the Duke’s eldest daughter and he has no son. If the King has no children and the Duke no son, the Lady Mary could be Queen.”

“But the King has sons, and they say …”

“Have done,” said Lady Frances sharply. “You must remember that you are in the royal service.”

“But I do not understand. We are the Villiers.”

“Then you are more foolish than I thought. Even a child of your age should know that every family however important must take second place to royalty.”

“Yet they say that my cousin Barbara Villiers is more important than Queen Catherine.”

She was indeed sly? And how old? Not eleven yet. Lady Frances thought that a whipping might be good for Miss Elizabeth. She would see.

“You may go now,” she said. “But remember what I have said. I should like you and the Lady Mary to be friends. Friendships made in childhood can last a lifetime. It is a good thing to remember.”

“I will remember it,” Elizabeth assured her.

Lady Frances, her daughters ranged about her, greeted the Princesses as they entered the Palace.

She knelt and put her arms about them. “Let us forget ceremony for this occasion,” she cried. “Welcome, my Lady Mary and my Lady Anne. I think we are going to be very happy together as one big family.”

Mary thought they would be a very large family. There were six daughters of Lady Frances: Elizabeth, Katherine, Barbara, Anne, Henrietta, and Mary. Barbara Villiers was a name Mary had often heard whispered; but she did not believe that this little girl was that Barbara whose name could make people lower their voices and smile secretively.

Lady Frances took her by the hand and showed her her apartments. Anne’s she was relieved to find were next to her own. Lady Frances seemed kind but Mary wanted to be back in York with her own mother and the possibility of her father’s coming any day; she was disturbed because she sensed change, and she did not like it. Anne was not in the least worried; she believed that she would be petted and pampered in Richmond as she had been in York.

Mary was not so sure. She was constantly aware of Elizabeth Villiers, who was so much older than she was, seemed so much wiser, and was continually watching her, she was sure, in a critical manner.

Those days became faintly uneasy; and it was mainly due to Elizabeth Villiers.

Supper was being prepared in the King’s apartments. Barbara Villiers, Lady Castlemaine, would be his chief guest; Rochester, Sedley, and the rest would be present; and it would be one of those occasions on which the King could indulge his wit, and afterward they would all leave except Barbara with whom he would spend the night. A pleasant prospect, particularly for a man who had known exile.

It had been said that “Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown,” he ruminated, which was true enough. Not that he was a man to worry unduly. He had had enough of cares and intended to enjoy life, but there was one anxiety which haunted him; he had made a declaration never, if he could help it, to go a-wandering again, and there had been more determination and sincerity behind that declaration than there often was in his utterances.

He could laugh at himself—seeing in the King of England a sinful man. I should be a good King, he thought, if women were not so important to me. But his need of them had been born in him, as it was in James. James would be a contented and happy man, if it were not for women.

We are as we are because we must be, mused Charles. And he tried to remember the stories he had heard of his maternal grandfather, who it had been said was the greatest King the French had ever known; yet he too had had this failing.

It was well enough to love a woman—even if she were not one’s wife. Another French King, Henri Deux, had proved that in a most sober relationship with Diane de Poitiers. But this was different. This was not a woman; it was women. And while he was entertaining Barbara he was thinking of Frances Stuart and the pretty little actresses of Drury Lane—and others. He was thinking too of his poor sad little wife Catherine who had had the misfortune to fall in love with him before she had given herself time to discover the kind of man her husband was.

The trouble was that he was so fond of them all; he hated hurting them or displeasing them; he would promise anything to make them smile, unfortunately promises should be redeemed. Perhaps one of the reasons why he clung to Barbara was that she was ready to rage and scream rather than weep and plead.

These were frivolous thoughts at such a time. His reign had been far from peaceful; what if the people decided that kings brought a country no better luck than parliaments? There was war with the Dutch and it was but a short time ago that his capital city had been devastated by the great plague, when death had stalked the streets of London, putting an end to that commerce on which he had relied to bring prosperity to the land. It had been one of the greatest disasters the country had known; and the following year another—almost as terrible: the great fire.

He knew the people asked themselves: “Is this a warning from heaven because of the profligate life led by the King and his Court?” In the beginning they had loved the pageants, the play, and the magnificence of gallants and ladies. They had said: “Away dull care! Away prim puritans! Now we have a King who knows how to live and if he makes love to many women that is the new fashion.” What amorous squire, what voluptuous lady, was not amused and delighted by such a fashion? “Take your lovers! It is no crime. Look at the King and his Court. It is the fashionable way of life.”

But no one had laughed at the plague and fire and these disasters had revived the puritan spirit. There were still many puritans in England.

But when they had seen the King and the Duke of York working together during the great fire—going among the people, giving orders, they had loved them. It was comforting to contemplate that one only had to appear to win the people’s cheers. In secret they might deplore his way of life but when he was there with his smiles, his wit and, most of all, his cameraderie, he was theirs. To the men he implied: “I am the King, but I am only a man and you are a man also.” To the women: “I am the King, but always ready to do homage to beauty in the humblest.” They adored him, and it was due to that quality known as the Stuart charm.

Poor James, he had missed it. James was too serious. In some ways a pale shadow of brother Charles; in others quite different. James lacked the light touch.

He was relieved that James would not be with him tonight, for James had no place at these amusing little supper parties.

“I would to God Catherine would get a son,” thought the King. “For if she does not then it is brother James who will wear the crown after me and I wonder whether the people are going to love him as they should.”

A smile touched his lips as his thoughts immediately went to Jemmy—beautiful Jemmy, who was wild as all young men must be, and who was ambitious, which was natural too. It was a pleasure to see that young man in the dance—leaping higher than the others—always seeking his father’s attention as though he wanted proof of his affection at every moment of the day. As if he needed it. It was his and he should know it.

“Though, would he be so eager for that affection if I were plain Master Charles Stuart?” There was no need to answer that question. He appealed to women almost as much as they appealed to him; but how many of his easy conquests did he owe to his crown? Most of them, he thought with a wry smile. Young Charles Stuart, the exile wandering through Europe looking for men, money, and arms, had not been so successful as the middle-aged King; and the answer: The Crown! The irresistible Crown!

As the King sat brooding he heard a commotion outside his apartments.

“Let me in!” cried a voice. “I demand to see the King. For the sake of his soul … let me in.”

Charles raised his eyebrows. Surely not another fanatic come to warn him of the fires of hell. He hesitated; then as the voice continued to shout he left his apartment. On the staircase an elderly man was struggling in the arms of his guards. There could not be much to fear from such a creature, he was sure. He said: “Release the fellow. Then perhaps he will tell us what his business is.”

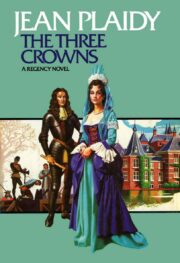

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.