Brandon was soon among his friends and informed them of their mission. “Fitz, you and I shall attack the French flank. Buford, you shall have the left and engage the enemy cavalry. Form the men!”

“Aye, Brigadier!” responded Richard. As Brandon was now senior colonel in charge of a brigade, Richard acknowledged his new role. The two regiments began to get into position.

His message to Lord Hill delivered, Denny dashed back to Wellington’s position when he saw a lone rider heading to the rear. Suspecting a deserter, he flicked his reins and moved to intercept the man.

“Halt!” he ordered as he pulled in front of the rider, his hand upon his pistol grip. “What… Wickham?”

“Denny!” cried a wide-eyed Wickham. “I… I was looking for reinforcements! We have been terribly cut up and—”

“Yes, we know, George!” said Denny, releasing his pistol. “Second Corps is moving to fill in the gaps! And, George, the Prussians are here! They are engaging from the east!”

“But do you know who is coming?”

Denny could well hear the terror in his friend’s voice and attempted to calm him. “Yes, it is the Imperial Guard.” He moved closer to Wickham. “George, if we can hold Bonaparte here by the nose, the Prussians will kick him in the arse. We will defeat him in detail, but only if the line holds—it must! Everything depends upon it. We are concentrating all of our forces here. Wellington is moving in not only Second Corps but the Light Cavalry as well. We will be right here with you, George. We can do it!”

Just then, the sound of horses caught their attention. Vandeleur and Vivian’s men began appearing behind the Allied line. Their mission was twofold: to reinforce the center and to prevent any desertions.

At the sight of the horsemen, all the life seemed to go out of Wickham’s countenance. He stared at nothing for a moment, bowed his head, and then in a flat voice he replied, “I must return to my men, Denny.” He turned his horse and started slowly back up the ridge.

“Of course, of course. Keep your spirits up, George! Until later—bonne chance!” cried Denny.

Wickham stopped and turned his face to his friend. His visage caused Denny to start.

“Good-bye, Denny.”

Wickham spurred his horse forward and loped up the ridge.

Denny could not move for several moments, for the expression on Wickham’s face had shaken him to his core. It was as if he had beheld a man already dead.

The emperor rode his gray horse forward, escorting his five-thousand-man-strong Imperial Guard towards the Allied line. He stopped before the ruined farmhouse at La Haye Sainte and took the salute of his most faithful soldiers. “Vive l’Empereur” rang out repeatedly as they filed by. With a grim look on his face, he waved at his troops.

His confident carriage belied his inner turmoil. He had risked everything to defeat the English before the Prussians entered the battle, but Grouchy, d’Erlon, and Ney had failed him—Ney most of all. He recalled his response to Ney’s demand for reinforcements during his stupid cavalry attacks: “Troops? Where do you want me to get them from? Do you want me to make them?”

Now the Prussians had arrived. Grouchy, whom he had just raised to marshal, had failed to engage Blücher and keep him occupied. Failure and incompetence were all about him.

Yet the emperor still believed in his lucky star. With the fall of La Haye Sainte, the center of the English line was wide open. He could see no troops opposite. Once he split the Allied line, he would force Wellington off the field. He would then turn his attention fully upon the Prussians, a force he had already beaten two days before.

The emperor looked again at the English lines, not five hundred meters away. He saw some enemy troops moving about, but nowhere near enough to stop his Invincibles. With a nod to his still marching men, he turned his horse and rode back towards his headquarters at La Belle Alliance, already planning his assault on Blücher. Victory would be his.

It was 7:00 p.m.

The sergeant looked over as Major Wickham returned to the front lines. “Sir, are there any reinforcements coming?”

Wickham slowly dismounted and entered the pit of death that was supposed to be a square of British infantry. “I understand that Second Corps is moving to link up with the line,” he started in a flat voice. He looked about at the men, lying prone. They were no longer in square; they had again formed lines, as to prepare to receive infantry. “I see we have a few Germans amongst us.”

“Yes, sir. The duke himself brought them. He has ordered the men to lie down. We should only fire at the last moment.”

“Good idea. I suppose we should join them.” They moved a few bodies out of the way and sat on boxes.

“Major, those Frenchies. Are they—?”

“The Imperial Guard? Yes.”

“Sir, are the Prussians here yet? The duke said—”

“Only God knows, sergeant,” replied Wickham. The two grew silent; there was nothing left to say.

The French trumpets reverberated again, along with the strange sound of fife and drums; the marching band was advancing as well. More and more cannonballs fell around the lines. Wickham and his men turned to watch Armageddon approach slowly up the hill.

Brevet Brigadier Brandon and his brigade watched the Imperial Guard move slowly up the rise toward the center of the Allied line about a mile distant from their position. The little bit of woods protected the cavalry from French artillery fire, for the French could not hit what they could not see.

The three colonels of cavalry watched the climax of the battle, waiting the order to engage, immersed in their own thoughts:

Buford: Too often in my life, I have thought only of myself. Now this is my chance to redeem myself—to prove myself worthy of my king, my uniform, my men, my friends—and especially my Caroline. God help me, but this is the only way to wash myself clean of my sins—through the blood of my enemies. I shall earn my place by your side, my beloved!

Fitzwilliam: The French are moving in a rather narrow column. Must take care, but there is an opportunity here. If we can hit them at just the right time, we can cause no little disruption to their plans. Hit and run and circle back behind them. That is the idea. Must keep the men focused.

Brandon: What am I doing here? Marianne was right—I am too old for these sorts of games. Oh my love, what I would give to be at Delaford now with you and Joy! But there is only one road home, and it is before me, through those men there—through Paris. I swore to you, my Marianne, that I should return to you—and I shall. God help any Frenchman who dares to stand between me and home!

Suddenly British troops, hidden from sight along the path, seemed to appear from nowhere. The cloud of musket fire was as good a signal as any for Brandon. Wearing a borrowed Light Dragoon blue coat—something Fitzwilliam had good-naturedly insisted upon—the brigadier placed his hand upon the hilt of his sabre.

“Draw swords!” he called out as he pulled his sabre free. Immediately, eight hundred hands drew eight hundred sabres from their scabbards. The metal flashed in the fading daylight as the swords were first held up, as if to salute the enemy, before coming to rest upon the troopers’ shoulders.

Brandon spurred his horse forward at a walk, not looking to see if the brigade would follow. As a man they all did so, moving slowly out of the woods in a wedge formation.

Down and across the ridge the brigade advanced, the three colonels with but one last thought in their minds: Redemption! Victory! Home!

First at a trot, then a canter, the brigade moved towards the battle, dodging fallen men and animals, cannonballs splashing mud about the field. Finally, Brandon lowered his sword, pointed it towards the enemy, and shouted, “SOUND THE CHARGE!”

Trumpets blaring and regimental flags flapping, a roar arose from eight hundred throats as the men rose in their saddles and leaned over their galloping mounts’ necks, sabres gleaming in the sunset. Mud flying everywhere, Brandon’s Brigade rode towards destiny.

Chapter 28

Pain.

His whole existence was confusion. He was blisteringly hot and then bitingly cold. He was wet with sweat and then dry and feverish. The sky was startlingly bright and then inky darkness. There were horrific screams, there were quiet murmurings, and there was deathly silence. But always there was pain—waves of pain of varying intensity.

The last thing he could remember clearly was the charge. It was a riot of noise and images and smells. The brilliant colors of the uniforms slashed against the gray mist as his horse slammed into the enemy. He struck one cuirassier down, the man’s shiny breastplate offering little protection against his sabre. He ducked just as another fired a pistol, and in the next instant, his sword made quick work of him. Again and again, he struck at men and horses, his arm rising up and slashing down a thousand times, his charger firmly beneath him as he worked like a machine.

And then—everything changed. The left side of his body exploded in pain. After that—blackness.

The rest was a dream—nay, a nightmare. A crushing weight held him down, and wet mud coated his face for what seemed an eternity. Night became day. Shadowy figures moved about him. Loud shouts and gentle arms lifted him. Lifted him—every movement blazing agony. He wondered whether it was his own voice screaming—then blessed blackness again.

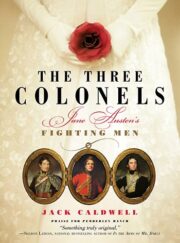

"The Three Colonels" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Colonels". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Colonels" друзьям в соцсетях.