Like the waters of an incoming wave against a rocky shore, the cavalry poured over and around the line, the squares resisting the onslaught. Volley after volley issued from the Allied positions while French cuirassiers and lancers slashed at their tormentors. Finally, the human surge receded, leaving dead men and animals in its wake—and fewer and fewer redcoats standing each time. What heavy Allied cavalry remained harassed their counterparts during the withdrawal.

The artillerymen hastened to their guns. For some reason, the French failed to either spike them or carry them away. Reloading and reforming, the Allies prepared for the next assault, and then the same terrible sequence repeated itself.

Wellington and his staff rode constantly up and down the line, exhorting the men and filling in what gaps they could. When the enemy approached, they would join the artillerymen in the relative safety of the squares. Once, Wickham found himself standing next to Colonel Brandon during an attack.

For two hours, the attacks came and came. Wickham lost count after ten. The crack of muskets and the roar of cannon fire had deafened him. It was good fortune, for he could hardly make out the screams and moans of wounded men and horses. All about him were dead and dying British soldiers; they had no time to evacuate them to the rear. Every time Wickham caught his breath, the French charged again.

“Charge” was a relative term. As the battle wore on, the assaults were made at no more than a trot, as man and animal were pushed beyond the breaking point. On and on, the gallant enemy came. Again and again, the steadfast defenders sent them to their eternal reward. It was no longer war; it was suicide.

About an hour after the attacks commenced, the order was given to “Well-direct your fire.” In other words, shoot low at the horses. It amazed Wickham how difficult it was to carry out such an order. There seemed to be no hesitation in shooting the riders; why was it harder to kill animals than men?

Wickham recalled killing his first man—a charging officer of cuirassiers who was knocked off his horse by the ball from his pistol. By the time two hours passed, he had lost count of the number of men he dispatched by gun or sword. It could be twenty or twenty thousand.

After yet another assault began to fall back, an exhausted Wickham looked about him and saw there were more men down inside the square than not. He turned to speak to Hewitt just as a French trooper spurred his horse, leapt over the dead men before him, and got inside the square.

The next moments were a lifetime to Wickham, as he and the cavalryman fought desperately, but neither was able to land a telling blow. Then, Wickham suddenly found himself twisted around, vulnerable to the man’s sabre. Wickham could not turn in time. Terror seized him. The Frenchman’s sword raised high, and Wickham awaited the inevitable strike—and Hewitt fired his reloaded pistol into the back of the French trooper’s head. The cuirassier fell dead at Wickham’s feet. The terrified horse, now free of his burden, leapt back out of the square and raced headlong downhill.

Wickham enjoyed an instant of elation. He turned to thank Hewitt—and the captain received a musket ball in the belly. Hewitt’s blood spattered on Wickham’s uniform. He caught his wounded subordinate as Hewitt fell screaming.

“Peace, Hewitt, peace! I shall get you to a surgeon,” he lied through his teeth. It was impossible to leave the square.

After a few minutes, Hewitt quieted down, an unworldly calm coming over the captain. It gave Wickham the chance to look up to see if the French were coming again.

They were not. They were retreating.

“Major,” gasped Hewitt, still in Wickham’s arms, “I am all right. It… it does not hurt any more. That is g… good, is it not?”

Wickham somehow knew it was not. “That is good, Hewitt. Hewitt? Hewitt? Oh, God! Hewitt! God damn it!”

Major Wickham carefully laid Captain Hewitt’s inert body on the ground, reached down to the pale face, and closed the unseeing eyes. Wickham took one deep, shuddering breath and looked up. He beheld dead and dying men all around him. There was an overpowering stench of powder and blood and excrement. Beyond was a sea of dead men and animals. Smoke and mist obscured the French lines.

But it was over. He could just make out the retreat of the cavalry towards La Haye Sainte.

A broken Wickham moved a few staggering steps and sat upon an upturned, empty ammunition box, his head in his hands. He was weary, bone-tired from fear and exertion. His ears deafened, and his mind was in a fog. His belly was empty, and his lips ached for water. Caked with mud, blood, and worse, he looked an unholy terror. His heart grieved for Hewitt, the loyal subordinate who had saved his life. He also felt relief—for he had survived and the battle was over. It had to be over.

It was nearly 6:00 in the evening.

Buford and Fitzwilliam watched the whole of the French cavalry assault upon the Allied line, aching to do something to relieve the strain upon the infantry, but it was not to be. Their mission was to protect the left flank and to watch for reinforcements.

“Sir!” cried one of the troopers. “There are men coming out of the woods there!”

The two colonels turned their telescopes to the east; they had been so preoccupied in observing the battle that they had forgotten their responsibility.

“I see them,” exclaimed Richard. “Can you make out the uniform, Buford?”

“No.” It was still light on this late June afternoon, but low clouds and smoke had washed the colors out of the world. “They look gray.”

“They are!” said his companion. “They are here—the Prussians are here!”

Buford swung his ’scope to the right. “We are not the only ones who have seen them.” Masses of French soldiers were marching across the ridge to engage their new enemy.

Wellington continued to ride along the Allied line, escorted by what was left of his staff. To a man, they were distraught at the carnage. The duke was well known to lament losses deeply. As they continued to assess the condition of their defenses, the Prussian liaison informed the duke that the Prussians were engaged with the right wing of the French army. Before the staff could celebrate the good news, disaster stared them in the face.

The squares in the middle of the line had suffered so badly that the proud companies had ceased to exist. Worse, the KGL, badly mauled and out of ammunition after a heroic four-hour stand at La Haye Sainte, had no choice but to quit the farmhouse and fall back to the Allied ridge. The center of the Allied line was wide open. Defeat was at hand, should Napoleon become aware of their weakness.

Wellington was quick to recognize the danger. “Denny! Ride to Lord Hill and have him reposition Second Corps to join up with our right wing! The rest of you—see to the condition of the squares and get all the German troops of the division that you can to the spot, and all the guns, too! I shall order the Brunswick troops to the spot and other troops besides. Ride!”

It was 6:30.

A hated sound floated across the battlefield one last time, forcing Wickham to look up again. He saw that on this occasion the trumpets heralded not cavalry but something far, far worse. Masses of French infantry began forming on the far ridge.

The spotless uniforms on these men were different from any seen on the battlefield this day. The soldiers seemed gigantic, especially with their tall bearskin hats. The esprit de corps of these men was higher than any other French soldiers Wickham had engaged.

Horror seeped into Wickham’s barely functioning brain. He realized that there was only one unit in the French army to which those men could belong. They had to be the Emperor’s undefeated Imperial Guard. His crack division, they were only used when Napoleon was assured of victory; they always delivered the coup de grâce at the end of the battle. They were invincible—they were fearless—because they always won. No army had ever stood before them.

And they were forming before the center of the Allied line.

Slowly Wickham rose to his feet. What was left of his senses fled him. He was utterly broken by the hours of combat he had undergone. Thoughts of honor, glory, and duty were as dust to him. Even fear of the punishment for desertion could not register in his mind. Wickham’s only thoughts were for flight and survival.

Wickham fell back to a horse standing by. Only the grime on his face hid the paleness of his features. To the sergeant holding the reins he shouted, “I am going back for some reinforcements and more ammunition! Stand by your position!” He leapt upon the horse and headed to the rear.

The sergeant was confused, for they had just received a delivery of gunpowder.

“Brandon,” ordered Wellington, “ride to Vandeleur’s position! He is to reposition the majority of his horse to the center! Quickly!”

Brandon rode to the east and soon came upon General Vandeleur and his men riding towards him. Clearly, the general had anticipated the duke’s command.

“Brandon, well met!” called out the general as his brigades continued onward.

“I see you have read the duke’s mind, sir!”

“Yes.” The general gave Brandon an appraising look. “Do you ride, Brandon?”

“I would be honored, sir.”

“Good—take Buford’s and Fitzwilliam’s regiments and protect our left flank! And watch out for our Prussian allies!” With that, the general rode after his men. By this order, Vandeleur had just placed Brandon in command of an ad-hoc brigade.

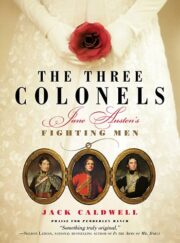

"The Three Colonels" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Colonels". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Colonels" друзьям в соцсетях.