The second reason was that Field Marshal Blücher had pledged to march three whole corps today to join up with Wellington if the Duke would offer battle to the French, giving the Allies overwhelming power.

The question on all the staff’s lips was when would the Prussians arrive?

“The Prince is eager and ready for battle,” offered Denny.

Brandon glanced over at the young Prince of Orange. The hotheaded royal had almost led the Allied troops to disaster on Friday at Quatre Bras. Only the timely intervention of Wellington had preserved the stalemate. Too many of the Belgium-Dutch troops had already quit the field, and the remainders were suspect. That was the reason the majority of the 17,000 troops far to the west at the town of Hal were not British. Wellington needed all the dependable troops he could get his hands on. Still, only a third of the 67,000 men he had were British—and only half of those had seen Peninsular service.

Brandon was nervous about leaving so many men at Hal. If Bonaparte attacked in force, they could never get here in time. Yet “Beau” was convinced that the French would try to turn his right flank and cut the Allies off from Antwerp and the Channel. The duke brushed off complaints, reminding the staff that 80,000 Prussians were supposed to be coming in from the east.

Too much depends upon the Prussians, thought Brandon, as he reviewed their defensive position. The Anglo-Dutch line stretched three miles, from Château de Hougoumont on the right, eastward along the road towards Wavre. The center was anchored by a strong point, a farmhouse at La Haye Sainte, entrusted to crack KGL troops. The left flank was left weak because it was expected that the Prussians would soon come. The heavy cavalry was stationed in the center, and the light dragoons were on the left. The French were thirteen hundred yards to the south on the ridge before La Belle Alliance.

It was a small battlefield, which gave Bonaparte little room to maneuver.

Suddenly there were gunshots from several groups of soldiers, startling Denny.

“Never mind them,” advised Brandon. “Some lads find it easier to clean their muskets by firing them off. Come, let us rejoin the duke.”

George Wickham was in the middle of a barrage of soldiers “cleaning” their muskets, and his ears rang because of it. “Hewitt, tell those fools at least to point their muskets towards the French!”

The last seventy-two hours had been very demanding on Wickham. Quatre Bras had been a fiasco. By the time his force-marched company had arrived, the battle was over. His colonel, curious to see the enemy, had ridden too far ahead and had gotten his fool head shot off. Wickham at first rejoiced, delighted that he was finally free of Darcy’s tormenting agent, before remembering that, when it came to making life difficult for him, Darcy was incredibly resourceful.

A quick rearrangement of officers had made George Wickham a brevet major of infantry in charge of a battalion. Captain Hewitt was now in charge of his old company and was not doing a bad job of it. The rank of major suited Wickham just fine. His job was to order the captains about. It was his subordinates’ responsibility to deal with the rank and file.

The newly promoted Major Wickham and his new battalion marched back towards Brussels in the pouring rain. They made camp at Mont St. Jean during the worst of it, half his men without tents. Wickham hated thunderstorms, and last night’s had been a terror. The only thing that seemed to escape soaking was the gunpowder.

That was a very good thing, he considered, as his eye scanned the opposite ridge.

“Breakfast, sir?” asked Hewitt as he held out a bowl of questionable mush. At Wickham’s look, he added, “Sorry, but it might be the only meal we get for some time.”

Wickham took the proffered plate and choked the gruel down. As he ate, he caught sight of his commanding officer, Lt. General Sir Thomas Picton, riding by, still wearing his civilian clothes from the Duchess of Richmond’s ball. The officer’s appearance made Wickham recall another incident from Friday.

As his men were preparing to leave Quatre Bras, Wickham had nearly bumbled into General Picton. To his amazement, he saw that the general was trying to hide the fact that he was bleeding.

“Sir,” he had cried, “you are—”

“Shut your goddamned mouth, Major!” growled Picton in his usual course, profane manner. “Say nothing about this! You fucking understand me, sir?” He had stared Wickham right in the eye.

Wickham had nodded. Far be it from him to disobey such an order.

Major Wickham stirred himself from his recollections, for the enemy was opposite, and there was work to be done. Handing the bowl to an aide, he stood.

“Hewitt, prepare the men for inspection.”

Colonels Fitzwilliam and Buford prepared their regiments for battle. Their position was on the extreme left wing, a mile and a half from the center of the line. They would be the first to see the approach of their Prussian allies from the east—if they ever got there.

As they saw to their preparations, the two veterans could not help but glance from time to time at the heavy regiments nearby. Unlike the sober and experienced Light Dragoons, the Union and Household Brigades seemed lighthearted and anxious for action. The men in those units came from the heights of British society—and acted like it. Major General Sir William Ponsonby was riding among them, speaking to his men and keeping up their spirits.

Major General Sir John Vandeleur rode up. “How are preparations going, gentlemen?”

“We will be ready, sir,” replied Buford.

“Well, hopefully they will not need us for some time.” The Light Dragoons were held in reserve.

Fitzwilliam lowered his voice. “General…” He gestured with his head at the heavy cavalry.

Vandeleur dismissed his concerns with a shrug. “That is Uxbridge’s problem, Fitz. Let us keep our mind on our duty. Keep a sharp lookout on the flank. Until later!” He spurred his horse into a trot towards the rest of the 4th Cavalry Brigade.

At that moment, the French cannons opened up, and the troops manning the Allied guns dashed to respond in kind. It was 11:30 a.m.

Dorsetshire

Although the grass was damp, Elinor insisted that the planned picnic on the grounds of the parsonage proceed as scheduled, for Mrs. Dashwood and Margaret had made the short trip from Barton Cottage; she would not disappoint them, and Edward would not disappoint her. The blanket spread and Joy merrily occupied by her grandmother, uncle, and aunt, Marianne took the opportunity to take a turn in Elinor’s garden with Margaret. The youngest of the Dashwood sisters had grown into a lovely woman of eighteen, old enough for a serious conversation—one that was sorely needed if what Marianne had learned recently about her sister was true.

Marianne began directly, once they were out of earshot amongst the blooms. “Margaret, do you have an understanding with Lt. Price?” Lieutenant William Price was a naval officer Mrs. Dashwood and Margaret had met while visiting friends. The officer had now returned to his ship.

Margaret colored. “What? I do not know what you mean.”

“Oh, stop it!” Marianne demanded. “Do not play childish games with me! I know he is exchanging letters with Mama, but I believe his interest in Barton lies elsewhere. I asked you, adult to adult, of your attachment to Lt. Price if one exists. This is serious, Sister.”

She looked down. “We have no understanding between us except friendship.”

Marianne breathed out in relief. “That is well. Would I be wrong in deducing that you wish for something more?”

In a small voice, her sister said, “No, you would not be wrong.”

Marianne looked kindly on her sister. “Do you know what you are about, Meg?”

“I do not take your meaning.”

A pained expression came over Marianne’s face. “My love, I am a soldier’s wife. My dear husband is even now in Europe, preparing to face battle.” She stopped and seized her sister’s hand. “Christopher may not return. Do you understand this?”

Margaret’s eyes grew wide. “I… yes, I do.”

“Good. The wife of a man in the king’s service must be ready to lose him to that service. I have learned this the hard way. If you encourage Lt. Price’s attentions, you must face that reality as well. He is a sailor; the sea is his home, upon a man-o’-war. He can only win fortune and advancement through action.” Her eyes became hard. “By action I mean fighting and killing. He may suffer grievous wounds—or worse. A hurricane could sink his ship—”

“Stop it!” Margaret cried. “Say no more!”

Marianne was relentless. “I shall not stop! You are choosing a hard road, Margaret. Lt. Price is a fine man. He would make some woman a fine husband, but she must be one who will support him in his profession. Are you that woman? Are you willing to take the chance that you might lose him to the sea? Think!”

Margaret looked miserable. “I do not know.” She began to cry.

Marianne embraced the girl. “Hush, my love. Shed no tears over an honest answer. Truth can be hard and ugly sometimes, but it is the only path to happiness. Lt. Price deserves nothing less.” She tilted her sister’s head up. “Please think about what you want. I love Christopher enough to risk losing him, for I would never ask him to be anything but what he is. I will support you whatever your choice is. But, if you wish to travel my road, you must do it with a full heart and open eyes.”

Margaret looked at her through her tears. “You mean, you do not object?”

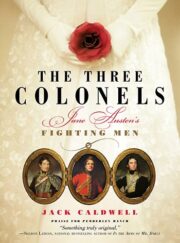

"The Three Colonels" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Colonels". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Colonels" друзьям в соцсетях.