Then I saw a different side to him. He was surprising me all the time.

His knowledge of art was profound as I discovered when we visited the Louvre. He showed me new aspects of pictures I had seen before. He was fascinated by Leonardo da Vinci and we stood for a long time in the Grande Galerie while he discussed the Virgin on the Rocks. Of course he had much to say on the Mona Lisa which had been in the country since 1793; and he told me how Francois Premier, who had cared deeply for artists, had brought Leonardo from Italy that he might have first claim on his works. “He was an artist manque, “he said, “as perhaps I am. But I am afraid there are a good many manques in my life.”

“One which is not, is the wisdom to know it,” I told him.

Such happy days! I shall never forget them. Each morning there was a fresh adventure. This, I told myself, is the way to live. But I reminded myself a hundred times a day, it was ephemeral. There had to be an ending … soon.

But I clung to each moment, savouring it to the full. I had an uneasy feeling that I was becoming his victim as he had all the time intended that I should. I had lost sight of that fact in discovering new sides to his nature.

We went to Pere-Lachaise—so much a part of Paris. I had often wondered who Pere-La Chaise was and he told me that he was the fashionable confessor of Louis XIV and that the cemetery was so named from his house which had stood where the present chapel now did. We looked at the monuments and the graves of the famous.

“A lesson to us all,” he said. “Life is short. The wise make the most of every moment.”

He pressed my arm and smiled at me.

I very much enjoyed the open spaces. I loved the elegance of the Pare Monceau which seemed to be full of children with their nurses and unusual statues of people like Chopin with his piano and figures representing Night and Harmony, of Gounod with Marguerite. The children loved them and when I took Katie there she was loath to be drawn away from them.

It was one day when we were together in the Jardin des Plantes that I realized these halcyon days were almost over. We sat on a seat watching the peacocks and I remembered once saying to him that in certain moments one realizes that one is completely happy. This was such a moment.

I said to him: “I shall have to go home soon.”

“Home?” he said. “Where is home?”

“London.”

“Why must you go?”

“Because I have been away so long.”

”But is not Paris your home, too?”

“One can only have one real home.”

“Are you telling me you are homesick?”

“I just have the feeling that I must go. It is a long time since I saw my grandmother.”

“I hope you will not go just yet. These have been pleasant days, have they not?”

“Very pleasant. I am afraid I have taken up a lot of your time.”

“That time has been spent in the way I wished it to be. You know that, don’t you? These meetings have been as agreeable to me as I hope they have been to you.”

“I will be frank,” I said. “You have a motive, and it may be that you are wasting your time.”

“My motive is pleasure. I find it and that is never a waste of time.”

I was silent. I could hardly refuse him that which he had not asked for … except in a subtle way.

“Why are you pensive?” he asked.

“I am thinking of home.”

“I cannot allow that. Where would you like to go tomorrow?”

“Tomorrow I shall prepare to go home.”

“Please stay. Think how desolate I shall be if you leave.”

”I fancy you would quickly find some other diversion.”

“Is that how you think of yourself… a diversion?”

“No. It is what I intend not to be.”

“You know my feelings for you.”

“You have made them plain.”

“You have enjoyed our excursions?”

“They have been most illuminating.”

“You will miss them when you go away.”

“I daresay I shall. But I am very busy in London. There will be so much to catch up with.”

“And then you will forget me?”

“I shall think of you, I am sure.”

He took my hand. “Why are you afraid?” he asked.

“Afraid? I?”

“Yes. Afraid, you … afraid to let me come too close.”

“I think I may be different from most of the women you know.”

“You are indeed. That is one of the things about you which I find so attractive.”

“So therefore I do not react as you are accustomed to expect.”

“How do you know what I expect?”

“Because I realize the sort of life you have led.”

“Do you know me so well?”

“I think I know you well enough to deduce certain things.”

He gripped my arm. “Don’t go,” he said. “Let us get to know each other … really well.”

I knew what he was suggesting and I was ashamed that it presented some temptation. I shook him off angrily. A love affair? It would be torrid, wildly exciting … until it burned itself out. Such an adventure was not for me. I wanted a steady relationship. A few weeks… perhaps a few months … of passion were no substitute for that.

Suppose he had suggested marriage? Even then I should have hesitated. My common sense told me that I should have to think very dispassionately before I entered into any form of relationship with him. But of course he was not suggesting marriage. He had married once for the sake of the family, and he wanted his freedom now … no encumbrances. He had a strong and healthy heir. He had done his duty to Carsonne. No more marriage for him. He would be free.

I thought: Why have I let this go so far? Why have I allowed my emotions to become involved? I had and I greatly feared that I could be overwhelmed by him.

I looked at the proud peacock, his beautiful feathered tail arrogantly displayed, and the pale little peahen trotting along behind him.

Somehow that gave me strength.

Never. Never, I told myself.

I stood up. I said coolly: “I think it is time that we were going.”

Blackmail

Katie and I returned to London, my father accompanying us because he did not want us to travel alone. I knew that he was relieved because we were going for he had been deeply affected by the Comte’s pursuit—particularly after he had appeared in Paris.

“You enjoyed your visit?” he asked me tentatively.

I replied that it had been one of the most interesting periods of my life, at which he was silent.

It was wonderful to see Grand’mere again. I noticed her studying me intently, and at the earliest moment she found an opportunity of speaking to me alone.

She said: “You look different… younger. I saw the change in you the moment you arrived.”

I told her that I had seen Rene in the graveyard. ”I went there to look for my mother’s grave,” I explained.

“So you saw your father’s brother. Did he speak to you?”

“Yes. He was quite friendly. He was at Heloise’s grave. He knew who I was. He had heard that I was at my father’s vineyards and he recognized me. He said I was very like my mother.”

She nodded emotionally. “I wonder what he thought to see you there. I don’t suppose he told the old man. There would have been trouble if he had.”

”He really seemed more interested in my scarf than in me.”

“Your scarf?”

“Yes. I dropped it and he picked it up and saw that it was made of Sallon Silk. Then he talked about Philip. He thought he had discovered it. He was really taken aback when I told him it was Charles.”

“That family thought of little else but silk. They must have been really put out when someone other than themselves discovered the Sallon method. But something else happened?”

“Do you remember the chateau there?”

“Carsonne. Of course. Everyone knows the chateau and the de la Tours.”

“I met Gaston de la Tour.”

“The present Comte!”

I nodded. “Oh,” she said blankly.

I told her about the encounter with the dogs and our being invited to the vendange and how Katie and his son had got on so well together.

“Well, that was interesting,” she said, watching me intently.

”I met him in Paris.”

“You mean he followed you to Paris.”

“No. He was there when we were.”

“And you saw something of him.”

I nodded.

“I see. So that is it.”

“What do you mean, Grand’mere … that is it?”

“I mean he is responsible … for the change in you.”

“I do not know that there is any change.”

“You may take it from me that there is. Oh, Lenore, this is the last thing I wanted to happen. I’ve worried a lot about you. Since Philip’s death you have been lonely.”

”Lonely! With you and Katie and the Countess and Cassie?”

“I mean missing your husband.”

“I miss him, of course.”

“And this Gaston de la Tour … he seems to have made an impression on you.”

“He is quite an impressive person.”

“You are bemused by his title and his possessions … his power. …”

”I suppose they are very much a part of him.”

”You saw a great deal of him?”

”We were together every day in Paris. He took me to so many places and he is so knowledgeable about art, history and architecture that he made me see things differently.”

“Oh, Lenore … don’t you see … ?”

“Look, Grand’mere, you are worrying unnecessarily. I came back to London, didn’t I? I could have stayed in Paris. He was there.”

“I know that he is attractive and that he has a way with women. His attitude towards them is quite lighthearted. He is not good for you, Lenore. I know the family well. They have lorded it over the neighbourhood for generations. They thought they had rights to any woman they fancied. That was how they lived in the old days and Carsonne has not moved with the times.”

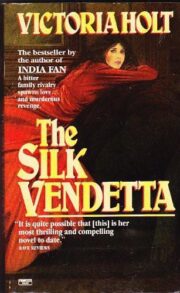

"The Silk Vendetta" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Silk Vendetta". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Silk Vendetta" друзьям в соцсетях.