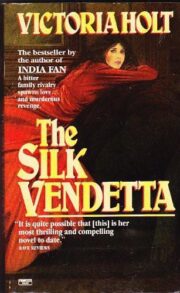

Victoria Holt

The Silk Vendetta

The Silk House

As I grew out of childhood it began to dawn on me that there was something rather mysterious about my presence in The Silk House. I did not quite belong and yet I felt a passionate attachment to the place. To me it was a source of wonder; I used to dream about all the things which had happened there and all the people who had lived in it over the centuries.

Of course, it had changed somewhat since those days. The Sallongers had changed it when Sir Francis’s ancestor bought it just over a hundred years before. He it was who had renamed it The Silk House—a most incongruous name, even though there was a reason for it. I had seen some old papers which Philip Sallonger had shown me—for he shared my interest in the house—and in these the house was named as the King’s Hunting Lodge. Which King? I wondered. Perhaps the wicked Rufus had come riding this way. It might have been William the Conqueror himself. Normans had loved their forests and revelled in their hunting. But that was probably going back in time a little too far.

There it proudly stood as though the trees had retreated to make room for it. There were gardens which must have been made in Tudor days. The walled one was evidence of this with red bricks enclosing the beds of herbs round the pond with the statue of Hermes poised over it as though ready for flight.

But the forest surrounded it and from the top windows one could see the magnificent trees—oak, beech and horse chestnut—so beautiful in the spring, so splendid in the summer, magnificent in the autumn with their variegated coloured leaves just before they fell making a carpet for our feet through which we loved to shuffle noisily; but none the less beautiful when the winter denuded them of their foliage and they made intriguing patterns against the grey and often stormy skies.

It was a big house and had been enlarged by the Sallongers when they came. They used it as a country residence. They also had a town house where Sir Francis spent most of his time and when he was not there he would be travelling through the country, for besides his headquarters in Spitalfields there were factories in Macclesfield and other parts of England. His grandfather had received his knighthood because he was one of the biggest silk manufacturers in the country and therefore an asset to society.

The ladies of the household would have preferred not to be in trade, but silk was more important to Sir Francis than anything else; and it was hoped that Charles and Philip would be the same when the time came for them to join their father in carrying on with the production of that most beautiful of all materials. So because of the family’s fervour for the product which had enriched them, and with a complete disregard for historical association, the words The Silk House had been set up over the ancient gateway in big bronze letters.

I could not remember any place but The Silk House being my home. It was a strange position in which I found myself, and it surprised me that I did not question this earlier. I suppose children take most things for granted. They have to. They know of nothing else but that by which they are surrounded.

I was there in the nursery with Charles, Philip, Julia and Cassandra who was usually known as Cassie. It did not occur to me that I was like a cuckoo in the nest. Sir Francis and Lady Sallonger were Papa and Mama to them; to me they were Sir Francis and Lady Sallonger. Then there was Nanny—the autocrat of the nursery—who would often regard me with pursed lips from which would emerge a little puffing sound which indicated a critical state of mind. I was called simply Lenore— not Miss Lenore; the others were always Miss Julia and Miss Cassie. It was apparent in the attitude of Amy the nursery maid who always served me last at meals. I had the toys which Julia and Cassie discarded although at Christmas there would be a doll or something special of my own. Miss Everton, the governess, would sometimes look at me with an expression bordering on disdain; and she seemed to resent the fact that I could learn faster than Julia or Cassie. So I should have been warned.

Clarkson, the butler, ignored me; but then he ignored the other children, too. He was a very important gentleman who ruled below stairs with Mrs. Dillon, the cook. They were the aristocrats of the servants’ hall where the observance of class distinction was more rigid than it was upstairs. Each of the servants was in a definite niche from which he or she could not emerge. Clarkson and Mrs. Dillon kept as stern a watch on protocol as I imagine would be in existence at the court of Queen Victoria. All the servants had their places at the table for meals— Clarkson at one end, Mrs. Dillon at the other. On the right hand side of Mrs. Dillon was Henry the footman. Miss Logan—Lady Sallonger’s lady’s maid, when she ate in the kitchen which she did not always do for she could have her meals taken up to her room—was on the other side of Clarkson. Grace, the parlourmaid, was next to Henry. Then there were May and Jenny, the housemaids, Amy the nursery maid and Carrie the tweeny. When Sir Francis came to The Silk House, Cobb, the coachman, joined them for meals, but he was mostly in London; and there he had his own mews cottage attached to the London home. There were several grooms but they had their quarters over the stables, which were quite extensive, for besides horses to ride, there was a gig and a dog cart. And of course Sir Francis’s carriage was housed there when he came to The Silk House.

That was below stairs; and in that no-man’s land between the upper and lower echelons of society, as though floating in limbo, was the governess, Miss Everton. I often thought she must be very lonely. She had her meals in her room—taken up grudgingly by one of the maids. Nanny, of course, ate in her own room adjoining the nursery; there she had a spirit stove on which she cooked a little, if she did not fancy the food served in the kitchen; and there always seemed to be a fire burning in the grate which had a hob for her kettle from which she brewed her many cups of tea.

I often thought about Miss Everton, particularly when I realized that I was in a similar position.

Julia was over a year older than I; the boys were several years our senior, the elder being Charles. They seemed very grand and grown up. Philip chiefly ignored us but Charles would bully us when the mood took him. Julia was inclined to be imperious; she was hot-tempered and now and then flew into uncontrollable rages. She and I quarrelled a good deal. Nanny would say: “Now Miss Julia. Now Lenore. Stop that. It’s jangling on my nerves.” Nanny was rather proud of her nerves. They always had to be considered.

Cassie was different. She was younger than either of us. I heard it said that she had given Lady Sallonger “a hard time when she came along” and that there could be no more. It was the reason for Cassie’s affliction. I had heard the servants whispering about “instruments” when they eyed her in a manner which made me think of the rack and thumbscrews of the Inquisition. They were referring to Cassie’s right leg, which had not grown as long as the left and as a result she limped. She was small and pale and pronounced “delicate.” But she was of a gentle, loving disposition and her disability had not soured her in the least. She and I loved each other dearly. We used to read and sew together. We were both adept with the needle. I think my proficiency was due to Grand’mere.

Grand’mere was the most important person in my life. She was mine—the only one in the household to whom I really belonged. She and I were apart from the rest of the household. She liked me to have meals with the other children although I should have loved to have them with her; she liked me to go with them on their riding lessons; and particularly she wanted me to study with them. Grand’mere was a part of the mystery. She was my Grand’mere and not theirs.

She lived at the very top of the house in the big room which had been built by one of the Sallongers. It had big windows and the roof even was of glass to let the light in. Grand’mere needed the light. In that room she had her loom and sewing machine and there she worked through the days. Beside the machine were the dressmaker’s dummies—like effigies of real people … three shapely ladies of various sizes, often clothed in exquisite garments. I had names for them: Emmeline was the small one, Lady Ingleby the middle size and the Duchess of Malfi was the largest. Bales of material came to the house from Spitalfields. Grand’mere used to draw the gowns first and then set about making them. I shall never forget the smell of those bales of materials. They had strange exotic names which I learned. As well as fine silks, satins and brocades there were lustrings, ala-modes, paduasoys, velvets and ducapes. I would often sit listening to the whir of the machine and watching Grand’mere’s little black slipper working at the treadle.

“Hand me those scissors, ma petite,” she would say. “Bring me the pins. Ah, what should I do without my little helper.” Then I felt happy,

“You work very hard, Grand’mere,” I said to her one day.

“I am this lucky lady,” she replied. She spoke a mixture of French and English which was different from the speech of anyone else. In the school room we did a kind of laboured French, announcing our possession of a pen or a dog or a cat and asking the way to the post office. Julia and Cassie had to struggle with it far more earnestly than I, who, because I lived so close to Grand’mere, could deliver the words with ease and a different accent from that of Miss Everton, which did not please her.

"The Silk Vendetta" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Silk Vendetta". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Silk Vendetta" друзьям в соцсетях.