“Not you personally.”

“My father and he are at daggers drawn. If they could do each other an ill turn there would be no hesitation. Why this sudden volte facet” He looked at me searchingly and I felt myself flushing. “You met him, of course.”

“Yes, in the woods. I told you.”

“I think this must be something to do with you. You will have to be careful, Lenore.”

“Don’t worry about me.”

“I think he may well be planning to pursue you. He is said to be susceptible and you are attractive.”

“He seemed to like Katie.”

“I expect that is part of the act. He apparently has little in-terest in his own son.”

“Katie was greatly taken with him. He played along with her little game of ogres and cannibalistic tendencies. He seemed amused.”

“I don’t like it. I have looked forward so much to your coming here, and now I think I shall be relieved when we return to Paris.”

“Don’t worry,” I told him. “I am not a young and innocent girl. Remember I am a widow with a child.”

“I know. But he is said to be a very attractive man.”

”I am sure he sees himself in that light.”

”I fear others do, too.”

“I tell you not to worry.”

“But you have promised to go to his vendange.”

“Katie more or less accepted before I could intervene.”

My father shook his head. “I don’t like it,” he repeated.

“All will be well,” I assured him.

And I was thinking: / did like it—although I was sure my father was right and the Comte probably thought that I should be an easy conquest.

I was greatly looking forward to proving him wrong.

That night will always stand out clearly in my memory. At the time there seemed something unreal about it. I can shut my eyes even now and recall it in every detail. The air was so clear that the stars seemed close above; it was warm and windless. The voices of the revellers came to us from a little distance away—singing to the accompaniment of violins, accordions, triangles and drums.

But most of all I remembered the Comte. He had somehow arranged that he and I should be apart from the others and we sat in a small courtyard about whose grey walls bougainvilleas bloomed and there was a smell of frangipani in the air. I sipped the special wine which he had had brought from his cellars and nibbled the cake which had been made for the occasion and which was a feature of the vendange.

From the moment he had sent his carriage to conduct Katie and me to the chateau it had been an enchanted evening. It was a somewhat cumbersome vehicle although very dignified with his family’s arms engraved on it. My father had been concerned and I had reassured him. I should be all right and Katie was with me. I said we should return at midnight and he muttered something about its being late for Katie to which I had said she might stay up for once and no harm would be done.

He was certain that the Comte was set on a course of seduction. I was largely in agreement with him, but I had no intention of becoming the easy victim of a philanderer; and I felt I had been serious too long and should be none the worse for a little light entertainment which I intended this to be.

How magnificent was the castle! It overwhelmed one with its antiquity. As we approached the platform on which it stood a feeling of anticipation swept over me. This night was going to be like no other. The high round tower of the main wing encircled by a corbelled parapet, the cylindrical towers which flanked the building, the thick massive walls, the narrow slits of windows … it all seemed to me entirely medieval. I felt that I was passing into another world.

The Comte greeted us with his son Raoul beside him. Katie and the boy eyed each other speculatively. Katie took the initiative and said: “Hello, Raoul. Do you really live here?” Then she wanted to know whether they poured boiling oil down on their enemies.

“Oh, we have more subtle means of dealing with them nowadays,” said the Comte.

As I stood in that ancient hall, I felt the past closing in on me and the Comte was an essential part of it—the overlord, the all powerful seigneur who believed that he could claim the droit de seigneur now, as his ancestors had undoubtedly done in the past.

I looked about at the weapons hanging on the walls, the great fireplace over which was displayed the arms of Carsonne, the embrasures in which there were stone benches, clearly centuries old. It was impressive indeed.

The Comte had arranged everything as he had intended it should go. He said he knew that Katie was eager to observe the manner in which they conducted the wine making at the chateau.

“Here we observe tradition,” he said. “Everything must be done as it was hundreds of years ago. You will want to see the treading.” He told Raoul that he must look after his guest. He summoned Raoul’s tutor, Monsieur Grenier, to take charge of the two of them. The housekeeper, Madame Le Grand, appeared and was presented to me. She would make sure that the children’s wine was well watered. She knew they were longing to taste the vendange cake.

So tactfully was it all arranged that Katie went off happily with them, which left me alone with the Comte.

It was an unforgettable scene.

We saw the men with their laden baskets marching to the troughs in which the grapes were to be trod to the sound of music. They must have been about three feet deep when the treaders appeared.

The Comte was watching me closely. “You are thinking this is unhygienic. Let me assure you that every precaution has been taken. All the utensils have been disinfected. The treaders’ legs and feet have been scrubbed. You see, they are in a special sort of short trousers … all of them, men and women. This is how it has always been done at the chateau. They will sing our traditional folk songs as they dance. Ah, they are beginning.”

I watched them, dancing methodically as their feet sank lower and lower into the purple juice.

“They will go on till midnight.”

“Katie …”

“Is very happy with Raoul. Grenier and Madame Le Grand will see that she is all right.”

“I think I…”

“Let us enjoy a little freedom for a while. It is good for us … even the children. Have no fear. Before midnight strikes you will be safely on your way. I give you my word. I swear it.”

I laughed. “There is no need to be so vehement. I believe you.”

“Come with me. We will escape the turmoil. I want to talk with you.”

And so I found myself in the scented courtyard on that starlit night … alone with him … and yet not alone … for we were within sound of the revelry and every now and then the night would be punctuated with a sudden shout; and there was the constant music in the background.

A servant appeared with wine and the vendange cake delicately served for us with little forks and napkins embroidered with the Carsonne crest.

“This,” he said, “is vintage chateau wine which I have served only at special occasions.”

“Such as the vendange.”

“That takes place every year. What is special about that? I meant the day when Madame Sallonger is my guest.”

“You are a very gracious host.”

“I can be charming when I am doing what I like to do.”

“I suppose we all can.”

“It is those other occasions which indicate the character and betray our faults. I want to hear about you. Are you happy?”

“As happy as most people, I daresay.”

“That is evasive. People’s contentment with life varies.”

“Happiness is rarely a permanent state. One would be very fortunate to achieve that. It comes in moments. One finds oneself saying, with a certain surprise, I am happy now.”

“Are you saying that at this moment?”

I hesitated. “I am very interested in all this. The vendange, the chateau … It is all so new to me.”

“Then can I conclude that if it is not quite happiness, it is a pleasant experience?”

“It is certainly that.”

He leaned forward. “Let us make a vow tonight.”

“A vow?”

“That we will be absolutely frank with each other. Tell me, do you feel drawn to this place?”

“I wanted to see it properly from the moment I had my first glimpse of it. You see, I was born close to here. There has always been a mystery about Villers-Mure. I am excited to be near it.”

“I was born here in this chateau. So our birthplaces are very near. Tell me, how do you feel about your grandfather?”

“Rather sad.”

“Don’t let yourself be sad on his account. I find a certain pleasure in contemplating him. I feel very strongly about him. He is the sort of person I dislike most. It is more amusing and interesting to have deep feelings about people and I am one to have such feelings. I hate or I love … and I do both most intensely.”

“It must make life rather exhausting.”

He looked at me steadily. “Your upbringing would have been very different from mine. The English are less formal than we are, I believe. Yet they cloak their feelings in assumed indifference. I call it a kind of hypocrisy.”

“Perhaps it makes life easier not to have to cope with the intense hatred and love you mention.”

He was thoughtful. “Perhaps,” he said. “I was interested to see your Katie and my Raoul together. She is quite uninhibited.”

“That is a natural characteristic.”

“As Raoul’s solemnity is with him.”

“Katie has always had absolute security. She knows she can tell me anything. I am always there to help her. I think it makes her spontaneous. It gives her confidence.”

“You mean Raoul has missed that?”

“You can tell that better than I.”

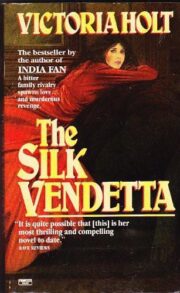

"The Silk Vendetta" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Silk Vendetta". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Silk Vendetta" друзьям в соцсетях.