“And she is happily married?”

“Yes. She has a son and a daughter. She will want to meet you. We see a great deal of each other when I go to the vineyard.”

“So that was two of you who were disowned.”

“Yes. Two of us disappointed him. My elder brother, Rene, however was a comfort to him. He is taking over a great deal of the work at the manufactory, although of course my father is still head of affairs there. Rene is a good son. And he has produced two sons … and there were two daughters … twins… . One of them, Heloise, died.”

“Long ago?”

”Twelve years or so.”

“She must have been young to die.”

“Just seventeen. She … drowned herself. It was a great blow to us all… and especially to Adele, her twin sister. They had always been close.”

“Why did she do this?”

“Some love affair. It was all rather mysterious.”

“It seems to me to be a very sad household, but then I suppose it would be with a man like your father ruling over it.”

He agreed sombrely. ”I want you to be prepared before you come.”

“I shall not think of my grandfather. If he does not wish to see me, then I have no desire to see him.”

“Ursule has expressed her eagerness to meet you. She is always urging me to bring you.”

“Then I shall look forward to meeting her. She is, of course, my aunt.”

“You will like her, and Louis Sagon. He is immersed in his work and appears to have little interest in anything else, but you will like him. He is a quiet, gentle, kindly man.”

”I shall be content with meeting them—and forget all about my ogre of a grandfather.”

In spite of the fact that he had prepared me in a way for what I must expect, my father seemed to view the proposed visit with some trepidation.

I said goodbye to Grand’mere and the Countess, and Katie and I set off with my father.

We travelled by train and it was a long journey from Paris. Katie was in a state of high excitement. She kept to the window, my father beside her, pointing out the landmarks as we went along. We passed through towns and farmlands, past rivers and hills. There was great interest when we saw vineyards and my father would cast a knowledgeable eye over them; we glimpsed several ancient castles—grey-stoned with the pepper-pot towers which were such a feature of the country. My father was growing a little subdued as we drew nearer and nearer to his birthplace. I fancied he was suffering a certain uneasiness and I wondered whether he was asking himself whether his father would hear of my presence and what his reaction would be.

They were to send a carriage to the station of Carsonne to take us to the house. He told me that they would know exactly when we should arrive as there was only one train a day.

It was a small station.

”We are lucky to have it,” he said. ”The Comte de Carsonne insisted on it. He is a very influential man. It was something of a fight, I believe, but the Comte usually gets his way in such matters.”

As we came into the station my father waved his hand towards a man in dark blue livery who was standing there.

“Alfredo!” he called. He turned to me. “He is Italian. Some of the servants are. We are very close to the borders and that makes us somewhat Italianate in certain ways.”

Alfredo was at the door taking the luggage.

“This is my daughter, Madame Sallonger,” said my father, “and my granddaughter, Mademoiselle Katie Sallonger.”

Alfredo bowed. We smiled at him and he took our bags.

My father was evidently a man of some importance in the neighbourhood if the respect which was shown him was any indication. Caps were touched and welcomes offered.

Then we were in the carriage driving along.

The vineyard was spread out before us. People were already gathering the grapes and we saw the labourers with their oziers, so carefully poised as not to damage the grapes with too much motion.

My father said: “We are in good time for the vendange. “At which Katie expressed her pleasure.

Ahead I saw the chateau. It stood on what looked like a square platform surrounded by deep dykes.

“How grand!” I exclaimed.

“Chateau Carsonne,” said my father.

“And does this Comte … the one who insisted on bringing the railway to Carsonne … live here?”

“The very same.”

“Does he actually reside there?”

“Oh yes. I believe he has a house in Paris … and probably in other places, but this is the ancestral home of the Carsonnes.”

“Shall we meet them, these Carsonnes?”

“It is hardly likely. Our families are not on the best of terms.”

“Is there some sort of feud?”

“Hardly that. My father’s land borders on theirs. There is a sort of armed neutrality … not open warfare … but both sides ready to go into action at the least offence from the other.”

“It sounds very warlike to me.”

“It is hard for you with your English upbringing to understand the fierce nature of the people here. It is the Latin blood … and although you were born with it, your upbringing has evidently brought down its boiling point.”

I laughed. “It all sounds very interesting.”

“We shall soon see my place. Oh, look. Ahead of you.”

Katie leaped up and down with excitement. My father put an arm about her and held her against him.

It was like a miniature chateau with the now familiar pepper-pot towers. It was of grey stone and there were green shutters at the windows, several of which had wrought-iron balconies. It was charming.

As we drew up I saw a man and a woman standing at the door as though to receive us.

“There is Ursule,” said my father. “Ursule, my dear, how good of you to come over to greet us. And you, Louis.” He turned to me. ”This is your aunt Ursule. And this is her husband Louis.” He smiled at them. “Lenore,” he said, “and her daughter, Katie.”

“Welcome to Carsonne,” said Ursule. She was dark-haired and not unlike my father. There was an air of kindliness about her and I liked her immediately. Louis was, as my father had said, a very gentle man. He took my hands and said how pleased he was to see me.

”We have been urging your father for a long time to bring you here,” said Ursule. “Come along in. We live half a mile away. I had to come over to welcome you.”

We went into the house and were in a long panelled hall with a great fireplace round which gleamed brass ornaments.

“I have arranged which room Lenore shall have,” said Ursule. ‘ ‘I thought it better not to leave it to the servants, and Katie shall have the one immediately next to hers.”

“That is thoughtful of you,” I said. “We like to be close.”

Katie was taking everything in as Ursule took us up to our rooms. Mine was low-ceilinged with pale green drapes and bedspread and there were hints of green in the light grey carpet. It was a charming restful room and what delighted me was the communicating door between it and Katie’s.

In mine there was a balcony. I opened the french windows and stepped out. In the distance I could see the towers of the Chateau Carsonne and the terracotta coloured roofs of the houses in the little town close by. And there below me were the ever-present vines.

I felt touched in some odd way. Beyond the chateau lay Villers-Mure—the mulberries and the manufactory … the place where I had first seen the light of day. I suppose one must be moved by the sight of one’s birthplace, particularly when one has never seen it before.

Hot water was brought and we washed and changed our clothes. Katie kept exclaiming at something new she had discovered.

She said: “Isn’t it exciting to find a grandfather in the park? You’re always finding out something about him. Other people’s grandfathers are rather dull. They’ve been there all the time.”

“Some people might like it that way,” I commented.

“I don’t. I like it our way.”

After we had eaten a meal in the courtyard we were taken back into the house to meet the servants. There were quite a number of them. Ursule explained everything to me as we went along.

“We eat in the courtyard until it gets too cold. We like the fresh air. And it can be very hot sometimes. Georges—your father’s son … your half-brother really … comes here quite frequently. He has his own place now about fifteen kilometres away. His sister Brigitte has recently married and lives in Lyons. I daresay you’ll meet them sometimes. I am so glad you and my brother are together. He has never forgotten your existence and when your grandmother came here and sought him out he was so excited … so happy. So it is wonderful to see you here.”

“He has been so good to me.”

“He feels he can never make up.”

“He has to me … more than I can say.”

She asked if I could ride and I told her that I could.

”That is good. It is not easy to get around any other way and you should see a little of the countryside.”

“I should like to see Villers-Mure.”

She did not speak for a moment. Then she said: “I haven’t been there for over twenty years.”

“Yet it is so near.”

“Did you know the story? I displeased my father when I married. It is not forgotten.”

“It seems … terrible … all that time.”

“That’s the way it is.”

“Have you never tried to become friendly again?”

“It is clear that you do not know my father. He is a man who prides himself on keeping his word. He has said he will never see me again—and that is what he will do.”

“He must miss a great deal in life. He must be very unhappy. ”

She shook her head. “He has what he wants. He is the Seigneur of Villers-Mure. He is the king in his domain and all must obey him or suffer the penalty he inflicts upon them for disobedience. I believe he is content. Well, I have never regretted choosing the way I did.”

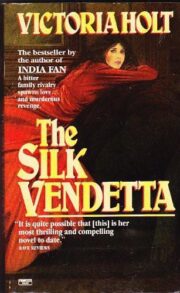

"The Silk Vendetta" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Silk Vendetta". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Silk Vendetta" друзьям в соцсетях.