With Mademoiselle she would take her hoop into the gardens; they would ride in steamers along the Seine; she would make the acquaintance of other children there and was soon able to chat with them. With Miss Price she took quiet walks along the river, looking at the books on the stalls and visiting places of historic interest. Miss Price made a point of studying the history connected with the places they visited and afterwards Katie would pass on what she had learned to me and I was pleased and gratified by the knowledge she was acquiring.

There were a few initial difficulties to be smoothed out, but the Countess was adept at dealing with such matters and sooner than I had expected we were establishing ourselves.

I thought of home. In the election which had taken place soon after Drake’s wedding Gladstone had triumphed though without the large majority for which he had hoped and—much to the Queen’s disgust—went to Osborne to kiss her hand. “A deluded old man of eighty-two,” she called him, “trying to govern England with his miserable democrats. He was quite ridiculous.”

“This will be a step up for a certain party,” commented the Countess.

I wondered what he was doing. Whether he was finding Julia’s social expertise a compensation for a lack of love.

“But they’ll be out soon,” said the Countess. “It’s Gladstone’s obsession with Ireland that will be their downfall.”

I used to wonder a great deal about the child who had been so casually conceived. I wondered whether it would prove a consolation to Drake. It was some time before I heard that there had never been a child—so the very reason why Drake had married Julia had not existed.

I longed for news. I was thinking of Drake a good deal. I heard that Gladstone’s Home Rule Bill though it had passed through the Commons had been rejected by the Lords.

Another year passed and I was still thinking of Drake. We were so busy that there was time for little else beside the salon.

My father paid periodic visits to Paris. He was a great help to us—not only financially—for he was as eager as any of us to see the business a success.

Katie was a delight to him—especially when she could chatter in his own language. He was constantly urging me to visit his vineyards. Katie would love it, he said. And how right he was.

He had several but his favourite was the one in Villers-Carsonne, which was very close to Villers-Mure. I had an idea that this was the one he loved best because it was close to his old home and the country was the scene of his childhood. His voice softened when he spoke of it; but it was not to it that he took us first, but to one not so far from Paris.

He thought Katie would be interested in the vendange. In fact, she was quite enchanted, and she thoroughly enjoyed those weeks we spent there. She was learning to ride. My father set one of the grooms to teach her and when she was not joining in the harvesting of the grapes, she was riding with the groom. My memory went back to those days when she had ridden round the paddock at Swaddingham with Drake and I was sad watching and thinking of what might have been.

Her happy face was some consolation to me. It was a great occasion when she was let off the leading rein. My father said she was a born horsewoman and as much at home on a horse’s back as on her own two feet. He would ride with her round the vineyard—he on his big black horse, she on her pony while he told her about the grapes, answering her interminable questions with pleasure; and afterwards she would come and tell me everything.

This was one of the more old-fashioned of his vineyards and here they trod the grapes in the ancient manner. I think he had wanted Katie to see this and it was his reason for bringing us here.

He would talk to her as though she were an adult—which won her heart—explaining to her that at most of his vineyards he used a machine to crush the grapes. It had two wooden cylinders turning in opposite directions and in this machine not a single grape escaped. But some liked the old ways best and preferred to do what had been done through the centuries.

What a night that was! The grapes, which had been laid out for ten days on a level floor to take the sun, were put into troughs, and the villagers sang as they danced on them, crushing them while the juice trickled through into the vats which had been placed below to catch it.

It was magic to Katie, and perhaps to all of us. My father’s eyes were sentimental as he watched her—her hair flying loose, her eyes alight with excitement.

“You must always come to the vendange,” he said.

Katie was reluctant to return to Paris, but soon she forgot the regrets and was content again.

I remember the day when one of our English clients came to Paris. She was Lady Bonner, a noted hostess, who was said to know more of other people’s private lives than any other woman in London. She was voluble and always eager to impart the latest scandal.

She knew of my connection with Julia and asked if I had heard from her lately.

I said that we had not.

“Oh dear me! Quite a scandal. Poor Drake, what a mistake he has made! Of course, it was her money. He needed that. He is an ambitious man. Mind you, he comes from a wealthy family, but he has that sort of pride that says No, I will make my way on my own. Making his way meant marrying money … and so he did that. But what a burden the poor man found he had taken on. She drinks … you know.”

All I said was: “Oh?”

“Oh yes, my dear. Surely you knew. It was always a problem with her and now it has become really serious.”

“There was to be a child …” I began. “Perhaps having lost it…”

“A child! Good Heavens, no! That’s not Julia’s line at all. It was this function. She was so intoxicated… . She staggered when she was talking to Lord Rosebery … and if Drake hadn’t been there to catch her, she would have fallen flat on her face. You can imagine the talk. Poor Drake was overcome with embarrassment. This could cost him a post in the government… if there ever is a stable one. He thought her money would help … and so it would if she had been the right sort of wife. They all think they are going to get a Mary Anne Disraeli. He made a big mistake, poor man, and it may well cost him his career.”

“But he is an able politician,” I protested.

“Only half of the battle, my dear.”

She went on talking of the London scene but I was only half listening. I was thinking of Drake who had blundered into such a disaster.

Poor Drake, he was no happier than I was—in fact he had not the consolations which I was so grateful for.

Cassie came to Paris now and then and often the Countess went to London. We were now making a profit in Paris and business was flourishing in London where our name had been greatly enhanced. We were a big name in the world of fashion.

Three years had passed since Drake’s marriage to Julia and Katie was now eleven years old.

One day my father said: “I am going to take you to Villers-Carsonne.”

He had often seemed a little secretive when he mentioned it and I had the feeling that there was some reason why he was not eager to talk of the place, let alone take us there.

Now he seemed to have come to the conclusion that the time was ripe. He sought an opportunity, when we were alone, to talk to me.

“You may have wondered,” he said, “why I have not suggested you come to Villers-Carsonne before.”

I admitted that I had.

“It is near the place where I was brought up. It is my favourite vineyard. There we produce our best wines. I am there frequently, but I have never taken you there. Why? you asked.”

“I did not,” I said, “but I will.”

He hesitated for a while and then he said: “This is because I have much to tell you. Your grandfather, Alphonse St. Allen-gere, is well known throughout that part of the country. They say that he is Villers-Mure. It may be difficult for you to understand but Villers-Mure resembles a feudal community. In Villers-Mure my father is the lord of all, the grand seigneur. Monsieur le Patron. He is as powerful as a medieval king. It is a restricted community. Almost everyone depends on the silk manufactory; he owns that manufactory; and therefore they owe their livelihoods to him.”

”He sounds formidable.”

He nodded gravely. “He would not receive you, Lenore.”

“I realize that he does not accept me as his granddaughter. But should that prevent my going to your vineyard? That does not belong to him, does it?”

“It is mine. He does see me when I am there. Because I have done well and not through his help he has a certain respect for me. I am an undutiful son, he implies, but grudgingly, he allows me to call on him.”

”I think I should be inclined to refrain from calling.”

“One does not. He has a certain quality … and as much as one resents his attitude one finds oneself obeying.”

“I am quite prepared not to be received.”

“My sister Ursule will be delighted to meet you.”

”Will she be allowed to? “

“Ursule does not live at the house in Villers-Mure. She lives in Villers-Carsonne. She was disowned long ago. She defied him, you see.”

“Forgive me, mon pere, but your father seems to be a man it is better not to have to meet.”

He nodded. “Ursule was disowned shortly after I was. Louis Sagon, her husband now, came to the house to restore my father’s pictures. He painted a portrait of Ursule and fell in love with her—and she with him. My father had other plans for her. He forbade the match. They eloped and as a result she was cut off from the house. She married Louis Sagon and they settled in Villers-Carsonne. My father has never seen her since. She was more courageous than I was.”

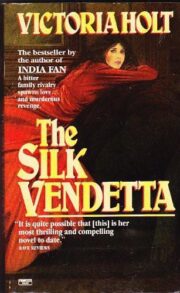

"The Silk Vendetta" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Silk Vendetta". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Silk Vendetta" друзьям в соцсетях.