I wondered a great deal about my father. Sometimes I thought it was rather romantic not to know who one’s father was. One could imagine someone who was more exciting and handsome than real people were. One day, I told myself, I will go and find him. That started me off on a new type of daydream. I had a good many imaginary fathers after that talk with Grand’mere. Naturally I could not expect to be treated like Miss Julia or Miss Cassie, but how dull their lives were compared with mine. They had not been born to the most beautiful girl in the world; they did not possess a mysterious, anonymous father.

I realized that we were, in a way, servants of the house.

Grand’mere was of a higher grade—perhaps in the same category as Clarkson or at least Mrs. Dillon—but a servant none the less; she was highly prized because of her skills and I was there because of her. So … I accepted my lot.

It was true that Lady Sallonger was demanding. I was expected to be a maid to her. She was really beautiful—or had been in her youth and the signs remained. She would lie on the sofa in the drawing room every day, always beautifully dressed in a be-ribboned negligee and Miss Logan had to spend lots of t ime doing her hair and helping her dress. Then she would make her slow progress to the drawing room from her bedroom leaning heavily on Clarkson’s arm while Henry carried her embroidery bag and prepared to give further assistance should it be needed. She often called on me to read to her. She seemed to like to keep me busy. She was always gentle and spoke in a tired voice which seemed to have a reproach in it—against fate, I supposed, which had given her a bad time with Cassie and made an invalid of her.

It would be: “Lenore, bring me a cushion. Oh, that’s better. Sit there, will you, child? Please put the rug over my feet. They are getting chilly. Ring the bell. I want more coal on the fire. Bring me my embroidery. Oh dear, I think that is a wrong stitch. You can undo that. Perhaps you can put it right. I do hate going back over things. But do it later. Read to me now …”

She would keep me reading for what seemed like hours. She often dozed and thinking she was asleep I would stop reading, and then be reprimanded and told to go on. She liked the works of Mrs. Henry Wood. I remember The Channings and Mrs. Halliburton’s Troubles as well as East Lynne. All these I read aloud to her. She said I had a more soothing voice than Miss Logan’s.

And all the time I was doing these tasks I was thinking of how much we owed these Sallongers who had allowed us to come here and escape my mother’s shame. It was really like something out of Mrs. Henry Wood’s books, and I was naturally thrilled to be at the centre of such a drama.

Perhaps being in a humble position makes one more considerate of others. Cassie had always been my friend; Julia was too haughty, too condescending to be a real friend. Cassie was different. She looked to me for help and to one of my nature that was very endearing. I liked to have authority. I liked to look after people. I realized my feelings were not entirely altruistic. I liked the feeling of importance which came to me when I was assisting others, so I used to help Cassie with her lessons. When we went walking I made my pace fit hers while Julia and Miss Everton strode on. When we rode I kept my eye on her. She repaid me with a kind of silent adoration which gave me great satisfaction.

It was accepted in the household that I look after Cassie in the same way as I was expected to wait on Lady Sallonger.

There was one other who aroused pity in me. That was Willie. He was what Mrs. Dillon called “Minnie Wardle’s leftover.” Minnie Wardle had, by all accounts, been “a flighty piece,” “no better than she ought to be,” who had reaped her just reward and “got her comeuppance” in the form of Willie.

The child was the result of her friendship with a horse dealer who had hung round the place until Minnie was pregnant and then disappeared, Minnie Wardle thought she knew how to handle such a situation and visited the wise old woman who lived in a hut in the forest about a mile or so from The Silk House. But this time she was not clever enough, for it did not work; and when Willie was born—again quoting Mrs. Dillon—he was “tuppence short.” Her ladyship had not wanted to turn the girl out and had let her stay on, Willie with her; but before the child was a year old, the horse dealer came back and Minnie disappeared with him, leaving behind the wages of her sin to be shouldered by someone else. The child was sent to the stables to be brought up by Mrs. Carter, wife of the head groom. She had been trying to have children for some time and not being able to get one was glad to take someone else’s. But no sooner did she take in Willie than she started to breed and now had six of her own and was not very interested in Willie—particularly as he was “a screw loose.”

Poor Willie—he belonged to no one really; no one cared about him. I often thought he was not so stupid as he seemed. He could not read or write, but then there were many of them who could not do that. He had a mongrel which followed him everywhere and was known by Mrs. Dillon as “that dratted dog.” I was glad to see the boy with something which loved him and on whom he could shower affection. He seemed brighter after he acquired the dog. He liked to sit with the dog beside him looking into the lake, which was in the forest not very far from The Silk House. One came upon it unexpectedly. There was a clearing in the trees and then suddenly one saw this expanse of water. Children fished in it. One would see them with their little jars beside them and hear them shrieking with glee when they found a tadpole. Willows trailed in the water and loosestrife with its star-like blossoms grew side by side, with the flowers we called skull-caps, among the ubiquitous woundwort. I never failed to wonder at the marvels of the forest. It was full of surprises. One could ride through the trees and suddenly come upon a cluster of houses, a little hamlet or a village green. At one time the trees must have been cut down to make these habitations, but so long ago that no one remembered when.

The years had changed the forest but only a little. At the time| of the Norman Conquest it must have covered almost the whole of Essex; but now there were the occasional big houses and the old villages, the churches, the dame schools, and several little hamlets.

It was not easy to communicate with Willie. If one spoke to him he looked like a startled deer; he would stand still, as though poised for flight. He did not trust anyone.

It is strange how some people enjoy baiting the weak. Is it because they wish to call attention to their own strength? Mrs. Dillon was one of these. She it was who had stressed the fact that I was not of the same standing as my companions. It seemed to me now that instead of trying to help Willie she called attention to his deficiencies.

Naturally he was expected to help about the house. He brought water in from the well; he cleaned the yard; and these things he did happily enough; they were a habit. One day Mrs. Dillon said: “Go to the storeroom, Willie, and bring me one of my jars of plums. And tell me how many jars are left.”

She wanted Willie to come back plumless with a look of bewilderment on his face so that she could ask God or any of His angels who happened to be listening what she had done to be burdened with such an idiot.

Willie was nonplussed. He could not know how many were left; he could not be sure of picking out plums. This gave me a chance. I beckoned him and went with him to the storeroom. I picked out the plums and held up six fingers. He stared at me and again I held up my fingers; at last a smile broke out on his face.

He returned to the kitchen. I think Mrs. Dillon was disappointed that he had brought what she had asked for. “Well,” she demanded, “how many’s left?” I hovered in the doorway and behind Mrs. Dillon’s back I held up six fingers. Willie did the same.

“Six,” cried Mrs. Dillon. “As few as that. My goodness, what have I done to be given such an idiot.”

” It’s all right, Mrs. Dillon,” I said. ”I went and had a look.

There are six left.”

“Oh, it’s you, Lenore. Poking your nose in as usual.”

“Well, Mrs. Dillon. I thought you wanted to know.” I walked out of the kitchen, I hoped, with dignity. I passed Willie’s little dog who was sitting patiently waiting for his master.

Whenever I could I would try to help Willie. I often found him giving me a sidelong glance, but he hastily averted his eyes if I caught him at this.

I wished I could help him more. It occurred to me that it might be possible to teach him a little, for he was not so stupid as people thought.

I used to talk about him to Cassie, who was very easily moved to pity, and she would try to do little things for him, such as showing him which were the best cabbages to pull from the kitchen garden when he was sent out for this purpose by Mrs. Dillon.

I was very interested in people’s behaviour and I wondered why Mrs. Dillon, who was comfortably placed herself, should be so eager to make the life of someone like Willie more of a burden than it already was. Willie was a frightened boy. As I said to Cassie: “If he could only get rid of that fear of people, he would take a step towards normality.”

Cassie agreed with me. She invariably did. Perhaps that was why I liked being with her so much.

Mrs. Dillon was relentless. She said that Willie should be “put away” because it wasn’t what was to be expected in a place like The Silk House to have idiots roaming about. When Sir Francis came she would speak to him on the subject. It was no use saying anything to her ladyship and Mr. Clarkson had no authority to get him sent away.

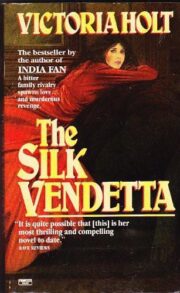

"The Silk Vendetta" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Silk Vendetta". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Silk Vendetta" друзьям в соцсетях.