“He has hidden talents no doubt,” I said.

“He has never displayed them before. Even when we were there he seemed almost indifferent.”

“Well, it shows how mistaken one can be.”

“I should love to go back,” said Philip. “I want to visit some of the Italian towns. I did see one or two of them briefly. Rome … Venice … and Florence. It was Florence which caught my fancy. It was so wonderful to go out to the heights of Fiesole and look over the city. I shall go back there one day.” He was smiling at me. “You would enjoy it, Lenore,” he added.

I was happy. He looked at me so lovingly and I had never seen Grand’mere so happy. I knew it was because of Philip’s desire to marry me.

There was magic in that evening … sitting there with Grand’mere, dreams in her eyes, and Cassie looking so pleased with us all. Grand’mere and Philip exchanged glances as though there was some delightful conspiracy between them.

I wanted the night to go on and on. It was wonderful to be seventeen and no longer a child. Philip took my hand and pressed it. There was a question in his eyes.

Grand’mere was waiting, holding her breath, her lips moving as I had seen them do in silent prayer.

“Lenore,” said Philip, “you will, won’t you?”

And I said Yes.

What rejoicing there was!

Philip took the ring and put it on my finger. Grand’mere wept a little—but, she assured us, with pure happiness.

“It is my dearest dream come true.”

Cassie hugged me. “You’ll be a real sister now,” she said.

Grand’mere poured champagne into glasses and Philip put his arms about me and held me tightly while Grand’mere and Cassie raised their glasses to us.

“May the good God bless you,” said Grand’mere, “now … and always.”

The news of our engagement was received in various ways by members of the household. Lady Sallonger was at first inclined to be shocked. I knew exactly how her mind worked and she always considered every situation as to what effect it would have on her. Her first reaction was that Philip should have looked higher. It was hardly seemly that his choice should have fallen on one who was, in her mind, rather like a higher servant. Madame Cleremont, it was true, was in a rather special position and she had made certain demands which had been accepted when she came, but she was only a servant after all. Lady Sallonger was rather peevish. It was too much to present her with such a situation when poor Sir Francis had passed on and left heavy responsibilities on her shoulders. She was really too exhausted to deal with matters like this. People should have more consideration. Then she began to change her mind a little. I should be a daughter-in-law. I should be grateful to have risen to such a position in the household. She could make even more demands on my company; and I was useful to her. So perhaps it was not such a bad thing after all. At least it might have its compensations—and Philip was after all a younger son.

Julia was put out. It was galling to think of all she had gone through without having received one proposal yet, and without any help, on my seventeenth birthday I was engaged. Everyone would say that, in my position, it was as good a match as I could possibly make. So I had done well for myself and scored over Julia.

As for the servants they were dismayed. They did not care that someone who had occupied a minor position in the house should come to one of importance which would naturally fall to the wife of one of the sons. It was like the governess’s marrying the master of the house, which had been known to happen now and then.

“It was all wrong,” said Mrs. Dillon. “It was going against the laws of nature.”

Cassie, of course, was delighted.

When Julia came home to stay for a weekend at The Silk House to see her mother, she was accompanied by the Countess of Ballader. That lady took me aside. She seemed genuinely pleased. “Well done,” she said, with such approval that one would have thought that the whole purpose of a girl’s existence was to get a husband. “I said from the start that I wished it had been you I had to handle.”

Julia was cool to me during that weekend, and I was glad when she and the Countess left.

Then there was Charles. His attitude since Drake Aldringham had shown his contempt for him had been one of studied indifference. It was always as though he were unaware of my existence. He gave an amused smile when he was told of the engagement as though it were something of a joke.

Philip was as excited about the wedding as he had been about Sallon Silk. There was something single-minded about Philip; when a project lay ahead he was all enthusiasm to complete it. I liked that in him. In fact there was a great deal I liked about Philip. I believed I loved him, though I was not sure. I liked to be with him; I liked to talk to him; and best of all I liked the manner in which he treated me—as though I was very precious and he was going to spend his life looking after me.

Our wedding was to be in April. That gave us five months to prepare.

“There is absolutely no sense in waiting,” said Philip.

Grand’mere had long conversations with him. She talked at great length about “settlements.” I was appalled when I understood what she meant.

“Are you suggesting that Philip should make some payment?” I asked incredulously.

“It is done in France. There people face these facts. On the day you marry Philip he will settle a certain sum upon you and that money is yours … in case anything happens to him.”

” Happens to him?”

“Ah, mon enfant, one never knows. One cannot be too careful. There is an accident… and what is a poor widow to do? Is she to be thrown on the mercy of her husband’s family?”

“It is all so sordid.”

“You must bring a practical mind to these matters. It will not concern you. It will be arranged with the lawyers and Philip and me … for am I not your guardian?”

“Oh, Grand’mere,” I said, “I wish you wouldn’t. I don’t want Philip to have to pay money.”

”It is just a settlement… nothing more. It means that once you are married to him you are safe … secure …”

“But I am not marrying him for that!”

“You are not … but there are those who must watch for your rights. We have to be practical and this is a matter for your guardian and not for you.”

When I was alone with Philip I broached the matter with him.

He said: “Your grandmother is an astute business woman. She knows what she is about. She wants the best for you … and as I do, we are of one mind.”

“But all this talk of settlements is so mercenary.”

“It seems so, but it is the right thing to do. Don’t think about it. Your grandmother shall have what she wants for you. I thought Italy for our honeymoon. When I was in Florence I thought of you often. I kept saying to myself: I must show Lenore that, so this is exactly what I am going to do. So agree that it shall be Florence.”

“You are so good to me, Philip,” I said emotionally.

“That is what I intend to be … always, and you will be good to me. Ours will be the perfect marriage.”

“I hope that I shan’t disappoint you.”

“What nonsense! As if you could! So it is to be Florence then. It is so beautiful. It is the home of the greatest artists in the world. You sense it as you walk through those streets. We’ll go to the opera. That should be a splendid occasion. You shall have a beautiful gown of Sallon Silk. Your grandmother must make it. A special one for the opera.”

I laughed and said: “And you shall have a long black opera cloak and an opera hat … one of those which collapse and spring up and look so splendid.”

“And we shall walk through the streets to our albergo. We shall have a room with a balcony … perhaps overlooking a square and we shall think of the great Florentines who have worked in this unique city and given the world its greatest art.”

“It is going to be wonderful,” I said.

The weeks sped by. I was so happy. I knew that Grand’mere was right. This was the best thing that could have happened to me. Philip was in London a great deal. He was going to take three weeks’ holiday which should be our honeymoon. He could not make it longer.

Then we should come back to The Silk House for a while and later go to London. The house there was used jointly by Charles and Philip. Philip thought that later on we must have a place of our own. I thought so, too. The idea of Charles sharing our home was distasteful to me. I did not trust him. I never should again; and although he seemed to wish to forget that incident in the mausoleum, I could not entirely do so.

Grand’mere was blissfully busy making gowns for me. There was my wedding gown of white satin and Honiton lace. It was far too grand for the simple wedding we planned. But Grand’mere insisted on making it her way. Then there was my trousseau. She had listened to our talk of the honeymoon and how we planned to go to the Italian opera. She made me a dress of blue Sallon Silk and a black velvet cloak to go with it. When Philip came home from London, I wanted him to see it. He came up with something under his arm and when I stood before him in my Sallon Silk gown he unfurled a black cloak and put it on. Then he produced the opera hat.

We laughed. We paraded, arm-in-arm, round Grand’mere’s workroom singing La Traviata. Cassie clasped her hands with glee and Grand’mere watched, happier than I had ever known her before. I guessed she was thinking how different my story was from my mother’s.

It was to be a simple wedding. We both wanted that. There would be very few guests and soon after the ceremony we were to set out on our honeymoon.

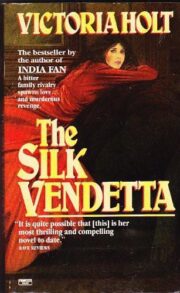

"The Silk Vendetta" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Silk Vendetta". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Silk Vendetta" друзьям в соцсетях.