In due course Easter was with us and Julia was delivered by Miss Everton into the hands of the Countess and the real process had begun.

The workroom was very quiet. Cassie said Emmeline was sulking. Grand’mere made two dresses—one for Cassie and one for me—out of the material left over from Julia’s needs. We called them our coming out dresses.

August came and the season was drawing to an end. No dukes, viscounts, baronets or even a simple knight had asked for Julia’s hand. She was to come down to Epping for a few weeks’ rest after her strenuous time, and then she would go up to London again, and under the excellent guidance of the Countess of Bal-lader make a fresh onslaught onto London society.

Philip and Charles had returned from France. Philip came to the house occasionally. He spent a lot of time in the big work- room. I would be there often with Cassie and he would talk enthusiastically about what he had seen in France.

He was worried about his father’s health. Sir Francis would insist on going to Spitalfields and he did tire easily. Philip thought he should rest more—something which Sir Francis refused to do.

There was a great deal of excitement in London for Charles had produced some fantastic ideas which had been of inestimable value to those who were researching on new methods.

“Charles of all people,” marvelled Philip. ”Who would have thought he was interested enough? He has contrived some formula. He said he has been working it out for some time. So odd. He gave no sign. I should never have thought he was such a secretive fellow. … To keep something like that to himself! At first I was inclined to be skeptical … but it seems it is just the climax to something our people have been working on for years. I’m having a special loom made, Madame Cleremont, and I’m going to bring it up here to you, but this has to be secret until it is launched. I don’t want any rivals to get a whisper of it. It is going to produce a certain weave which will bring a special sheen … not seen before. I think it is going to produce something quite different from anything we have done before. And to think that the clue to this perfection has come through Charles!”

The new loom arrived and Grand’mere used to talk to me about it every night when we were alone.

“Philip is so excited,” she said. “I think we shall soon have perfected it. Who would have believed it of Charles! And the funny thing is now that he has given us the key which is bringing it to perfection he seems to have lost interest. Philip is most excited. I think we’ll have made it in a few days now. We shall have to make sure it remains Sallongers’.”

“There is that patent Philip mentioned at the Crown and Sceptre.”

“That’s right.”

Philip had been at The Silk House for about two weeks. He was caught up in the excitement.

“This could be something quite unique,” he kept declaring.

Then came the great day. Philip took the piece of silk material which Grand’mere handed to him and they looked at each other with shining eyes.

“Eureka!” shouted Philip.

He seized Grand’mere and hugged her. Then he turned to me, lifted me up and swung me round. He kissed me heartily on the lips.

“This is going to be the turn of the tide,” he said. “We will celebrate.”

“At the Crown and Sceptre,” said Grand’mere, “with whitebait and champagne.”

Cassie came in. She stared at us in amazement.

“It’s a great occasion, Cassie,” I cried. “That which has been sought has been found.

“Cassie must join us in the celebration,” I added.

Philip took the material and kissed it reverently. “This is going to bring success to the Sallongers,” he said.

“Don’t forget the patent,” I reminded him.

“Wise girl,” he cried. “I shall see to it this very day. We need a name for it.”

Grand’mere said: “Why not Lenore Silk? Lenore has had a hand in it.”

“No, no,” I cried. “That would be ridiculous. It is Charles’s really and yours, Philip … Grand’mere’s too. I have just stood by and done the fetching and carrying. Let’s call it Sallon Silk. That’s part of the family name and we have alliteration’s artful aid.”

On consideration it was decided that that was a good name. And that evening we sailed to Greenwich and, as Grand’mere had suggested, celebrated on whitebait and champagne.

For some time we talked of little but Sallon Silk. It was an instant success and there were articles about it in the papers. Sallongers were commended for their enterprise and the prosperity they were bringing to the country. ”There is no silk which can match its excellence,” said the fashion editors. “Nothing from China or India, Italy or even France can compare with it. Sallon is unique and we should be proud that it has been discovered by a British company.”

We used to talk about Sallon when we were in Grand’mere’s workroom. Philip was often there discussing new ways of turning the invention to advantage. At the moment it was very expensive and a Sallon Silk dress was an essential of every fashionable wardrobe; but Philip wanted to use the method for producing cheaper material and so putting it within the reach of many more women to possess a Sallon Silk dress.

It was now being made in the factories. New looms had been installed for the purpose and Grand’mere, to her delight, was experimenting with an idea to bring out a cheap version.

She, Cassie and I were caught up in the project. Julia was in London where the Countess had moved into the house in Grantham Square and she was chaperoning Julia on her engagements.

We were into another year. I should soon be seventeen. Grand’mere had always implied that that was an age when wonderful things would happen.

Then the blow fell. Sir Francis had another stroke and this time it was fatal.

It was a bleak January day when they brought his body to Epping for burial. The coffin lay in the house for two days before it was taken to the mausoleum. There was to be a service in the nearby church and then Sir Francis would be brought to his last resting place.

The whole family was assembled at the house. Lady Sallon-ger assumed great grief which I felt could not be genuine for she had seen so little of him and never seemed to miss him. She insisted on going to the service to see the last she said of “dear Francis.” She was carried down to the carriage, looking frail in her black garments and hat with the sweeping black ostrich feathers. She held a white handkerchief to her eyes and insisted that Charles should support her on one side and Philip on the other.

It was chilly in the church. The coffin stood on trestles throughout the service, then it was taken to the carriage and we made our slow ceremonial way to the mausoleum.

Standing there in the bitter wind memories came back to me. Several of the servants were there and I noticed Willie with the dog in his arms.

On the edge of the crowd was a stranger. She was dressed in black and there was a veil over her face. She looked tragic.

I knew at once who she was and I saw that Grand’mere did too.

“Poor woman,” she whispered.

It was Mrs. Darcy.

The summer had come. Philip was often at The Silk House. Grand’mere used to grow pink with pleasure when she heard his voice. He talked to us about the business.

“There is no doubt,” he said, “that the discovery of Sallon Silk has saved us from bankruptcy. Yes,” he continued, ”things were pretty bad. No wonder my father worried himself into an illness. The French were getting the better of us at every turn. They could produce so much cheaper and I suspect that they were cutting their prices just to wipe us out of the market. Well, we’ve retaliated. Sallon Silk has saved us.”

“Charles must be very proud.”

“He’s not in the office much. He says he’ll come when he’s found some other invention which will revolutionise the silk industry.”

“How very strange,” I said, “that he, who is not really interested—or doesn’t appear to be—should come up with this miraculous discovery.”

“Odd indeed. I begin to think he must have a big feeling for silk after all. He is now having what he calls a good time. I have to say he deserves it and as long as he is ready to settle down in time, we’ll let him continue.”

Now that I was approaching my seventeenth birthday it seemed that I should be out of the schoolroom. I should have liked to work more with Grand’mere. I was getting more and more immersed into the excitement of the new discovery and 1 loved designing gowns which would suitably show it off. There were now several kinds of silk based on the new invention and Philip was introducing new colours which would suit it best. He was constantly involved with dyers and discovering where, because of the local water, the best results could be achieved.

I looked forward to the days when he came and we would sit in Grand’mere’s room and talk. Cassie was often there. She would sit silently, listening, usually on a stool, her knees crossed and her hands clasped about them. She was very happy to be a part of the excitement.

My birthday was in November. Not a good time for a birthday, Julia had always said. It was too near Christmas. The best time for a birthday was in the middle of the year. She may have been right, but I was greatly looking forward to my seventeenth birthday, for it would be a sign that I had passed out of girlhood and was a young woman.

Had I been a daughter of the house there would have been a season for me; but of course there could not be one for a girl in my position.

Julia’s season did not appear, so far, to have done a great deal for her. She was still, as Grand’mere cynically said, “on the market.” She was quite discontented and, I think, a little deflated because she had had no proposal of marriage. As I said to Grand’mere, it must have had a demoralizing effect on a girl.

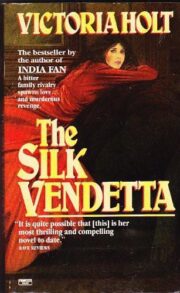

"The Silk Vendetta" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Silk Vendetta". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Silk Vendetta" друзьям в соцсетях.