”Julia,” I said firmly,’ ‘it wasn’t my fault. It was Charles …”

She just looked at me stonily and ran out of the room. I could see that she was ready to burst into tears.

I knew, of course, that she had felt deeply about Drake, and now she was blaming me because she had lost him.

The Engagement

Although I could never pass the mausoleum without recalling the terror of my incarceration there, my dreams were no longer haunted by that dank underground chamber with the rows of coffins and the lifelike statues.

Charles stayed away for a long time. He even spent the next Christmas at the home of a friend, coming home on Boxing Day just to see the family and not even staying the night. Our first meeting was a little embarrassing, but he had obviously determined to behave as though that distressing incident had never taken place, and I was glad to do the same. He was distant, cool, but not unfriendly. It was the best way to behave.

Julia had recovered from her disappointment because at Easter she was to be presented at Court and such an undertaking demanded all her attention. I imagined she hadn’t time to spare many thoughts for Drake. His name was never mentioned except by Lady Sallonger on one occasion who said: “What was the name of that rather charming young man who stayed here once? Was it Nelson or something?”

“Something like that, Lady Sallonger,” I said.

“I’d like you to read to me now, Lenore. It will send me to sleep. I had a rather bad night. I think I want more cushions … not that green one … the blue is softer.”

So Drake Aldringham seemed to have passed beyond our horizon.

It was decided that Julia should spend a week or so in London under the guidance of the Countess of Ballader. There were so many things she had to learn and she must be ready in every way for the great occasion.

Grand’mere was to go with her, so that she could study the current fashions, for although her work was excellent and she had that something which is called by the French “je ne sais quoi” and was entirely hers, there was a possibility that she might not be au fait with the very latest fashion. She might also acquire some new materials other than those which came to her from Spitalfields. Miss Logan, who knew of these matters having served in a very aristocratic family, assured Lady Sallonger that this was necessary.

I was with Lady Sallonger—as I often was now—when Grand’mere came to her. I was always struck by Grand’mere’s dignity. It was so much a part of her and it demanded immediate respect.

“Forgive me for disturbing you, Lady Sallonger,” she said, “but I must speak to you on a matter that is very important.”

“Oh dear,” sighed Lady Sallonger, who had an aversion to matters that were important and might be left to her to decide.

“It is this. I am to go to London. Yes, it is necessaire for Miss Julia to go. And we must see what is being worn and what we can do to give her the finest wardrobe of the season … yes, yes. I am happy for all this, but I could not go without my granddaughter. It is necessaire that I should have her with me.”

Lady Sallonger opened her eyes very wide. “Lenore,” she cried. “But I need Lenore here. Who will read to me? We are re-reading East Lynne. I need her to look after me.”

“I know that Lenore is of great service to you, Lady Sallonger, but I could not work well if she were not with me … and this is for one week only … perhaps a day or so more. Miss Logan is very good. And there is Miss Everton. They can all serve you.”

“It is quite impossible.”

They looked steadily at each other—two indomitable women, each accustomed to having her own way. It was a tribute to Grand’mere’s character and perhaps her unusual position in the household, that she won the day. Self-absorbed as she was, Lady Sallonger realized die importance of getting Julia launched into society. Grand’mere must go to London and it was clear that she would not go unless I went with her.

Lady Sallonger eventually pursed her lips into a pout and said: “I suppose I shall have to let her go, but it is not very convenient.”

“I know how you appreciate my granddaughter,” said Grand’mere with a touch of irony, “but I must have her with me. Otherwise I could not go.”

“I do not see why not… .”

“Ah, my lady, it is not always easy to see the ‘why not’ for what is necessary for others. i do not see why Miss Logan cannot look after you, and since Lenore is such a comfort to you, you will readily see why i cannot do without her on this very important occasion.”

Grand’mere was triumphant.

“It is time you had a little rest from her,” she said when we were alone. “She is demanding more and more of you. I can see that as the years pass … unless something happens to prevent it … you will be her slave. It is not what I wish for you.”

I was very excited at the prospect of going to London. Cassie was downcast because she would not be accompanying us. There was a suggestion that she should come but Lady Sallonger had very firmly said that she would need her to share some of my duties with Miss Logan.

“It is only for a week or so,” I told Cassie, “and I shall tell you all about it on my return.”

So Julia and I set out with Grand’mere on a rather blustery March day, travelling by rail, which was far more convenient than going by carriage. Cobb met us at the station and took us to the house in Grantham Square.

I was very excited, riding through the streets of London. Everyone seemed to be in a great hurry and there was bustle everywhere. Hansom cabs and broughams sped through the streets at such a rate that I feared they would ride over people in their haste. But no one seemed to think this extraordinary so I supposed it was the usual state of affairs.

As we came into Regent Street Grand’mere was alert. She spoke the names of the shops aloud. Peter Robinson’s… Dickens and Jones … Jay’s. I caught glimpses of splendid looking goods in the windows. Grand’mere was purring like a contented cat.

Grantham Square was in one of the many fashionable residential parts of London. The house was tall, the architecture Georgian and elegant. There were steps to a portico with two urns on either side supported by flimsily clad nymphs and in the urns was a display of tulips. Cobb deposited us at the house and took the carriage round to the mews at the back.

There was a butler, a footman and several servants—slightly more than those we had at The Silk House. Sir Francis was not at home so we were taken to our rooms by the housekeeper who asked us to let her know if there was anything we needed. She was an authoritative looking lady and rather formidable in her black bombazine which rustled when she walked. Her name was Mrs. Camden.

Grand’mere and I were to share a room. It was at the top of the house and large and airy. There were two beds and a small alcove in which was a basin and ewer.

Grand’mere said: “I think we shall be comfortable here. At least we are together.”

I smiled at her. I knew she was determined not to leave me alone in a house to which Charles might come back.

They were interesting days. Sir Francis arrived later that night. He was very courteous to Grand’mere. He said he had been delayed and hoped that we had been well looked after. The Countess of Ballader was arriving the next day and she would then get to work with Julia.

He wanted to take Grand’mere to the Spitalnelds works to show her the new looms and the modern way of weaving, which was causing some distress to the workers, who always thought that when something new came in it threatened their jobs.

“There are always troubles,” he said.

Grand’mere explained to him what a help I was to her and how I had a natural flair for matching styles with materials.

“She will be another such as yourself,” said Sir Francis, eyeing me with approval.

“I think that may well be so,” replied Grand’mere fondly.

I was so tired that night that I was asleep as soon as I got into bed and I awoke next morning to a feeling of excitement.

The Countess of Ballader arrived next day and took charge of Julia. She was to stay in the house while we were there. There was so much Julia had to learn. On those occasions when I saw her—and these were not often for she was almost always being put through her paces by the indefatigable Countess—I heard that on the great day she must have her hair dressed in such a manner as to support the three plumes, and a veil must be worn; her curtsy never seemed to please the Countess, though she could not see what was wrong with it. What was a curtsy anyway? One just bobbed down. Why should it be so difficult to learn? And her waist was not small enough; she had to be fitted for new corsets and she knew they were going to squeeze her so painfully that they made her red in the face; and that would be wrong too.

Poor Julia! Being launched into society seemed to be more a strenuous ordeal than a pleasant experience. But her excitement remained, though she did admit that she might be a failure at her first ball and she was terrified that no one would ask her to dance.

I had a happier time. Grand’mere and I explored London together. We looked in shop windows; we walked through the departments. Grand’mere noted the latest fashions … not only in the shops but on the ladies in the streets. There was a lack of chic, she said. She did not need to learn anything from them.

She bought a few materials and discussed with me how they should be made up.

Sir Francis took Grand’mere to Spitalfields. She came back preoccupied, I thought.

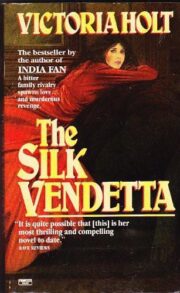

"The Silk Vendetta" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Silk Vendetta". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Silk Vendetta" друзьям в соцсетях.