"Letty is paying for my next Season?"

"Why, yes. Isn't it lovely of her to take such notice of her sisters now that she is a viscountess? A viscountess!"

"Just lovely," repeated Mary flatly. It was one thing to make the same tired rounds a fourth time, batting her eyelashes at the same rapidly diminishing crop of men, but it was quite another matter to do so on the sufferance of a younger sister. To know that every shawl, every dress, even the food on the table had been magnanimously donated by Letty for the worthy cause of helping her older sister to a husband.

On those terms, she would rather remain a spinster.

Only she wouldn't. Either way, she would be choking on her sister's charity. She could accept Letty's munificence now — and meekly submit herself to being organized as Letty saw fit — in the interest of one last, desperate bid for the comparative independence of the married state. Or she could remain unwed and be a perpetual dependent upon her parents. Which, in the end, meant being Letty's dependent, since her father's income was scarcely enough to keep him in new books and her mother in turbans. Between the two of them, they neatly dissipated the revenue from her father's small estate before one could say beeswax.

It was rather galling to face a future as a petitioner in the house where she had thought to be mistress.

"And Lord Pinchingdale will be paying Nicholas's fees at Harrow! Harrow! Can you imagine! We could never have done so much."

"Nicholas must be overjoyed," said Mary.

Nicholas would be miserable. Her little brother was the despair of the local vicar, who had been enlisted to teach him the classics. Fortunately for Nicholas, the vicar was as nearsighted as he was hard of hearing, as well as being prone to drifting off at odd moments, a habit Nicholas had done his best to encourage. Mary would be very surprised if Nicholas knew how to read, much less in Latin. Being sent to Harrow would do wonders for him — if they didn't expel him first. It was undoubtedly the right thing to do. Letty always knew the right thing to do. But it set Mary's teeth on edge.

She was the eldest. She was the one who was supposed to be magnanimously funding her brother's education and using her social consequence to bring out her younger sisters. Not the other way around.

It wasn't right.

"Have you tried the duck?" Mary cut in, just to put a stop to the catalogue of all the benefits Letty planned to confer on her family now that she was a viscountess — a viscountess! Her mother enjoyed the title so much that the word had acquired an inevitable echo every time she uttered it.

"Duck?"

Mary took her mother by the arm and steered her towards the refreshment table. "Yes, duck. I hear it's very good. There's also game pie."

Unfortunately, she didn't think food would do much to fill the hollow feeling that seemed to have settled into the pit of her stomach. It was the same feeling she had had in the gallery before Vaughn appeared, only ten times worse. In the space of three months, she had become superfluous. The grand match she had intended to make had been made by Letty; the benefits she had intended to graciously bestow upon her family were already being bestowed — by Letty. What was there left for her? Nothing but to sit and wait and be an object of charity, fed on Letty's leavings.

As if she had read her mind, Letty spotted Mary and their mother and began to bear down on them. In her hands, she held a plate piled high with food, and her face bore its most determined housewife expression. Someone was going to be fed, and they were going to be fed now.

It wasn't going to be Mary. Without a qualm, Mary tossed her mother to the wolves. "Look!" she called out cheerfully, giving her mother a little shove in the direction of her sister. "Isn't Letty lovely? She's prepared a plate for you."

"Darling!" Mrs. Alsworthy exclaimed, and made for Letty with both arms outstretched, although whether to embrace her or to snatch up the plate was largely unclear.

Mary didn't wait to find out.

Leaving her relations to it, Mary hastily made her exit stage left, back into the relative quiet of the upper gallery. It should take Letty some time to extricate herself from the maternal embrace. Well, it was only fair, Mary decided. If Letty wanted to be a two-darling daughter, there was a price to be paid.

Mary had her mind set on a very different sort of price. Lifting her skirts clear of the dusty floor, she made straight across the upper hall into the Long Gallery. The painted Pinchingdales held no fascination for her this time. She strode rapidly past them, seeking the living rather than the dead. There was no one standing between the torches, no one sitting on the window seat. The gallery was empty, deserted.

Mary reached the window and turned, thwarted. Where was he? She would have seen him had he returned to the Great Chamber. There had been no sign of movement downstairs in the hall. Of course, he might have retired to his room or gone out to the gardens or climbed up to the battlements to howl at the moon. He could be anywhere in the vast old pile. He might even have left — really, truly left.

That was too dreadful a prospect to be thought of. She had to find him. Because anything, anything at all was better than spending the winter hearing her mother sing an endless chorus of the wonders of her sister, while she herself faded into something not quite alive. She would see just what sort of price Lord Vaughn's theoretical flowery friend was willing to pay. And if Vaughn himself was the Black Tulip…well, then, surely the government must provide rewards for that sort of discovery.

But where had he got to? She couldn't very well seek him out in his bedchamber. That would spell ruin, and Vaughn, Mary could tell, was not the marrying kind.

Not like Geoffrey.

Of course, even being truly ruined would be more interesting than another evening of game pie.

Hands on her hips, Mary stalked over to the red velvet curtain by which Vaughn had posed when he first appeared earlier that evening — and stopped, her eye caught by a glimmer of light where there had been none before. The archway half-concealed by the curtain led off into the western half of the wing that fronted the garden, the bottom half of the second long stroke of the H. Earlier that evening, both corridors leading off the gallery had been dark and still. Now, lamplight seeped across the floor, coming from a partially open door just a little way down the corridor.

A superstitious shiver snaked down Mary's spine. Framed in red velvet, the deserted hallway might have been a stage set for Don Giovanni, black as a scoundrel's heart except for the reddish tint of hellfire to come. She could, of course, go back to the safety of the Great Chamber. She could fix her mother's plate and listen to her tales of success at the Littleton Assemblies.

Brimstone, it was.

Squaring her shoulders, Mary set off to strike her bargain with the Devil.

Chapter Four

Better to reign in hell, than serve in heav'n.

A skull made a very restful companion.

Stretching one leg out in front of him, Vaughn settled more comfortably into the squashy interior of a squat wooden chair. In front of him, paired peasants shouldered the burden of the hooded mantel, grinning at an unpleasant rural secret. The little room must once have served an undistinguished purpose, antechamber to a grander room or perhaps even a privy, but at some point in the last century the room had been converted into a private den, lined with books and tricked out with the latest in the Gothic style. A blackened walnut table had been fitted out with an illuminated medieval manuscript, placed next to a decanter and goblets hammered out of semi-precious metal and set about with misshapen chunks of colored glass meant to look like a prosperous chieftain's hoard. The skull, grinning winningly from one corner of the table, completed the scene. A tentative tap of the fingernail confirmed that it was not, in fact, a plaster facsimile.

No detail had been neglected. Gargoyles stuck out their tongues from the joins in the vaulted ceiling, and a mirror had been cunningly angled above the fire to mirror and magnify the stained-glass window hung above the door. The distorted reflection transformed the tiny chamber into a towering cathedral, licked at the edges by the orange flames of the hearth. A cunning illusion, reflected Vaughn, as long as one didn't look away from the mirror.

But then, that was the way of illusions, wasn't it? All charlatans, whether the stage magician or the amorous rake, relied upon man's yearning to be deceived, to gaze in the mirror of his own desirings and be gulled by the image therein. It was a tempting prospect, to look and believe, like Faust panting after Helen's shadow. In the end, however, the mirror always cracked, revealing the images for the shams they were. Loyalty, love, the joys of home and hearth — no more substantial than an opium dream and just as debilitating while they lasted.

Of course, none of the earnest young people cavorting in their innocent frolics in the Great Chamber would admit a word of it. They all believed in fates worse than death, True Love in capital letters, and the innate goodness of man. Even Jane, for all her perspicacity, suffered from an unaccountable attachment to abstract notions of honor. Except, perhaps, for Miss Alsworthy.

Now there was something out of the ordinary.

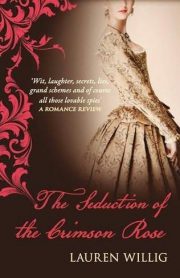

"The Seduction of the Crimson Rose" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Seduction of the Crimson Rose". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Seduction of the Crimson Rose" друзьям в соцсетях.