The girl in the lake was methodically and dedicatedly washing herself. And as soon as he realized this, he knew who she was.

Chivalry now dictated, unquestionably, that Rupert should turn and move silently away. Instead, he stepped back into the shelter of a copper beech and waited.

Anna had finished washing now and, putting down the soap, she twisted her hair into a knot high on her head and began to walk slowly into the water.

She might get into trouble, Rupert reasoned with himself, for there was a place where the tree roots went deep into the lake. I’d better stay.

But there was no question of her getting into trouble; he knew that perfectly well. She swam easily and somehow, across the silent water, he caught her delight, her oneness with the dark water and the night.

It was when she finally turned for the shore that Nemesis overtook her in the form of Baskerville, finished with his rabbit, bounding over to the water and barking for all he was worth.

‘Durak! Spakkoina! Sa diss!’ She began to berate the dog in her own language, her voice low and husky and a little bit afraid, while she endeavoured to wrap herself into her towel. Baskerville, suddenly recognizing her, made matters worse by leaping up and trying to lick her face.

Rupert’s voice, curt and commanding, dissolved this tableau in an instant.

‘Here!’ he ordered. ‘At once. And sit!’

Baskerville came, grovelled, and keeled over, doing his felled-ox-about-to-be-conveyed-to-the-slaughterhouse routine, his legs in the air. Rupert left him, picked up the bundle of clothes she’d abandoned on a flat stone and walked over to the girl.

‘You win,’ he said. ‘I’ll build some bathrooms.’

She took them, still clutching her towel. ‘Are you angry?’ she asked. ‘You should not be, because nowhere does it say in the book of Selina Strickland that one may not wash after working hours in the lake of one’s employer.’ And, as Rupert remained silent, she went on anxiously, ‘You will not dismiss me?’

‘No, I will not dismiss you. But get dressed quickly. It’s getting cold. I’ll turn round.’

It took her only a moment to slip into her brown housemaid’s dress. Still barefoot, her wet hair tumbling round her shoulders, she looked, as she came towards him, like a woodcutter’s daughter in a fairy tale. Rupert put out a hand and felt hers, work-roughened and icy. Then he took off his coat and draped it over her shoulders.

‘No!’ Anna was shocked. ‘You must not do that. It is very kind but it is not correct,’ she said, adding with devastating effect, ‘my lord.’

A faint terror lest she should begin to curtsy took hold of Rupert.

‘Do you often come out at night like this?’ he asked.

Anna nodded. ‘Housework is not uninteresting exactly, but it is very dirty. And I do not understand… I mean, in Russia my gover… in Russia we were always being bathed. Hot baths, cold baths and the English grocer in the Nevsky had seven kinds of soap. But here…’

So she had had a governess, his new housemaid. He was not surprised. Suddenly he felt, rather than saw, a new and fiercer anxiety take hold of her.

‘You have been here a long time?’ she hazarded. ‘You saw me… swimming?’

Rupert was silent, waiting for tears of indignation or the fury of modesty defiled.

Anna covered her face with her narrow, El Greco hands. Now her head came up and she peered at him through tragically splayed fingers.

‘I am too thin?’ she enquired.

And surprising himself by the fervour with which he lied, Rupert said, ‘NO!’

News of Rupert’s engagement, spreading to the servants’ hall, the outdoor staff and so into the village, was received with universal delight. Miss Tonks and Miss Mortimer, the pixilated spinster ladies who lived in Bell Cottage and had, as long as anyone could remember, done the flowers in the church, began putting their heads together, pondering on the floral decorations that should be worthy of such an occasion. Mrs Bunford, the village dressmaker, bought three new pattern books so as to be completely up to date in the event of a summons from the house, and the vicar, scholarly Mr Morland who had christened Rupert, was touched and happy at the idea of marrying him.

As for the Mersham servants, it was only when the weight of anxiety was lifted that they realized how great it had been. Proom had secretly had no doubt that they were refurbishing Mersham only to put it up for sale and, while he himself only had to hint that his services were on the market for offers to come flooding in, his mother was hardly an exportable commodity. Mrs Park’s anxiety had been for Win, her simpleminded kitchen maid. Louise, though she seldom spoke of it, was the sole support of an invalid brother in the village. So, as they drank to the health of Miss Muriel Hardwicke in the earl’s champagne, emotion and goodwill ran extremely high.

‘And if the wedding is to be at the end of July I shall still be here,’ said Anna, whose engagement had now been extended to the end of that month, ‘which I shall like very much because I have never been to an English wedding and Russian weddings are very different, with people standing under high crowns for two hours and everybody falling down and fainting.’

As for the dowager, she left her planchettes and her ouija board, drew back the curtains of her twilit boudoir and began to make lists. She made lists for Mrs Bassenthwaite about the catering and lists for Proom about the disposition of the house guests. She made lists of the relations she was going to invite to the wedding and the acquaintances she was going to inform of it, and as soon as she made the lists, she lost them. Yet out of the fluffy cloudiness of her mind and the chaos of her boudoir there emerged the design, masterly and graceful as Mersham itself, of a country wedding in high summer. A wedding in which everyone in the house and the village would most joyfully share.

The first person to call and congratulate Rupert was his friend and best man, Tom Byrne, driving over from Heslop Hall.

Heslop was less than ten miles from Mersham, a great Elizabethan pile, sumptuous and tatty, which had harboured broods of roistering Byrnes for centuries. The Byrne children had played with George and Rupert, had ridden in the same gymkhanas, been to the same parties. It was natural that Tom, who had miraculously survived four years in the infantry without a scratch, should be Rupert’s best man, and he came now also to offer his family’s help in welcoming Muriel. But both Rupert, coming forward to greet him, and the servants, peeping out of the ground floor windows, forgot the wedding and everything else for they saw that Tom had brought no less a person than the Honourable Olive.

Ollie Byrne was just on eight years old and anyone speaking ill of her within fifty miles of Heslop or of Mersham would have found themselves lying flat in a gutter with a bloodied nose. The Byrnes had already had three lusty, red-headed sons: Tom, the eldest, Geoffrey and Hugh, when Lady Byrne, though in failing health, found herself pregnant once again. She only lived long enough to give birth to a premature and hopelessly delicate daughter before she died. The baby, hastily christened Olive Jane, spent the first year of her life in the prison-like wards of a famous teaching hospital, more as an aid to medical research than because the pathetic, screwed-up bundle seemed to have any chance of life. As for Ollie’s father, Viscount Byrne, presented with three sons to bring up and an infant daughter in distant London, he sought for a new wife with a frenzy he made no effort to conceal.

His choice fell, somewhat arbitrarily it was felt, on an American, Minna Cresswell, the daughter of a New York shipowner whom he happened to be standing next to at Goodwood. Confronted by a new stepmother, within a year of their mother’s death, Tom, Geoffrey and Hugh glared, scowled and swore eternal enmity. Minna was small, quiet and mousy-looking and seemed to have nothing but her fortune to commend her to anyone’s attention.

The new Lady Byrne made no attempt to ingratiate herself with the boys. She didn’t ask them to call her ‘Mother’, they were in no way bidden to love her, nor did she hand out expensive gifts. Her practical actions were confined to quietly modernizing those parts of Heslop which were in danger of collapse; and even this she did so discreetly that new bathrooms and radiators appeared as if by magic, without upsetting either her lord’s hunting or his meals. And every week she motored to London to breathe her will into the tiny, jaundiced bundle that was the Honourable Olive.

Within a year, the boys were rushing into the house calling ‘Mother!’ before they had even taken off their coats. When she was away, Byrne prowled his mansion like a labrador deprived of game — and Ollie, spewed up from her teaching hospital at last, decided to live. Not only to live but to conquer. At three, a pair of huge round spectacles perched on her freckled nose, she departed gallantly for weekend visits in the English manner (clutching, however, a rolled-up rubber sheet in case of accidents). At four, though still tiny, she learned to ride.

So when, at the age of five, she contracted tuberculosis of the hip, the blow was shattering. Once again, Ollie went away from home to be immured for two interminable years in a Scottish sanatorium, where she lay, her little pinched face peering above the blankets, on freezing verandas, immobilized in a series of diabolical contrivances. It was in that sanatorium that the nurses, seeing how the child bravely coped with the recurring, debilitating fever and the agony of secondary osteomyelitis, turned the meaningless prefix, ‘the Honourable’, into a badge of office — and the Honourable Olive she was destined to remain.

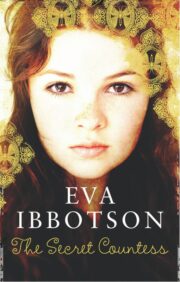

"The Secret Countess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Countess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Countess" друзьям в соцсетях.