‘Come in, my dear. You’re the Russian girl, aren’t you? Now I want you to take a very important message. It’s for Mr Firkin, the sexton. Can you find his house, do you think? It’s just opposite the church with the walnut tree in the garden.’

‘Yes, my lady, I’m sure I can.’

‘Good. Now I want you to tell him that a message has just come through from his wife. At least I think it must be his wife. She said her name was Hilda and I’m sure Mr Firkin’s wife was called Hilda. Yes, I know she was because…’ She broke off and began to rummage in her escritoire. ‘Now where was I?’

‘You were going to give me a letter, my lady.’

‘That’s right; here it is. The poor woman really sounded desperately worried. For some reason she cannot bear the idea of him giving away his top hat. It’s strange how these things seem to go on mattering, even on the Other Side.’

Anna took the letter and bent to pick up the scarf that had slipped from the dowager’s shoulders. She was rewarded by a charming smile, which changed, suddenly, to a look of intense scrutiny.

‘My goodness! Really that is most remarkable. Just stand over there, dear, where I can see you properly.’

Puzzled, Anna went to stand by the window.

‘Most unusual, really, quite amazing. You can be very, very, proud.’

‘Proud of what, my lady?’

‘Your aura. It’s one of the purest and most beautiful I’ve seen. Especially the orange. Only it isn’t orange so much as flame. But a very gentle flame. Like candlelight. Like starlight, even.’ She broke off. ‘Oh dear! What is the matter? What have I said?’

‘It’s nothing,’ said Anna, wiping away the sudden tears. ‘I’m so sorry. It’s something my father used to call me. I will go and find Mr Firkin straight away.’

Forgetting, for once in her life, to curtsy, Anna fled.

And so, day by day, Mersham yielded to the energy and attack of its staff and grew more beautiful. The shutters were thrown open to the light, Ted brought tubs of poinsettias and lilies into the house. The silver table pieces, burnished by James to unbelievable perfection, were returned to the state dining room, the freshly washed chandeliers sparkled in the sunlight. The men took their liveries out of mothballs; new aprons were assigned to the maids.

Till, on a hot night in mid-June, Anna, who had that day polished the one hundred and thirty-seven banister rails of the great staircase, crawled along the interminable parquet floor of the long gallery with her tin of beeswax and turpentine and beaten fifteen Persian rugs, opened her attic window, leant her weary head on her arms and said to the absent earl:

‘It is ready now. You can come.’

And the next day, he came.

2

He came down by car, driving himself in the old black Daimler that had been his father’s and as the familiar landmarks appeared, his apprehension increased.

Rupert had neither wanted nor expected to inherit Mersham or the burdens of the title. It was George who had had all the makings of a landowner and a country gentleman: outgoing, debonair George, whose bones now lay deep in the soil of Flanders. Rupert had seen his beautiful home as a place of refuge to which he might occasionally return, but his ambitions had lain elsewhere: in scholarship, in music — above all in travel. The high, wild and undiscovered places of the world had been the stuff of Rupert’s dreams all through his childhood. That being so, it had been no hardship to grow up in his brother’s shadow. Shadows are cool and peaceful places for those whose minds are overstocked with treasure.

Rupert’s three years at Cambridge had seemed a glorious preparation for just such a life. He took a First in history and was invited by his tutor, a brilliant madman who specialized in North Asian Immortality Rites, to join him in a field trip to the Karakorum.

Instead, the autumn of 1914 saw Rupert in the Royal Flying Corps, one of a handful of young pilots who took off in dilapidated BE2s from airfields conjured up in a few hours out of fields of stubble, bivouacked between flights in haystacks and ditches. Two years later, when George was killed at Ypres, Rupert was in command of a squadron flying Camels and Berguets against Immelmann and the aces of the German Reich. The chance that he would survive to inherit Mersham seemed so remote that he scarcely thought of it.

Then, in the summer of 1918, returning alone from a reconnaissance, he was set upon by a flight of Fokkers, and though he managed to dispatch two of them, his own plane was hit. The resulting crash landed him in hospital, first in St Omer, then in London. Some time in the months of pain that followed they gave him the DFC for bringing his plane back across the lines in spite of his wounds, but his observer, a moon-faced kid called Johnny, died of his burns, and the manner of his dying was to stay with Rupert for the rest of his life.

And while he lay in hospital, tended by a series of devastating VADs, the war ended and Rupert found himself still alive.

Alive, and Seventh Earl of Westerholme, owner of Mersham with its forests and farms, its orchards and stables. Owner, too, of the crippling debts, the appalling running costs, the mortgage on the Home Farm.

It was only the memory of George on the last leave they’d spent together, that prevented Rupert from instructing his bailiff to sell then and there. George, his eyes glazed, his uniform unbuttoned after an evening of conventional debauchery at Maxim’s, turning suddenly serious. ‘If anything happens to me, Rupert, try and hang on to Mersham. Do your damndest.’ And as Rupert remained silent, he had added a word he seldom used to his younger brother. ‘Please.’

So Rupert had promised. Yet as he pored over the documents they brought to him in hospital he saw no way of bringing the estate, so hopelessly encumbered, back to solvency. And then, suddenly, this miracle… this undreamt of, unhoped-for chance to make Mersham once again what it had been and see that all the people in his care were safe.

Thinking with an upsurge of gratitude of the person who had made this possible, his apprehension lifted and, stepping on the accelerator, he turned in past the empty gatehouse, drew up on the wide sweep of gravel and braced himself against the onslaught of the lion-coloured shape now tearing down the steps towards the car.

He was home.

‘Welcome home, my lord,’ said Proom, coming forward to greet him. ‘I trust you had a comfortable journey?’

‘Very comfortable, thank you, Proom,’ said Rupert. He broke off: ‘Good heavens!’

Proom followed his master’s gaze. On either side of the grand staircase with its Chinese carpet and crystal chandeliers, stretching upwards like ranking cherubim, were Rupert’s footmen in livery, his housemaids in brown, his kitchen maids in blue, his scullery maids and hall boy and housekeeper and cook. Compared to pre-war days they were a mere handful, but to Rupert, accustomed now to the simplicities of wartime living, they seemed to reach to infinity.

‘As you see, I’ve assembled the indoor staff, my lord,’ said Proom somewhat unnecessarily. ‘It was their wish to greet you personally after your ordeal.’

If Rupert’s heart sank, there was nothing to be seen in his face except pleasure and interest. He went forward, his hand outstretched.

‘Mrs Bassenthwaite! How well you look!’

‘And you too, my lord,’ lied the old housekeeper. They had read about him in the papers for, surprisingly, it was Rupert not George who had been twice mentioned in dispatches, had won the MC while still a subaltern and become — even before his final act of bravery — a legend to his own men. Now the old woman who had known him since his birth saw in the new lines round his eyes, the skin stretched tight across the cheekbones, the price paid by those who force themselves against their deepest nature to excel in war.

‘And Mrs Park! Well, if you’re still presiding over the kitchens it will be worth coming home.’

He walked on slowly, greeting all the old servants by name, cracking a joke with Louise, asking, with a grin, after James’s pectoral muscles, enquiring if the second footman felt his wound.

He had reached the half-landing and Proom, very much the major domo, was at his side, introducing a new maid.

‘This is Anna, my lord. She is from Russia and has joined us temporarily.’

Rupert only had time to register a pair of intense, dark eyes in a narrow, thoughtful face before the new girl curtsied.

All the girls had bobbed curtsies as he passed, but Rupert was about to encounter for the first time this weapon of social intercourse in Anna Grazinsky’s hands. One arm flew gracefully outward and up like an ascending dove, her right foot, elegantly flexed, drew a wide arc on the rich carpet — and she sank slowly, deeply and utterly to the ground.

Panic gripped Rupert. Even Proom, immune as he was to the devastating effect of Anna’s curtsies, stepped back a pace. For here was homage made flesh; here, between the bust of an obese Roman emperor and a small, potted palm, Rupert, Seventh Earl of Westerholme, was being offered commitment, servitude, another human being’s all.

Rupert instinctively looked round for the red roses that should have been raining down from the gallery, the bouquet which anyone not made of iron must surely bring in from the wings. For unlike Proom, who had merely suffered uncomprehendingly, Rupert recognized the origin of his new housemaid’s curtsy. Thus had Karsavina sunk to the ground after her immortal rendering of Giselle; thus had Pavlova folded her wings after her Dying Swan.

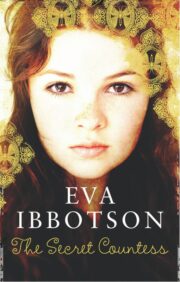

"The Secret Countess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Countess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Countess" друзьям в соцсетях.