In the east wing, James, offering to valet Uncle Sebastien, had been repulsed by the sour-faced nurse, who was now helping the old man to get ready, talking to him like a child, with a dreadful, arch coyness. ‘We’re going to be very important today, aren’t we? We’re going to give the bride away, aren’t we? So we don’t want any nasty cigarette ash on our nice clean clothes, do we?’

And in her bedroom the baulked and furious Lady Lavinia snapped the gold bracelet that had been the bridegroom’s present to the bridesmaids on to her scraggy wrist and went along to Queen Caroline’s bedchamber.

But at the sight of the bride even Lavinia’s ill-temper subsided and she gave an involuntary gasp of admiration. Flanked by the obsequious Cynthia and the new Swiss maid who had providentially arrived the day before, standing erect and without a trace of nervousness in her glorious ivory dress, the future Countess of Westerholme was quite simply breathtaking.

‘My prayerbook and my gloves, please,’ she ordered. ‘Cynthia, pick up my train. I’m ready.’

Mr Morland, robed and waiting in the vestry, came forward with outstretched hands to greet the bridegroom. If the medieval saints had gone to their deaths as to a wedding, the Earl of Westerholme, thought the kind and scholarly vicar, looked as if he was preparing to invert the trend.

‘I’m afraid Mr Byrne’s not here yet,’ he said, concealing his surprise, for the best man had hitherto been most punctilious in the performance of his duties.

He moved over to the door and stood looking out at the congregation. Sad that the bride had no relatives at all. In the packed church only her erstwhile chaperone represented her side of the family. At the organ, Miss Frensham was peering with her half-blind eyes at the keys, anxiously memorizing the strange piece that Miss Hardwicke had ordered instead of ‘Lohengrin’. The formal urns of lilies, the gardenias and carnations stiffly wired to the pew ends by the London florists who had replaced Miss Tonks and Miss Mortimer gave off an almost overpowering scent.

Mr Morland frowned. What was it that struck him as so unusual?

And then he realized. Absolutely no one was crying! Strange, thought Mr Morland, who could not remember such a thing. Exceedingly strange.

But if no one was crying there was one member of the congregation who was clearly in extremis. Dr Lightbody, sitting beside old Lady Templeton in the pew behind the dowager, was in a piteous state. Sweat had broken out on his forehead, his hands were shaking and once he rose in his seat and threw out an arm as if he were about to break into anguished speech.

‘Are you ill?’ whispered Lady Templeton, who could not approve such conduct in the House of God. ‘Do you wish to go out?’

The doctor managed to shake his head, but the phantoms that had haunted him since the Mersham butler, nursing a grievance against the family as these old retainers were apt to do, had been to see him, ran riot in his brain. For the fate awaiting Muriel Hardwicke was too terrible to contemplate. This white goddess, this vessel of perfection was going — and on this very night — to be most hideously defiled by the satanic brute that she had chosen to espouse. And he had been too weak to save her. Well, it was too late now. He closed his eyes, buried his head in his hands. Let him at least not see…

Five minutes passed, ten… The congregation was growing a little restive. Miss Frensham’s store of introductory music was running dangerously low. But it was not the bride who was causing the delay. It was the best man, who should have been here hours ago to help and succour the bridegroom.

‘Of course his presence is not essential to the ceremony,’ said Mr Morland. ‘Even if he has the ring.’

But now Tom came striding into the vestry. His apologies were perfunctory, his expression grim and it was almost with hostility that he led Rupert — whose sense of being caught in a nightmare from which he could not wake was growing stronger by the minute — to the chancel steps.

And now it was beginning. With her old mouth nervously puckered, Miss Frensham began to play the strange piece demanded by Miss Hardwicke — and on the arm of Mr Sebastien Frayne, the bride entered.

A gasp of sheer admiration greeted her. A slightly different gasp followed the entry of the two adult bridesmaids in their pink ruffles and petalled caps.

Then a rustling, whispers of surprise, of indignation, murmurs of disappointment, puzzled looks…

The bride reached the altar rails, handed her prayerbook to the Lady Lavinia; Mr Morland cleared his throat, when the voice of the bridegroom was heard saying clearly and imperiously, ‘Wait! Where is the third bridesmaid? Where is Ollie Byrne?’

Tom turned to his friend. Everything in him longed to blurt out what Muriel had done. Longed to show him Ollie as he had left her, lying white and despairing in her bed because there was nothing, now, to get up for and nowhere, now, to go. Ollie, who had seen so totally and searingly through Muriel’s concern for her health, her unctuous bribery… who had told the nursemaid coming to brush her marigold curls that there was no point because cripples didn’t need to be tidy, and now lay with her face to the wall beyond reach of comfort or of hope.

But Muriel, shocked at a voice raised in church, whispered, ‘Hush, dear. Ollie isn’t well, it seems,’ — and Mr Morland bent his head and began to repeat what are surely the best-loved words in the world:

Dearly beloved, we are gathered here in the sight of God and in the face of this congregation, to join together this Man and this Woman in Holy Matrimony…

But Tom’s disclosure would have been superfluous. Rupert had understood, and as clearly as if he were again present he remembered Ollie’s sad little question in the taxi on the way from Fortman’s and his own answer: ‘If you are not a bridesmaid at my wedding then there will be no wedding, and that I swear.’

Only there was a wedding. He was in the midst of it. He was marrying Muriel Hardwicke.

… but reverently, discreetly, advisedly, soberly and in the fear of God, duly considering the causes for which Matrimony was ordained.

First it was ordained for the procreation of children…

In his pew, Dr Lightbody groaned. The procreation of children yes… But what children? What monsters, what fiends in human form would that lewd and treacherous earl beget on the unsullied body of his bride? Oh, God, was there no one to warn her, no one to whom she could turn?

… for the mutual society, help and comfort that the one ought to have of the other, both in prosperity and adversity. Into which holy estate these two persons present come now to be joined. Therefore if any man can show any just cause why they may not lawfully be joined together…

I gave my word to Ollie, thought Rupert — and lifted his head. But it was not his own voice which suddenly tore through the church: the frenzied voice of a human soul in torment, crying: ‘Stop! Oh, stop! This marriage must not be!’

Mr Morland looked up. The startled silence which followed was broken only by the small exclamation which escaped Lady Templeton as the doctor, stumbling from his pew, stepped heavily on her bunion.

‘It must not be!’ repeated Dr Lightbody, his pale eyes glittering now with a Messianic fervour. He brushed aside the Lady Lavinia, reached the altar rails: ‘This lovely woman has been most hideously deceived!’

The vicar blinked. In her pew, the dowager, who had read Jane Eyre no less than seven times, shook her head in disbelief. And Muriel, within minutes of her goal, turned furiously on the doctor.

‘You seem to have taken leave of your senses, Dr Lightbody.’ And to the vicar, ‘Pray, proceed.’

‘No, no!’ The doctor was now quite beside himself. ‘You must listen, Miss Hardwicke. You are in danger — terrible danger! There is tainted blood in the Westerholmes!’

‘Nonsense!’ But Muriel’s pansy-blue eyes had dilated in sudden fear. ‘It isn’t true, Rupert?’

‘Of course it isn’t true,’ said Rupert contemptuously.

‘It is true, it is true!’ screamed Lightbody. He pointed with a shaking finger at the earl. ‘Ask him what is hidden in the folly in the woods. Ask him, Miss Hardwicke. Ask him!’

The whispers and murmurs among the congregation were growing to a climax.

‘Ask him,’ yelled Dr Lightbody. ‘And if you don’t believe me, ask him!’ And he swivelled round to point at Mersham’s butler, sitting composed and immaculate in the back pew. ‘Go on! Ask Proom!’

The name, with its overtones of high respectability, rang through the church. Mr Morland, who had been about to order the doctor from the church, laid down his prayerbook. And Mr Cyril Proom rose slowly and majestically to his feet.

‘Please come forward, Mr Proom,’ said the vicar. ‘I’m sure there is a perfectly respectable explanation for this gentleman’s remarks.’

Steadily, with his usual measured tread, Mr Proom advanced up the aisle. As he drew level with her pew, the dowager threw him a glance of total puzzlement and he held her eye for a long moment before he moved up to the altar rails and, bending his head respectfully, addressed the vicar.

‘I’m afraid Dr Lightbody is perfectly correct, sir. I felt it advisable to make certain disclosures to him in view of his well-known interest in eugenics. And in any case,’ he said, ‘I am owed several months’ wages by the family.’

The lie, in its pointless blatancy, momentarily pierced Rupert’s sense of nightmare and he narrowed his eyes.

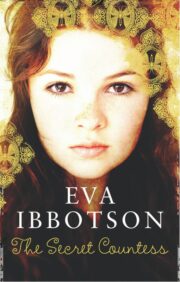

"The Secret Countess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Countess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Countess" друзьям в соцсетях.