‘What is in the folly?’ demanded Muriel, who was no longer calm. ‘Tell me at once!’

‘Imbeciles!’ cried Dr Lightbody. ‘I’ve seen them! Dreadful, dribbling imbeciles. And they’re his cousins! His first cousins. By blood.’

‘It isn’t true! Rupert, tell me it isn’t true!’

‘He won’t tell you — he won’t admit it, he wants your money. But I tell you, I’ve seen them! I saw them last night. He keeps them locked up in that tower and they’re like animals — worse than animals.’

Mr Morland’s bewilderment was total. He’d been Vicar of Mersham for twenty years and never heard a whisper of scandal. But could Proom be lying?

‘Is it really so?’ he asked the butler, above the growing uproar in the church.

‘I’m afraid so, sir. The family’s given it about that the folly’s haunted by the ghost of Sir Montague Frayne, so nobody goes near it. But the screams — well, they’re not the screams of ghosts, sir; they’re the screams of his lordship’s relatives.’

Rupert had been listening to this farrago of nonsense in silence. Now he turned and raised enquiring eyes at his mother.

The dowager rose and slipped from her pew. There was the sound of tearing silk as she threw up her arms to embrace her son. Then:

‘Oh, Rupert, darling,’ she exclaimed in tones of theatrical despair, ‘don’t you see? The game’s up!’

Proom had been against Myrtle Herring pretending to be a chicken laying an egg. It was his opinion that people asked to simulate mental derangement always picked on chickens and the routine, wing flapping, squawking performance was invariably hackneyed and unsatisfactory.

Myrtle, however, had convinced him. Myrtle had been in vaudeville and during their run-through in the folly, sitting atop a pile of straw, brought to her frenzied cluckings such an extreme of gynaecological anguish rising — as she examined the imagined egg — to such awed and ecstatic triumph, that Proom had been deeply impressed.

He had expected to encounter some difficulty in persuading the Herrings, as he conveyed them by a roundabout route to the back gates of Mersham, to follow his plan. True, they were lucky not to be in prison. Still, they had expected to come to a wedding. Instead, he proposed that they should give a full performance in the folly tower for the benefit of Dr Lightbody, spend the night there (albeit surrounded by oil stoves, mattresses and a hamper of food sent up by Mrs Park) and then — all traces of these comforts having been removed — give a repeat performance should the doctor decide to speak.

No persuasion had been needed. The sight of one hundred pounds in notes with the promise of another three hundred to come, should they succeed in convincing Miss Hardwicke that they really were deranged, had stilled all doubts. Not only that, but in setting the deception up they had proved to be cooperative and creative. The scruples that had troubled Proom and Mrs Park, the accusation they had levelled at themselves of appearing to make light of the mentally afflicted, did not trouble the Herrings. Nothing troubled the Herrings faced with four hundred pounds.

Towards the folly, then, in its setting of deep woodland, came the wedding party. Proom was at its head, his expression grave, his bearing deferential. Dr Lightbody followed, the bearer of terrible news, the man who had taken fate into his own hands and felt the decision pressing on him almost unbearably. Then came Muriel, holding up the train of her dress, still stately but no longer composed, and beside her, Rupert, convinced that his grasp on reality had finally slipped away. The dowager, the old Templetons, and Mr Morland, escorted by Tom Byrne, brought up the rear. Everyone else had been persuaded to stay behind.

The padlock on the door yielded to Proom’s fingers, the door creaked back. A smell of damp and decay met them, cobwebs brushed their faces…

‘But this is disgusting,’ said Muriel. ‘What—’

She was arrested by a scream. A truly horrible scream, followed by a burst of cackling laughter.

‘This way, miss,’ said Proom — and led the way up the round, dank stairs to the first of the tower rooms.

The thing that lay on the floor must once have been human, but it did not seem human now. Its face was livid and distorted, it had burrowed into the straw like an animal, its filthy fingers tore and clawed at its ragged clothes.

‘Good heavens!’ Old Lady Templeton was deeply shocked. ‘It can’t be… surely that’s poor dear Melvyn, isn’t it?’

‘Quite so, my lady.’ Proom turned to Miss Hardwicke. ‘This… er, gentleman, is his lordship’s first cousin, Mr Melvyn Herring.’

‘Oh my God!’ Muriel’s poise was shattered at last. She was as pale as her wedding dress. ‘No, I don’t believe it. His first cousin!’

‘Yes, miss. You will see he has the Templeton eyes and — oh, careful, miss.’

For the thing had arched its back, blobs of spittle came from its mouth — and suddenly it sprang.

It was Dr Lightbody who saved Muriel, dragging her back before the demented creature could sink its teeth into her hand.

‘He’s been like this for a while, miss, and I’m afraid he’s getting worse.’

‘But there are others,’ cried Dr Lightbody. ‘Dearest Miss Hardwicke, there are others! This monster has been allowed to marry, to beget other tainted beings.’

Proom inclined his head. ‘Dr Lightbody is correct. If you would care to follow me.’

They ascended another dark and curving staircase to the next room. On the floor lay two enormous boys, to all outward appearance, boys of fourteen or fifteen. But they wore nappies, their fingers were in their mouths; one drooled, the other hiccupped…

‘Master Dennis and Master Donald Herring,’ announced Proom. ‘As you see, they have remained in an infantile stage. The doctor gives no hope of improvement.’

‘It isn’t possible!’

But even as she spoke, Muriel saw that it was possible. Like the mad thing that was their father, these boys had the grey, gold-flecked eyes, the short nose of the Templetons.

A last flight of steps and they reached the top of the tower.

Myrtle had made a splendid nest. There were feathers in her hair, a deep and committed broodiness lit up her features and, even as they watched, she emitted a loud and fulfilling squawk…

‘And this is Mrs Herring,’ said Proom. ‘She, of course,’ he added conscientiously, ‘is no blood relation.’

But Myrtle Herring had been too much for Rupert. And collapsing against a wall, he began to laugh.

It was this laugh which finished Muriel. Hysteria, another dangerous mental aberration, began in just this unbridled way — and stepping forward she slapped him hard across the cheek.

‘You swine! You unmitigated, vile, scheming swine! Trying to get my money out of me! Trying to trap me into a marriage so that I could bear you some more deformed and squirming… things. I’ll have you for this, Rupert! You’ll pay me back every penny I put into that estate — every brass farthing, and the damages I’ll sue you for!’

‘Oh, Miss Hardwicke, if you would only take my protection!’ cried the doctor. ‘We could go to America! I could make you the priestess of the New Eugenics. You would be a goddess to me all my life!’

‘And your wife?’ said Muriel coldly.

‘She is dead.’

Muriel registered this information with a flicker of her pansy eyes. Then she began to remove her engagement ring. The doctor’s pale, beautifully manicured hand, closing over the solitaire diamond like a vice, prevented her.

‘I’m sure his lordship would want you to keep it as a memento.’

Rupert, still weak from laughter, nodded.

‘Yes, indeed! Do please keep it, Muriel.’

‘Very well.’ She replaced the ring, gathered up her train. ‘Come, Dr Lightbody.’

‘Ronald,’ he begged.

‘Come, Ronald,’ said Muriel Hardwicke, and with a last look of disgust and loathing, swept down the stairs.

16

‘I can’t write a letter like that, Mr Proom,’ said Mrs Bassenthwaite weakly. ‘Not to a countess, I can’t.’

Ten days had passed since the interrupted wedding and Mrs Bassenthwaite, released from hospital, was convalescing on the sofa in the housekeeper’s room.

‘I’d write it myself,’ said Proom, ‘but it would be better coming from you. More correct, you being in charge of the maids.’

Mr Proom had emerged as a local hero, sharing with Leo Rabinovitch and the Herrings, the acclaim of the entire district during the merrymaking which had followed the departure of Miss Hardwicke. Even the knowledge that Mersham would almost certainly have to be sold in order to meet the demands of Miss Hardwicke’s solicitors had not diminished the delight of the villagers, the tenants and the gentry in being rid of a woman so universally detested. To the general happiness, however, there was one exception — the earl himself, who had put Mersham’s affairs into the hands of his agent and was about to depart for the Hindu Kush.

‘I’ll tell you what to say,’ persisted Proom — and went to fetch the inkwell and the paper.

‘There’s a letter for you, Anna!’ said Pinny, looking at the postmark and trying not to let the relief show in her voice.

It was Petya, coming to London to greet Niannka and discuss the sale of the jewels, who had told them about the interrupted wedding. Pinny, watching Anna, had seen her turn almost in an instant from the kind of thing one expected to find under a pile of sacking after an earthquake or a famine into a radiant and enchanting girl. Anna, discussing with the delighted Mr Stewart at Aspell’s, the jewellers, what he assured them would be ‘the sale of the century’; Anna, helping her mother buy presents for the other emigrés, treasuring the conviction that it was through Rupert’s good offices that Niannka had been found, was the Anna of the old St Petersburg days with a new glow, a new maturity.

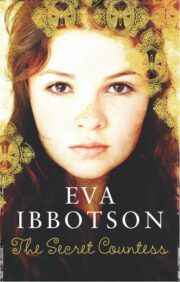

"The Secret Countess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Countess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Countess" друзьям в соцсетях.