The break in the battle comes naturally, when men are too exhausted to do more. They stagger back and rest on their weapons; they gasp for breath. They look, uneasily, at the still ranks of Stanley and Northumberland, and some of them whoop for air or retch blood from their throats.

Richard scans the field beyond the immediate line of battle, holds in his horse, and pats its sweaty neck. He looks across at the Tudor forces and sees that behind the Tudor line, slightly adrift from his troops, is the red dragon standard, and the Beaufort portcullis badge. Henry has become separated from his army; he is standing back with his household guards around him; his army has pushed ahead, away from him. Inexperienced on the battlefield, he has let himself be separated from his troops.

For a moment Richard cannot believe the opportunity that he sees before him, then he gives a harsh laugh. He sees his chance, battlefield luck, given to him by Henry’s momentary pause that has separated him from his army and left him terribly vulnerable. Richard stands up in his stirrups and draws his sword. “York!” he bellows, as if he would summon his brother and his father from their graves. “York! To me!”

His household cavalry leap forwards at the call. They ride in close formation, thundering over the ground, sometimes jumping corpses, sometimes plowing on through them. An outrider gets pulled down, but the main battle, tightly grouped, shoots like an arrow around the back of the Tudor army, who see the danger, and stagger and try to turn, but can do nothing but watch the galloping charge towards their leader. The York horses are flying at Henry Tudor, unstoppable, swords out, lances down, faceless in their sharply pointed helmets, terrifying in their thunderous speed. The Tudor pikemen, seeing the charge, break from their ranks and run backwards, and Richard, seeing them on the run, thinks they are fleeing and bellows again, “York! And England!”

Tudor is down from his horse in a moment-why would he do that, Richard thinks, his breath coming fast, leaning over his horse’s mane, why dismount? – Tudor is running forwards to his pikemen, who dash back to meet him. His sword is drawn, his standard-bearer beside him. Henry is beyond thought, beyond even fear, in this, his first adult battle. He can feel the ground shake as the horses come towards him, they come like a high wave, and he is like a child facing a storm on a beach. He can see Richard bending low in the saddle, his lance out before him, the gleam of the gold circlet on the silver helmet. Henry’s breath comes fast with fear and excitement, and he shouts to the French pikemen, “Now! À moi! À moi!”

They dash back towards Henry and then they turn and drop to their knees and point their pikes upwards. The second rank lean their pikes on their comrades’ shoulders, the third rank, boxed inside, like a human shield for Henry Tudor, point their pikes straight forwards like a wall of daggers at the oncoming horses.

Richard’s cavalry have never seen such a thing done before. No one has ever seen such a thing before in England. They cannot pull up the charge, they cannot turn it. One or two in the center wrench their horses aside, but they just foul the oncoming dash of their neighbors and go down in a chaos of tumbling and screaming and broken bones under the hooves of their own horses. The others plow on, too fast to stop, and fling themselves onto the merciless blades, and the pikemen stagger under the impact, but wedged so tightly: they stay steady.

Richard’s own horse stumbles on a dead man and goes down to its knees. Richard is thrown over its head, staggers to his feet, pulling out his sword. The other knights fling themselves to the ground to attack the pikemen, and the clash of sword on wooden haft, of thrusted blade and broken pike is like hammering at a forge. Richard’s trusted men gather round him in battle order, aiming at the very heart of the battle square, and gradually they start to gain ground. The pikemen in the first rank cannot struggle to their feet with the weight of the others bearing down on them; they are cut down where they kneel. The middle rank fall back against the ferocious attack, they cannot help but give ground; and Henry Tudor, in the center, becomes more and more exposed.

Richard, his sword red with blood, comes nearer and nearer, knowing the battle will be over with Tudor’s death. The two standards are only yards apart, and Richard is gaining ground, fighting his way through a wall of men to Tudor himself. In the corner of his eye he sees the red of the dragon and, furious, he slashes at it and the standard-bearer, William Brandon, in one huge thrust. The standard looks about to fall, and one of Henry’s bodyguard dives forwards, grabs the broken haft, and holds it aloft. Sir John Cheney, a giant of a man, throws himself between Henry and Richard, and Richard slashes out at him too a vicious wound to the throat, and the Tudor knight goes down, knowing that they are defeated, calling, “Fly, sire! Get yourself to safety!” to Henry, as his last words are choked on his own blood.

Henry hears the warning and knows he must turn and run. It is all over for him. And then they hear it. Both Richard and Henry’s heads go up, at the deep, loud rumble of an army at full gallop as the Stanleys’ armies come charging towards them, lances down, pikes out, swords ready, fresh horses tearing towards them as if themselves eager for blood; and as they hit, Richard’s standard-bearer has his legs sliced off from underneath him by a swing from a battle-axe, and Richard wheels around, his sword arm failing him, suddenly fatally weak, in that one moment as he sees four thousand men coming against him, and then he goes down under a flurry of anonymous blows. “Treason!” he shouts. “Treason!”

“A horse!” somebody screams desperately for him. “A horse! A horse! Get the king a horse!”

But the king is already gone.

Sir William Stanley pulls the helmet from Richard’s lolling head, notes that the king’s dark hair is still damp with warm sweat, and leaves the rest of the looting of his fine armor to others. With a pike head he prizes off the golden circlet of kinghood and strides towards Henry Tudor, kneels in the mud, and offers him the crown of England.

Henry Tudor, staggering from the shock, takes it from him with bloodied hands and puts it on his own head.

“God save the king!” bellows Stanley to his army, coming up fresh and untouched, some of them laughing at the battle that they have won in such decisive glory without dirtying their swords. He is the first Englishman to say this to the crowned Henry Tudor, and he will make sure the king remembers it. Lord Thomas Stanley dismounts from his panting horse at the head of his army, which swung the battle, at the last, the very last moment, and smiles at his stepson. “I said I would come.”

“You will be rewarded,” Henry says. He is gray with shock, his face shiny with cold sweat and with someone else’s blood. He looks, but hardly sees, as they strip King Richard’s fine armor and then even his linen and throw his naked body over the back of his limping horse, which hangs its head as if ashamed. “You will all be richly rewarded, who fought with me today.”

They bring the news to me where I am praying, on my knees, in my chapel. I hear the bang of the door and the footsteps on the stone floor, but I don’t turn my head. I open my eyes and keep them fixed on the statue of the crucified Christ, and I wonder if I am about to enter my own agony. “What is the news?” I ask.

Christ looks down at me; I look up at Him. “Give me good news,” I say as much to Him as to the lady who stands behind me.

“Your son has won a great battle,” my lady-in-waiting says tremulously. “He is King of England, acclaimed on the battlefield.”

I gasp for breath. “And Richard the usurper?”

“Dead.”

I meet the eyes of Christ the Lord, and I all but wink at Him. “Thanks be to God,” I say, as if to nod at a fellow plotter. He has done His part. Now I will do mine. I rise to my feet, and she holds out a letter to me, a scrap of paper, from Jasper.

Our boy has won his throne; we can enter our kingdom. We will come to you at once.

I read it again. I have the strange sensation that I have won my heart’s desire and that from this date everything will be different. Everything will be commanded by me.

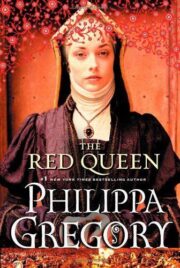

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.