“What?” Henry starts out of a reverie. He is pale, his hands tight on the reins. Jasper can see the strain on his young face, and wonders, not for the first time, if this boy is strong enough to enact the destiny his mother has seen for him.

“I want to ride back the way we have come, and secure safehouses on the way, set some horses ready for us in their stables. I may even go as far as the coast, hire a boat to wait for us …”

Henry turns to his mentor. “You are not leaving me?”

“Son, I could as easily leave my own soul. But I want an escape route for you.”

“For when we lose.”

“If we lose.”

It is a bitter moment for the young man. “You don’t trust Stanley?”

“Not as far as I can throw a rock.”

“And if he does not come to our side, then we will lose?”

“It’s just the numbers,” Jasper says quietly. “King Richard has perhaps twice our army, and we have about two thousand now. If Stanley joins with us, then we have an army of five thousand. Then we are likely to win. But if Stanley joins the king, and his brother with him, then we have an army of two thousand and the king has an army of seven thousand. You could be the bravest knight in all of chivalry and the truest king ever born, but if you go out in battle with two thousand men and face an army of seven thousand, then you are likely to lose.”

Henry nods. “I know it. I am certain that Stanley will prove true to me. My mother swears that he will, and she has never been wrong.”

“I agree. But I would feel better if I knew we could get away if it does go wrong.”

Henry nods. “You’ll come back as soon as you can?”

“Wouldn’t miss it for the world,” Jasper says with his half smile. “Godspeed, Your Grace.”

Henry nods, and tries not to feel a sense of terrible loss as the man who has hardly left his side in the twenty-eight years of his young life turns his horse and canters slowly away, west to Wales.

When Henry’s army sets out the next day, Henry rides at the head of them, smiling to right and left, saying that Jasper has gone to meet new recruits, an army of new recruits, and bring them to Atherstone. The Welshmen and the English who have volunteered are cheered by this, believing the young lord that they have sworn to follow. The Swiss officers are indifferent-they have taught their drills to these soldiers, and it is too late to train more; extra numbers will help, but they are paid to fight anyway, and extra men will divide the spoils into smaller portions. The French convicts, fighting only to earn their freedom and for the chance of spoil, don’t care either way. Henry looks at his troops with his brave smile and feels their terrible indifference.

AUGUST 20, 1485

The Earl of Northumberland, Henry Percy, marches into Richard’s camp at Leicester with his army of three thousand fighting men. He is brought to Richard while the king is eating his dinner under the cloth of state, in his great chair.

“You may sit, dine with me,” Richard says quietly, gesturing to a seat down the table from his own.

Henry Percy beams at the compliment, takes his seat.

“You are ready to ride out tomorrow?”

The earl looks startled. “Tomorrow?”

“Why not?”

“On a Sunday?”

“My brother marched out on an Easter Sunday, and God smiled on his battle. Yes, tomorrow.”

The earl holds out his hands for the server to pour water over his fingers and pat them dry with a towel. Then he breaks some manchet bread and pulls the white soft crumb inside the crunchy crust. “I am sorry, my lord; it has taken me too long to bring my men. They will not be ready to march tomorrow. I had to bring them fast, down hard roads; they are exhausted and are in no state to fight for you.”

Richard gives him a long, slow look from under his dark eyebrows. “You have come all this way to stand to one side and watch?”

“No, my lord. I am sworn to join you when you march out. But if it is to be so soon, tomorrow, I will have to volunteer my men for the rear guard. They cannot lead. They are exhausted.”

Richard smiles as if he knows for a fact that Henry Percy has already promised Henry Tudor that he will sit behind the king and do nothing.

“You shall take up the rear then,” Richard says. “And I shall know myself safe with you there. So.” The king speaks generally to the room, and the heads come up. “Tomorrow morning then, my lords,” Richard says, his voice and his hands quite steady. “Tomorrow morning we will march out and crush this boy.”

SUNDAY, AUGUST 21, 1485

Henry waits as long as he dares, waits for Jasper to come back to him. While he waits, he orders the pikemen to practice their drill. It is a new procedure, introduced by the Swiss against the formidable Burgundian cavalry only nine years earlier, and taught by the Swiss officers to the unruly French conscripts; but by steady practice, they have perfected it.

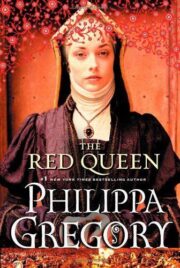

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.