On the twenty-first of April my journey to France began. During the last few years I have often thought of my mother when she said goodbye to me. She knew it was the last time she would hold me in her arms, the last time she would kiss me. No doubt words came into her mind.

Remember this. Don’t do that. Surely she had said it all to me in her icy bedroom; but knowing me, she would realise that I had forgotten half of it by now. In any case I should have heard little of what she said to me. Now I knew she was praying silently to God and the Saints, asking them to guard me. She saw me as a helpless child wandering in the jungle.

“My dearest child,” she whispered; and suddenly I did not want to leave her. This was my home. I wanted to stay in it-even if it did mean lessons and painful hairstyles and lectures in a cold bedroom. I should not be fifteen until November and suddenly I felt very young and inexperienced. I wanted to plead to be allowed to stay at home for a little longer, but Monsieur de Durfort’s magnificent carriages were waiting; Kaunitz was looking impatient and relieved that all the bargaining was over. Only my mother was sad and I wondered if I could be alone with her and beg to be allowed to stay. But of course I could not. Much as she loved me she would never allow my whims to interfere with state affairs. It was a state affair. The thought made me want to laugh—and it pleased me too. I really was a very important person.

“Goodbye, my dearest child. I shall write to you regularly. It will be as though I am with you.”

“Yes, Mamma.”

“We shall be apart but I shall never cease to think of you until I die. Love me always. It is the only thing that can console me.”

And then I was getting into the carriage with Joseph, who was to accompany me for the first day. I had had little to do with Joseph, who was so much older and had become so important now that he was Emperor and co-ruler with my mother. He was kind, but because of my mood I found his pomposity irritating, and all the time he gave me advice to which I did not want to listen. I wanted to think about my little dogs, which the servants had assured me they would care for.

When we passed the Schonbrunn Palace I looked at the yellow walls and the green shutters and remembered how Caroline, Ferdinand, Max and I used to watch the older ones perform their plays, operas and ballets.

I remembered how the servants used to bring refreshments to us in the gardens—lemonade, which my mother thought was good for us, and little Viennese cakes covered with cream.

Before I left, my mother had given me a packet of papers which she said I was to read regularly. I had glanced at them and saw that they contained rules and regulations which she had already given me during our talks. I would read them later, I promised myself. I wanted now to think about the old times—the pleasantness of the days before Caroline and Maria Amalia had been so unhappy. I glanced at Joseph, who had had his own tragedies, and thought he seemed to have recovered as he sat there so serenely against the gorgeous satin upholstery.

“Always remember you are a German…. I wanted to yawn. Joseph in his laboured way was trying to impress upon me the importance of my marriage. Did I realise that my retinue consisted of one hundred and thirty-two persons? Yes, Joseph, I had heard it all before.

“Ladies-in-waiting, your servants, your hairdressers, dressmakers, secretaries, surgeons, pages, furriers, chaplains, cooks and so on.

Your grand postmaster the Prince of Paar has thirty-four subordinates.”

“Yes, Joseph, it is a great number.”

“It is not to be supposed that we should allow the French to think that we cannot send you off in a style to match their own. Did you know that we are using three hundred and seventy-six horses and that these horses have to be changed four or five times a day?”

“No, Joseph. But now you have told me.”

“You should know these things. Twenty thousand horses have been placed along the road from Vienna to Strasbourg to convey you and your retinue there.”

“It is a great number.”

I wished that he had talked to me more of his marriage and had warned me what to expect of mine. I was bored by these figures, and all the time I was fighting my desire to cry.

At Moick, which we reached after eight hours’ driving, we stayed at the Benedictine convent, where the scholars per formed an opera for us. It was a bore. I felt very sleepy, and as I kept thinking of the previous night, which I had spent in my mother’s bedroom in the Hofburg, I felt I wanted to cry for the comfort she could give me. For oddly enough, in spite of the lectures, she had comforted me; with out knowing it I had felt that while she was there, omnipotent and omniscient, I was safe because all her care was for me.

Joseph left me the next day and I was not sorry. He was a good brother who loved me but his conversation made me so tired and I always found it difficult to concentrate at the best of times.

What a long journey! The Princess of Paar shared my carriage and tried to comfort me by talking of the wonders of Versailles and what a brilliant future lay before me. To Enns, to Lambach, on to Nymphenburg. At Giinsburg we rested for two days with my father’s sister. Princess Charlotte I had vague memories of her at Schonbrunn for she had at one time been a member of our household. My father had been very fond of her and they used to take long walks together, but my mother resented her presence. Perhaps she resented anyone of whom my father was fond; and eventually Charlotte retired to Remiremont, where she became the Abbess. She talked lovingly of my father and I went with her to distribute food to the poor, which was a change from all the banquets and balls.

We crossed the Black Forest and came to the Abbey of Schiittern, where I was visited by the Comte de Noailles who was to be my guardian. He was old and very proud of the duty which had been entrusted to him by his friend the Due de Choiseul. I thought he was a vain old fellow and I was not sure whether I liked him. He did not stay long with me for there arose a difficulty about the ceremony which lay before me. It was again a matter of whose names should come first on a document.

Prince Starhemburg, who was going to hand me formally over to the French, was in a great passion about this; and so was the Comte de Noailles.

I felt very sad that night because I knew it was going to be my last on German soil. I suddenly found myself crying bitterly in the arms of the Princess of Paar and saying over and over again: “I shall never see my mother again.”

That day a letter had reached me from her. She must have sat down and written it as soon as I left; and I knew that she had written it in tears. Snatches of it come back to me now:

My dear child, you are now where Providence has placed you. Even if one were to think no more of the greatness of your position, you are the happiest of your brothers and sisters. You will find a tender father who will be at the same time your friend. Have every confidence in him. Love him and be submissive to him. I do not speak of the Dauphin. You know my delicacy on that subject. A wife is subject to her husband in all things and you should have no other aim than to please him and do his will. The only real happiness in this world comes through a happy marriage. I can say this from experience. And all depends on the woman, who should be willing, gentle and able to amuse. “

I read and re-read that letter. That night it was my greatest comfort.

The next day I would pass into my new country;

I would say goodbye to so many of the people who had accompanied me so far. There was so much I had to learn, so much which would be expected of me—and all I could do was cry for my mother.

“I shall never see her again,” I murmured into my pillow.

The Bewildered Bride

The Golden Age will be born from such a union, and under the happy rule of Mane Antoinette and Louis-Auguste our nephews will see the continuation of the happiness we enjoy under Louis the Well-Beloved.

On the no-man’s land of a sandbank in the middle of the Rhine a building had been erected, and in this was to take place the ceremony of the Remise. The Princess of Paar had impressed on me that this was the most important ceremony so far, for during it I should cease to be Austrian. I was to walk into that building on one side as an Austrian Archduchess and emerge on the other as a French Dauphine.

It was not a very impressive building, for it had been hastily constructed; it would be used for this purpose only and that would be an end of it. Once on the island I was led into a kind of antechamber where my women stripped me of all my clothes, and I felt so wretched standing there naked before them all that I had to think of my mother at her most stern to prevent myself breaking into sobs. I put my hand up to the chain necklace which I had worn for so many years, as though I were trying to hide it. But I could not save it. The poor thing was Austrian and therefore had to come off.

I was shivering as they dressed me in my French clothes, but I could not help noticing that they were finer than anything I had had in Austria and this lifted my spirits. Clothes meant a great deal to me and I never lost my excitement for a new material, a new fashion or a diamond. When I was dressed I was taken to the Prince Starhemburg who was waiting for me; he held my hand firmly and led me into the hall

which formed the centre of this building. It seemed large after the little antechamber, and in the centre was a table which was covered with a crimson velvet cloth. Prince Starhemburg referred to this room as the Salon de Remise, and he pointed out that the table symbolised the frontier between my old country and my new.

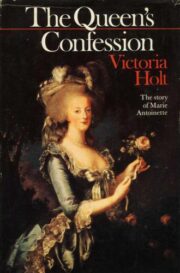

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.