Magda stopped suddenly, leaned over the side of the bed, and was sick on the floor.

Nina was ready to agree to anything just to get Magda to calm down and go to sleep.

3. THE ANNIVERSARY OF THE BOLSHEVIK REVOLUTION

The city was shrouded in a damp mist. On every side, trucks rattled past, and soldiers marched along wordlessly in felt helmets with the ear flaps down. Armored cars crouched darkly in the lanes and alleyways, and from time to time, the sound of a horse’s whinny or the hollow echo of hooves could be heard as the Red Cavalry prepared for the parade.

Nina walked along in the crowd, clutching Magda’s camera in its case to her chest. Magda had only one roll of film left and had instructed Nina to guard it with her life.

Everybody was gawping at Nina’s ridiculous coat. One little girl was so distracted by the sight that she dropped her bunch of chrysanthemums on the ground.

Her mother immediately fetched her a clip on the back of the head. “Look after those flowers,” she scolded. “What are you going to wave at the parade if you lose them?”

At the approach to Red Square, all was excitement and anticipation as if before a battle. Huge banners and portraits of Soviet leaders swayed in the swirling mist; military instructors made their rounds of the workers’ brigades, giving instructions about the order of procession, while the shivering men hopped from foot to foot in an effort to keep warm.

Nina was also shivering, but more from anxiety than cold. She was certain that at any minute, she would be accosted by a policeman who would ask her to explain just how she had managed to get ahold of a foreigner’s pass for the tribune.

But all went well. At the Iversky Gates, Nina showed her pass and walked out onto Red Square where the unpaved ground had frozen hard during the night.

A scarlet flag fluttered above the Kremlin wall. On the ancient spires of the Kremlin towers, the golden Imperial eagles, still untouched by the Bolsheviks, gleamed faintly through the mist. At the other end of the square, on the building of the State Department Store, GUM, an enormous canvas with a portrait of Lenin with his bulbous forehead and bourgeois suit and tie was flapping and billowing in the wind. As vast, mighty, and eternal as an Egyptian pharaoh, he looked down sadly at his own mausoleum built in the shape of a truncated pyramid. It was a strange quirk of history that twentieth-century Russia had revived the customs of Ancient Egypt.

Nina mounted the tribune and sat down on a wooden seat in the corner. Nobody seemed to be paying her any attention.

Gradually, the tribune filled up with foreign guests: Europeans and Americans, Indians and Arabs, but Chinese above all. Nina even saw some familiar faces among them. They were the men with whom she had traveled across the Gobi Desert. They appeared quite unsurprised by Nina’s presence on the tribune.

The foreign guests kept up a stream of lively chatter, blowing on their frozen fingers and trying to find a good position from which to take photographs and film the parade. A tall, round-shouldered man wearing a pince-nez moved between them, switching between various foreign languages to greet his esteemed guests and ask if he could do anything to help them.

“And who are you?” he asked amiably when he came to Nina.

She acted as if she had not understood the question.

The man in the pince-nez stamped around a little longer before sitting down on the bench behind Nina.

“Who is that?” she heard him ask somebody. “The woman in the red coat?”

“I don’t know, Comrade Alov,” said a young voice. “I don’t recognize her.”

“Well, find out then,” Nina heard Alov say.

He was almost certainly an agent from the OGPU, and Nina cursed herself for having agreed so thoughtlessly to Magda’s request. What if this Alov were to ask for her documents? Or what if one of the Chinese guests told him that she was Russian?

Just then, some members of the Soviet government came out onto their tribune, and all the foreigners jumped to their feet and began to take photographs. Nina had no idea who they were, but she took some pictures too just in case they might come in useful to Magda. It was strange how small and unimposing they all looked; in their military-style suits, they resembled a crowd of provincial clerks dressed up as war heroes.

A moment later, a woman holding a folder rushed up to Alov and began to whisper to him. Nina could make out the words “Trotsky” and “spontaneous demonstration.”

“Damn!” muttered Alov. Running down the steps, he disappeared into the crowd of soldiers standing in the cordoned off area.

Nina breathed a sigh of relief. She decided to take a few more photographs and leave while the going was good.

The bells of the Spassky Tower began to peal, and the roar of thousands of voices went up from the streets around Red Square. “Hurra-a-ah! Hurra-a-ah!”

To the strains of the “Internationale,” the Soviet anthem, the first columns of demonstrators began to file out onto the square.

Announcements blared from the loudspeakers fixed to the lampposts around the square:

“Now, at the time of this celebration, greater than any in the course of human history, our thoughts are of our great leader, Lenin, who led the victorious troops of workers in their fearless attack on the bastions of capitalism!”

The government representatives smiled, saluted, and waved to the demonstrators with their leather-gloved palms.

Then a column of young people came level with the mausoleum—students, apparently. They stopped, and a moment later, a banner unfurled above their heads emblazoned with the words, “Down with Stalin!”

The orchestra fell silent, and a deathly hush descended on the square. All that could be heard was the chirruping of the sparrows that had flown in to peck at the horse manure.

“Long Live Trotsky!” shouted a young man’s voice. “Down with opportunism and party separatism!”

His comrades sent up a ragged cheer.

A moment later, policemen came running in on the demonstrators from all sides.

Nina raised her camera and took a photograph. The foreigners around her were also snapping away.

“Stop! No photographs!” shouted a voice, and Alov came bounding up the stairs of the tribune two steps at a time.

His gaze fell on Nina. “I said no photographs!” he barked and snatched away her camera.

“What are you doing?” gasped Nina, forgetting that she was not supposed to speak Russian. “Give that back!”

“So, you’re Russian, are you?” Alov grabbed Nina by the shoulder. “How did you get onto the tribune? And who are you, anyway?”

Nina broke free of his grasp, beside herself with fear, and rushed down the steps.

“Stop that woman!” roared Alov, but the police were too busy to apprehend Nina. A fierce struggle between the police and demonstrators had broken out in front of the mausoleum.

Nina wandered about the city all day, at a loss as to what to do. She could not go back to her hotel room—the OGPU had almost certainly worked out already who she was and where she lived. For them, an emigrant who had returned to Russia to take pictures of a pro-Trotsky demonstration could only be a spy, and Nina would be arrested without fail.

She felt guilty about Magda. How would she manage now without her camera or her interpreter? Moreover, Alov was almost certain to question her about Nina. Nina hoped fervently that Magda herself would not be suspected of espionage.

Nina knew that she had to get away from the capital. She decided to buy a ticket to a city as far away from Moscow as she could afford and then work out how to get to Vladivostok and then to China. But at the station, she was told that all the tickets for the next few months had been sold.

Nina walked out of the station and boarded the first tram that came along. Her mind was racing. Where could she go now? Where could she spend the night? On a park bench? Even if she found a place to shelter, she would, in any case, get through all the money she had managed to save in less than a month. And what then?

“Fares, please, comrades,” said the conductor, pushing his way through the tightly packed passengers.

Nina reached into her pocket and froze. Her purse had disappeared.

“Are you going to buy a ticket or not?” asked the conductor.

“My purse has been stolen,” Nina said.

The conductor grabbed her roughly by the collar. “Off the tram with you. Look at you, dressed up to the nines in velvet without a kopeck to pay for your ticket.”

“The lady’s had a fight with her lover, I reckon,” grinned a blue-eyed soldier standing beside Nina. “And he sent her packing, skint.”

The passengers began to laugh.

Nina pushed her way to the door and, as the tram slowed down, jumped from the footplate out into the muddy street.

It was already dark. The howls of chained dogs in nearby yards echoed in the night air. The street lights were not lit, and the only glimmer of light came from the open door of a small church nearby.

So, that’s that, thought Nina. There’s no way I’ll get back to Vladivastok or to China. I’ll have to sell my coat tomorrow to eat, and then I’ll throw myself in the Moscow River.

She stood for a moment, looking distractedly about her. Then she headed toward the church. Surely she could find shelter there?

The church was almost empty. There was only a server in felt boots topping off the icon lamps with oil.

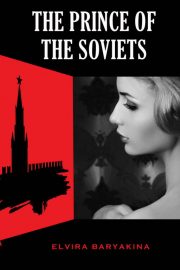

"The Prince of the Soviets" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince of the Soviets". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince of the Soviets" друзьям в соцсетях.