“We’ll get you one when we get back to Moscow,” Klim said.

“Can you get gas masks for horses?”

“I expect so. Go to sleep now.”

“What about giraffes? Elkin made me a giraffe rocking horse. I need to get a gas mask for it too.”

Elkin seems to have been getting all sorts of ideas, Klim thought. Well, I suppose he can dream.

Klim was already picturing the scenario to himself—the seduction of Mrs. Reich. It would be like the classic plot of a Russian novel. A high society lady dreams of leaving her rich husband, and while touring from city to city in the South, she meets an old acquaintance with whom she has previously been in love. They both know the affair can’t last—the holidays will end, and they will go back to their own social circles. But why should they deny themselves the pleasure when fortune is offering them this wonderful opportunity never to be repeated?

Gradually, the voices outside began to die down. The locals were starting to leave for their village and the guests to go off to their bedrooms.

At last, Kitty was asleep. Klim tucked the blanket around her and went out into the corridor. He wandered around the house for some time before he found Nina out on the terrace. She was lying in a hammock between two pillars, rocking herself gently with one foot.

“You can go to your room now,” Klim told her.

Nina sat up hurriedly and began to pull out the pins that had worked themselves loose from her hair.

“Yes, just a minute…” she began but then patted the hammock beside her. “Come and sit. We need to talk.”

“What about?”

“About us.”

The hammock stretched under Klim’s weight, forcing Nina closer to him.

This is it, he thought. This was what he would travel to the ends of the earth to feel—the touch of her thigh, the warmth of her body, which he could feel through two layers of clothes.

“Will you let me explain everything to you?” asked Nina.

Klim put his arms around her and pressed his lips to hers. “Tell me later.”

Nina wound her arms around Klim’s neck, and the giraffe pendant dug painfully into his chest.

“Take this thing off,” he said.

Nina pulled the pendant off over her head and threw it to the floor without a glance.

In his mind, Klim was already gathering her skirt in his hands, kissing her voluptuous breasts, gripping her tightly by her slender wrist to hold her completely in his power, to give her no chance to escape.

He pushed her back onto the hammock, which swayed precariously under them.

“We’ll fall out of here in a minute,” Nina laughed.

Klim bent over her. “If we do, it would be a wonderful illustration of the collapse of contemporary morals.”

Suddenly, a ray of light swept over them, and the cockatoo came fluttering overhead.

“Court martial!” it shrieked, landing on the terrace railing.

Klim raised his head to see Gloria in the doorway, a lantern in her hand. Surrounded by wreaths of pipe smoke, she seemed to be emerging from a cloud.

“Why have you left your daughter alone?” Gloria scolded Nina. “Go back to your room this minute!”

Shamefaced, Nina stood up and began to fasten the buttons of her dress. There was a crunching noise under her foot. She looked down and saw that she had stood on the Elkin’s giraffe figurine.

Gloria shuffled up to Klim and handed him a telegram envelope.

“Here,” she said. “This came yesterday. I forgot to give it to you.”

It was a message from Seibert:

Come Moscow immediately stop matter of life and death stop ticket reserved

Nina looked at Klim in alarm.

“What is it?” she asked.

He was silent for a minute, gathering his thoughts.

“Take no prisoners!” the squawk of the cockatoo came out of the dark.

“A friend of mine is in trouble,” said Klim. “He needs help, so Kitty and I will have to go back to Moscow tomorrow evening.”

Galina once told me I was the only gentleman of her acquaintance. I fear she was badly mistaken.

A true gentleman should be gallant and chivalrous and never abandon a damsel in distress, especially if that distress takes the form of a desperate desire to kiss him.

When I explained to Nina that I had to return to Moscow out of duty to a friend, she tried to talk me out of it. “Stay here! After all, you love me, don’t you?”

Then, with unforgivable rudeness, I announced that I love my wife—that is the old Nina. Now, she is another man’s spouse. It seems she sees marriage rather like a joint stock company: if her husband doesn’t put in his share in time, she begins to shift her assets and make investments elsewhere. Alas, that isn’t what I want at all.

This made Nina angry.

“You was the one who kissed me first!” she reminded me.

A gentleman in my place would have said something about her charms or about the power of Cupid’s arrow or something else appropriate, but instead, I did something outrageous. I told her that I had had a choice: either to hear details of all her infidelities or to pay Oscar back in kind and to cuckold him just as he had cuckolded me. The second course seemed to me the more interesting one.

“But I told you,” Nina cried, “I’m not going back to Reich!”

“Well, that’s a shame,” I said. “Of course, you could stay with Elkin and be the wife of a country blacksmith for a while, but I imagine that wouldn’t be a very good deal for you.”

Then all hell broke loose. Nina is not only passionate in matters of love; she has a fearsome temper too. She poured such a torrent of abuse at me that I’m afraid I’ll never manage to clear my name.

I was listening respectfully to all this when she suddenly stopped mid-flow and announced that in any case, I would not escape her. She would get ahold of a ticket and come back to Moscow after me, sinner that I am.

Now, I am full of curiosity about what she is planning to do. After all, I haven’t had the holiday I was hoping for, so I’ll have to find my amusement in some other way.

I think I have hit on the right way to handle my relations with Nina. We need less drama, more pragmatism, and a sensible approach to our affairs. We should behave like relatives with shared family concerns. After all, I did want Nina to take a role in bringing up Kitty. If she can get herself settled in Moscow, then we can be on friendly terms.

I am very grateful to Seibert for whisking me away from Koktebel in the nick of time. I came very close to crossing a line I must never cross.

25. THE HOUSING PROBLEM

Alov was woken by the rattle of the lid on the coffee pot.

“Dunya, my dear,” he heard Valakhov saying on the other side of the dresser, “do you know why it is that only twenty-five percent of the overall membership of the Young Communist League are women? It’s because they have to stop taking part in public life after they’re married. Look at you, for instance. What are you doing now? Making breakfast for your husband. But you could be using that time to go to a party meeting.”

Dunya said nothing. The only sound that came from behind the dresser was the measured tapping of her knife against the breadboard as she cut something.

“Everyday domestic chores will turn even the most principled women into empty-headed housewives,” Valakhov continued. “With your talent, you should be acting in movies, and you’re wasting the best years making sandwiches and washing dishes.”

Alov sat up in bed. I’ll smash his face one of these days, I swear! he thought for the thousandth time. But he knew it was impossible. Valakhov was the star of the OGPU wrestling team while Alov was unable to manage even a single pull-up on the crossbar.

“Get some portraits done by a photographer and give them to me,” Valakhov said eagerly. “One of my friends is a director, and as it happens, he’s looking for a girl just like you.”

“Don’t listen to him!” Alov barked, poking his head around the side of the dresser. “It’s all lies!”

Dunya was bustling about in their “kitchen,” a small area next to the window sill. On the sill stood two primus stoves and a breadboard with shelves underneath for storing food. The top shelf was for Dunya and Alov, and the bottom shelf for Valakhov.

Dunya thrust a sandwich and an enamel mug of ersatz coffee under her husband’s nose. “Here’s your breakfast.”

Valakhov was lying on the sofa, his muscular white arms flung behind his head. Alov stared at Valakhov’s faded underpants with disgust. What kind of man walked about in his underwear in front of another man’s wife?

“Good morning to you!” Valakhov waved cheerily to him. “What’s the health forecast today then? You were coughing so loudly last night you just about deafened me. Seriously, it was louder than artillery training.”

“Knock it off,” spat Alov, seething with impotent rage.

Dunya fastened a white headscarf around her head, planted a kiss on Alov’s unshaven cheek, and ran off.

Every day, she went out to a theatrical agency looking for work. Sometimes, she would land a role and bring back a fee of five rubles. For children’s matinees, she would get three rubles, and for pageants, no more than one and a half.

Valakhov knew that Dunya would do anything for a genuine role and exploited the fact shamelessly. And if Alov made any objection, he would just mock him.

“Dunya, my dear, it looks as if your husband wants to keep you locked away between these four walls—or should I say two walls?”

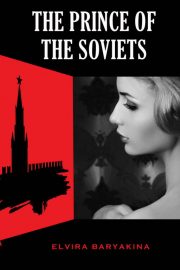

"The Prince of the Soviets" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince of the Soviets". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince of the Soviets" друзьям в соцсетях.