“How can you be an idiot… when there’s a Hermann Göring Strasse right across the street from Adi’s spectacular Chancellery?”

“Don’t tell me you like Speer’s barrack-Greek buildings?”

“They please the Führer.”

“Speer! If I see one more of his buildings with a golden spread-eagle a hundred feet high… really! Better a golden spread-crotch, male or female. And all his tall bronze doors up to the ceiling that dwarf us. But I have more important things in common with the Führer. We’ve always wanted to get rid of the old Bismarckian Reich. Military leadership, we agree, is Germany’s new elite.”

“But you never heard voices. Voices told the Führer to save Germany.”

“Dear girl, those voices were induced by the temporary blindness the Führer was afflicted with as a gassed corporal in the hospital during the Great War. They were good practical voices, and I’m able to hear them through him.”

“Is that why Adi gave you the Air force?”

Hermie made a fast tight frown. “I cannot afford to put all our air power on the front lines. We never have enough reserves. Those damn Americans always have supplies. Roosevelt calls for a production of four thousand airplanes a month. Bombing us is America’s way to lift up the morale of Russia.”

“Pfui. You’re the one who has the great pilots, Hermie.”

“I learned too late that piano players make the best pilots because they pound the keys, stamp pedals, flip over music sheets without losing a beat. Vons make the worse, single minded idiots who are pragmatic and slow.”

“Yes, intellectuals are dangerous for Germany. And for Adi’s genius,” I added.

“Aber! Aber! It’s the practical that wins. We drop balls of silver paper.”

“Why is that?” I asked.

“Silver muddles up their radar. And that is my idea. Though the terrifying sirens on our wing-tip Stuka dive-bombers are the Führer’s suggestion.”

“That’s why Charles Lindbergh said that the Luftwaffe was the strongest Air Force in the world?” Hermie had to know that I kept up with the news.

“But Lindbergh was skeptical in the beginning. He once asked me why a man who didn’t rise above a corporal could tell us how to fight. I replied to Herr Lindbergh that if Adolf Hitler had decided to become a career pilot, he—Lindbergh—would not have been the first to cross the Atlantic. And soon, of course, he realized our Führer was a great man, so we gave Charlie the German Cross of the German Eagle, higher than anything given to an auslander.” Hermie slapped his knee in anger. “But none of us knew it was the German factories that would let us down. No creative energy comes from the industrial sector. The results of our disarmament after the Versailles Treaty. For years we didn’t produce any war equipment. Thus our workers have no skill and no proper machines.”

“But that isn’t your fault,” I said.

“I’m aware that nothing is my fault. But who would have guessed that we’d have to use the Autobahn as a runway strip, even hotel ski runs and cattle paths? Our paratroopers are landing on the backs of heifers. But I’m happy to say they paint swastikas on those cows as soon as they land.”

“Can’t you be more cheerful?”

Hermie began to chant,

“There was a young girl from Berlin

Who peddled her sin, sin by sin

Inspired, I guess

By the obvious mess

Of Krebs, Rommel and Hess.”

“That’s not cheerful. Don’t talk like you can’t do anything more. You know Adi hates that.”

“I do everything I can to raise spirits. Taught my men about baseball, a game I hate. Told them all about that great home run hitter, Ted Williams, who is now a fighter pilot. I tell my men they’re flying against Ted Williams.”

“You and your pilots are still fighting this Ted.”

“You’re entirely too sweet. It will get you nowhere. Certainly not in politics. Such accommodations are perhaps acceptable in bed. Will you get a special romp tonight?”

“Just because it’s his birthday? What kind of philosophy is that?”

“My dear, there are more things in this world than are dreamed of in any philosophy. Remember that Roman Emperor who nailed laws at the very top of the town walls so that his citizens couldn’t read them?” Rubbing a palm to his cheek, Hermie’s aching jaw is so much a part of him that the gesture was automatic and his face didn’t twitch in pain. But he saw that I noticed.

“A stone in my salivary gland. My saliva’s too thick and I use a Chinese spoon to unplug myself.”

“Surely Dr. Morell can help that.”

“It’s entirely too uninteresting for Dr. Morell. On to more serious things. Do you know, there’s a museum in Mussolini’s Vatican that stockpiles phalluses from every statue ever created in Italy.”

“That’s somehow rather comforting.” Perhaps all the statues of Adi, his wondrous manhood tucked beneath his uniform, would be preserved forever, at least in Italy.

“Ach, there are times when I miss going to the movies,” Hermie said, trying to forget his longing for stored phalluses.

“You miss those awful war films put out by Goebbels?”

“Not low artistic junk. Bomber Wing Lutzow. Goebbels emptied the theatres with that one… volkstümlich! I miss The Blue Angel which Hugenberg stupidly had to ban as un-German. What’s un-German about lust? It’s depressing to me that The Jazz Singer, that marvelous talkie, opened in US in 1927. Sound came slowly to Berlin… still we have Wiener Blut with all its glorious waltzes. And Der Gasmann is a pleasing comedy.”

“Comedies depress me, Hermie.”

“So, Evie, it’s tragedy you like. Well, what’s it going to be tonight on his birthday? He’s often reflective at this time, and there’s no worse depression for the Führer than when he returns to himself.”

“What do you mean?”

Hermie sang: “In der Nacht ist Mensch nicht gern allein… in the dark, a Führer has no wish to be by himself.”

“He’ll be with me in the dark.”

“So that perineum of yours is finally going to get it?”

“I don’t even know what a perineum is.”

“You’re reading too much Tolstoy. Tolstoy is a sedition manual.”

“For all your artistic sensibilities, you can sometimes be crude.” But I giggled. “You know, Hermie, as much as I want it, it can never leave him. Such citadels, his thighs, such columns.”

“Yes… yes. I’ve heard all that. But during war, he can partake what is common for once. Perhaps Dr. Kunz’s dentist chair with all its amusing adjustable heights.”

“You mustn’t speak like that.”

“Evie, enjoy the war. Because the peace will be horrific.”

“Peace with Adi will be just as enjoyable.”

“Do you really believe that, sweet girl?”

“As long as we all have the Führer.”

Hermie lit a Dutch Rittmeester cigar, determined to take his own advice and enjoy the war. It was an extra large cigar that was made for his importance and girth. “Victory” was written in ink on the cigar, and he told me that’s the only way he can smoke in the Führer’s presence. Smoke was mandated as bad for people as well as for Blondi and her pups. I’m furiously trying to quit.

(Adi says: “Napoleon hated smoking, too, and once ordered a smoking ban through out the country. My stupid generals think smoking is good for the war because it helps soldiers be steady in battle. Keitel keeps complaining that we need more cigarettes, more, infinitely more.”)

Hermie’s family goes back to the Carolingians, people who were mostly beheaded. He feels justified in wearing his black fur cap with plumes.

“You, the leader of the Luftwaffe, wearing a bullfighter’s cummerbund and plumes.”

“You think the supply sergeant will notice?”

“I notice. What are you trying to do?”

“Look like a soldier in the days of old Fred the Great, very orotund. At any rate, you know the Führer lets senior officers use their own judgment about such matters as personal detail.”

“But the Führer has simple tastes.”

“Evie, it takes a lot of money to keep the Führer humble.”

“You would do well to be so humble.”

“Don’t I pay five Reichsmarks to any one bringing me a new joke about myself?” He strutted for me in his enormous pants of soft leather, puffing out his chest under a hunting coat specially made by Stechbarth of Berlin with its green velvet collar and pleated back that allowed him to get even fatter. He spouted a German proverb: “Mitgegangen, mitgefangen, mitgehangen… fought together, captured together, hanged together.”

“You’re supposed to be cheering me up.”

Hermie went into his Roosevelt mimic, picking up the special phone that he ordered installed, a large telephone that he could dial with his mace instead of a pen. “Baw-lin? Washington calling. We don’t like waw. Eleanor and I say waw is Germany’s fawlt.”

Roosevelt didn’t sound so fearsome that way, and I laughed.

“There’s a delicious joke going around Berlin,” Hermie announced happily.

“Tell me! Tell me,” I pleaded.

“In the war room, Adolf Hitler asks his generals if it’s noon yet. General Mohnke answers by saying that if the Führer wants it to be noon, then it’s noon.”

I gave a wooly smile edged in uncertainty. It wasn’t something to laugh at, only to admire. What glorious powers Mein Führer has, even able to will time itself.

“Behind his back, they call him der Furor. Now that’s something to be proud of. Oh, I love him as much as you, Evie. He’s my conscience. But he’s not my body. Nor would he want to be. I bow to biology.” He patted the paunch between his legs and began to sing a little ditty:

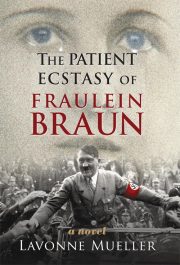

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.