Adi had long desired the Plague in Florence, so he made light of Musso’s quip. “It’s the Third that will get you Shirley temple.” He handed Musso three bananas and two oranges. To prove the extent of his good nature, Adi went to the kitchen himself and returned with a basket of plums, pears, peaches, apricots and seven different kinds of mustard. It was important that the Fascist State stay loyal to him.

“Are you bothered that the press calls you Germany’s Mussolini?” Musso asked.

“Not when you’re called Italy’s Hitler.”

Both men chuckled with an edge of mistrust.

With gravy sliding down his chin, Musso bowed and told me I must come to the German Embassy in Rome. He didn’t bend at the waist but all over like a cucumber. He put his plump sweaty hand on mine. “Von Mackensen, your Ambassador there, would be proud to display a beautiful German woman.”

“I’ve been to Venice. That’s all the Rome I need.” I took his hand away from mine and placed it firmly on a hairy peach. Didn’t Goebbels tell me that most Italian officers are still loyal to the King not the Dictator?

“Venice?” Musso asked. “How did I miss you? Was that during my launch on Greece?”

Adi had no intention of explaining my invisibility though the Duce was free to parade his mistress, Clara Petacci, all around. It was the Führer who projected no private life. Adi was more intent on why Musso didn’t come down hard on the Anglophiles and Americanophile tendencies in Italy. The whole Greece thing was a mistake with the Italians being pushed back into Albania. Adi had to get them out of that mess as he had a fondness for the “fat one,” meeting him for conferences at the Brenner Pass where both their trains were shunted into a specially made railway tunnel.

“Remember, Greece rose to great cultural glory by Aryan settlers,” Goebbels boasted.

Goebbels was dismissive of Musso saying the Duce was only a translation. I don’t quite know what that means. But since he and Musso have written novels—both worthless ones I’m told—perhaps Goebbels believed that Musso could only be read through another’s words.

“I have eight million bayonets. Eight million bayonets! Still, I appreciate your German parachute divisions for the Crete attack. How happy it is to see that Germany has left the Treaty of Versailles behind at last.” Placing his leg closer to mine beneath the table, Musso patted my ankle with the padded soles on his shoes. It was true. He had added several inches to his height. The Italians! No wonder their silly pianos have 12 pedals. Pulling away from his high heels, I excused myself to see about the after dinner tea and coffee.

I had to sit through some boring dinners with Musso watching him eat a pear in that awful Italian manner with his knife making one long curling wreath of skin. I’m grateful that he provided a valuable hint, telling Adi to always jump from his car before it came to a complete stop and to spring immediately into the nearest shelter. The Duce learned this technique from his war in Abyssinia, and it saved the Führer’s life when crazy Commies or jealous Catholics waited with knives for his Mercedes to stop only to find there was nothing to kill but a driver (the driver’s life, of course, being worthless).

Other hints from the Duce were not practical like his suggestion that German women could lean from their windows and pour scalding oil over American and Russian tanks like the women of Eger Castle in northern Hungary did in an earlier time when the Turks stormed into their country.

Certainly Adi was loyal to Musso by rescuing him from that hotel in the highest peak of the Italian Apennines with SS commandos and the Fallschirmjaeger. Adi was repaying Musso for not being bought off by the French with food, iron, coal and petroleum. “For entering the war,” Musso stated honestly, “I need a few thousand dead so I can sit down at the peace table as a belligerent.”

But these days, it’s hard to make fun of Musso. First he was sent into exile on the Isle of Maddalena. And we think now he’s probably been captured maybe killed. Different messengers coming into the Bunker report a rumor that Musso was hanged upside down in a gas station by the partisans. Adi released two sterilized fortune-tellers from Ravensbrück to tell us if the Musso rumor is true. But they said without some personal knowledge of the Italian temperament, they couldn’t give a valid answer.

Adi declared he would never let himself be captured like Musso, put in a cage and dragged through the streets of Berlin, but the worthless gypsies should be.

I have never liked gypsy fortunetellers as they have coarse hair, knotted calves, and skinny calloused fingers. What could they possibly know that the Führer doesn’t know?

Latrine rumors grow in abundance, and it’s not healthy for me to concentrate on them. I try to turn my thoughts to more worthwhile things like making the Bunker more pleasing and trying to understand why so many soldiers here have different names in Munich.

Proving difficult are the floors. To give an old world stone look, I have Sergeant Scholz, with eyebrows like brambles, rub them with light gray paint so that only part of the concrete shows through. But with the Goebbels children biking and jumping all around, it’s useless. Tricycles make too many black streaks.

Nothing but dull duty rosters and smelly gas masks are on most of the walls except for that awful life size oil portrait of Frederick the Great that Adi has in his apartment, shipping it here on his private four engine Focke-Wulf Condor airplane, the old pasty king posed upright in a seat as the only passenger. Every night after dinner, Adi sits in front of that portrait, and I perch quietly beside them both, listening in on silent thoughts communicated between two great men. Then I read aloud from his favorite book, History of Frederick the Great, but only the chapter that tells about the turning point of the Seven Years War in 1700-and-something when a miracle happened and Prussia was saved at the last minute.

5

“ANYONE WHO SAYS THE WAR IS LOST WILL BE TREATED AS A TRAITOR,” Adi declares.

With a nervous outburst, he tells me in a very agitated tone that when he shaves with boiling water and a sharp razor, it’s as if he’s cutting his own throat. When I tell him to let his valet, Heinz, shave him, he screams: “Nobody comes near my throat. Nobody!” Heinz was required to shave a balloon over 100 times before ever touching the Führer. But I have access to that glorious neck. I secretly glow even in his enraged outbursts—me—Eva Braun from Simbach, Bavaria. I lie across his throat at night and do such unordinary wonderful things under his chin. I cheer him up by talking about the death of Roosevelt because it makes him remember that the death of Tsarina Elizabeth brought good luck to old Frederick. Adi attests that Franklin married his sister. Eleanor wasn’t really his cousin, and inbreeding caused his paralysis.

“FDR is bringing me the luck of Frederick,” he says.

It was some time before I knew that Franklin, FDR, and Roosevelt were one and the same person.

“Don’t you find it amusing that you and Roosevelt both came to power in the same year?”

“The year 1933 is essential to my destiny, not amusing. Roosevelt and I were meant to be opponents.”

“You and Roosevelt both come from difficult origins. You… from being poor. He… from being crippled.”

“Yes. There is that. Yet I was never really able to hate him for he was as mad as Wilson. But now at last crazy Franklin is gone.”

“Herr Roosevelt’s death hasn’t stopped the bombing above us,” I offer. Then I feel instantly sorry for having said it. But Adi is not angry. Pure honesty often makes him amorous.

“I can always count on you for the truth, little Evchen.” He pulls me to his chest. “We are soup souls.”

“You’re the only man I’ve ever loved.” I help him lift my skirt wishing he would forget the soup part and say we’re love souls.

6

ONE PERSON WHO REALLY UNDERSTOOD Adi’s magic was Göring, the Reich’s commissioner for aviation. “Hitler is explainable. It’s the explanations of him that are miraculous, my Eva.”

Göring could be sweet, like on one of Adi’s birthdays. As I planned a small party, I wanted to look special so Hermie told me to come to Karinhall, his country hunting lodge, and we’d paint our fingernails together. He picked Dreadful Sublime, his own name for the tango-ruby bottle of polish that he mixed and created himself. As Adi hates anything that’s not natural, I use clear gloss, though I do wear a little hint of lipstick.

Goebbels planned to place his usual annual speech in a gold frame for Adi, a speech that began with… “The Führer is within each of us and each of us is within him.” I hated that because I felt Adi was really only within me.

Göring grimaced. “Goebbels’ overworked huzza of a tribute.”

“Better than his awful slogan that… BUTTER MAKES YOU FAT, BULLETS MAKE YOU STRONG.”

“Ach! Guns before butter policy. Why not butter and guns.” Smearing his cheeks with liquid rouge, he almost looked like a chunky boy.

“Hermie Göring, why do you do this to yourself?” I couldn’t help laughing.

“I sing all the songs of my country, one song being pornography. I see no reason for having any kind of itch you cannot scratch.”

“Be serious, tell me, “I demanded.

“Somebody in the Reich has to be obvious. There’s little difference between flamboyance and adoration.” He began to rub his raw looking hands with thick lotion. His fingers are a strange purple-red, obviously the results of pills and shots that Dr. Morell gives him regularly. “Don’t you see, Evie, this throws them off. Have you heard people say that I drink schnapps through a straw at the Esplanade Hotel? And eat twenty lobsters at one time with the ladies from the Berlin Scala? My dear, I don’t drink anything as silly as schnapps, and I’m only capable of finishing off a dozen and a half lobsters in one sitting. Still, does such a febrile fancy make me an idiot?”

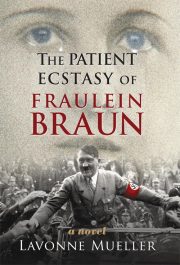

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.