Humming without fear, an old man and woman emerge from a bombed out building with seemingly no awareness of war.

To pass the time as we’re hunkered down, the major explains the different weapons calmly, almost poetically, as if he’s looking up to the heavens on a peaceful night and pointing out the stars. “That’s a mortar. They all have a slow strung-out sound. Hear? Like one stroke on the violin. Now those are plain old artillery shells, and they go a little faster, a kind of bass fiddle. Heavy artillery? That’s a speedy sound, trumpeting. And detonation is the bassoon, the most glorious loud bash of all.”

Adi would like the major’s symphonic sense of war, and I’m grateful to him for calming me down. Breathing more calmly, I smell gasoline, urine and feces as I listen to bombardments as an orchestra. Perhaps it’s Wagner at work, even Strauss though Adi came to hate him for statements Strauss made against the Reich.

Crawling carefully on his belt buckle, the major moves ahead to make sure we’re safe before coming back for me. Suddenly we hear the click of a safety catch. I freeze. Tense. Fear grips me as it always does with the horrible notion that I will die without Adi at my side. But the major pats my arm in assurance. “Russian rifles don’t have safeties. It’s German.”

And indeed a German soldier wearing a leather hat with thick loose earflaps rises not far from us, salutes, and runs into a building firmly clutching his rifle.

The noise ceases and the major leads me from debris. “If you have any influence with the Führer,” he says, “you should tell him to order officers who are at the front to be stationed at Headquarters. General Staff Officers who are sitting on their same swivel chairs from World War I should go immediately to the front. The Great War Headquarters can’t help us understand… this.” He points around. “Any change, even at this late day, could only help.”

“Major, the Führer will not permit any of his personal staff to be removed.”

“Such devotion is admirable but perhaps not useful.”

“His personal staff is not responsible for all this destruction.”

“Göring is! We are suffering because of the Luftwaffe’s failure to put a roof over our fortress.”

“Let us not forget, Major, that Ribbentrop by his arrogance and lack of moderation alienated the neutral powers.”

“Perhaps that is so.”

We don’t speak for a few minutes and then he wants to know if I still wish to push ahead to search for Renate. I do. We’ve come this far. He takes my hand with his, a surprisingly soft hand, a Golden Pheasant’s hand, the hand of a man who deals not only with weapons but also with confidential papers, circulars and special reports. He tells me he started out wanting to be just a “gray easel” (what the old-timers call the handbook for the general staff officers). Desk work is all right, but he needs action, too.

Am I a special paper? Squeezing my fingers together as we walk, he slowly separates each finger,, lingering in between. Is this a gesture of comfort or desire? How many times does the major have to relieve himself? Twice since I’ve been with him and probably this morning with his wife, too.

“Where is your wife, Major?”

“I put her on the train to Pomerania this morning.”

As we come to a populated area, I’m sure it’s Renate’s street. The ground is churned and mixed so that there’s no level place to walk. We see a woman in mourning though wearing black mourning is verboten. “You should be happy your son or husband died for the fatherland,” the major shouts.

An old man from the People’s Militia stops us, and the major flashes his identification card. Apologizing for any inconvenience, the Militia man goes to a woman holding a hand to her bloody head. I call after him, “Do you know a Renate Müller? She lives around here.”

He says the people living here are all dead except for the woman with a bloody head.

The wounded woman is astonished to learn she’s the only one left in her neighborhood.

The major is particularly glad that this woman and other civilians aren’t directing any hostility toward a soldier who is still fighting.

“My parents were crushed a week ago in the night. But bombs came over this morning,” the woman says, rubbing her head and looking up. “My daughters were able to die today in the light.”

“It was Ajax in the Iliad who wished to die in sunlight,” the major says, eager to display his learning. “You must know homer.”

“No,” she says with a hoarse voice. “He doesn’t live around here.”

“Do you know Renate Muller?” I ask.

“I know no Renate.” She feels the bleeding and rips her blouse sleeve off to wrap around her head.

“You can get out of here if you find your way to the Pichelsdorf bridge,” the People’s Militia man tells us.

“You should get out,” the major says. “The Russians will be here in full force very soon.”

“I went to school in Moscow. I can deal with them,” he replies.

As we walk, the major scans the streets and tells me Russia’s heavy tanks are better than the Germans thought. But the Red Army has little artillery, so why didn’t we take advantage of that? The German soldier got over his fear of facing Russian soldiers in combat long ago. Dread of being captured is the problem. The fear of Siberia hangs over every German’s head. Siberia is the Russian bomb. German soldiers fight harder because of Siberia, but it also wears away their confidence.

“We have good tanks, too.” I sift through bricks and broken concrete for any sign of Renate’s apartment.

“Not as good as the Russian T.34 tank. Russians hate frills like wireless controls, and they concentrate on bare necessities. They’ve shattered us, and now they’re shattering our remains.”

Babies cry with little paper bandages on their faces, and mothers hush them with soft songs. If I can only find Renate sitting on the stubble next to her cross-eyed child with my dress in her arms.

“The Red Army didn’t fully use air power,” the major says looking at the bombed earth. “If I were one of the commanders in the Red Army, you can make sure I’d use parachute troops because who would expect that? It was not prudent that we use them. The Führer told us that Crete proved the days of the parachute are over. It’s a surprise tactic and the surprise element was gone. But our generals didn’t listen and German paratroopers bled on the Eastern Front. The Führer is always right.”

23

A TORN SCARF LOOKS FAMILIAR, but it’s only cotton. Renate would never wear anything so coarse, and since her husband the butcher was with the occupying forces in Paris as a company cook, I’m sure she has a store of good silk.

“Are Russian generals as bad as ours?”

“Zhukov is competent. He got his training in Germany. The Russians consider him an outsider.”

Maybe there would be less rape of German women if Zhukov were around.

A young German soldier on the ground is wheezing from blood-choked lungs. A sucking chest wound, it’s a continual problem on the front as ordinary gauze sticks to the skin when applied to this kind of injury. Recently, German doctors made Vaseline gauze that works wonders. Unfortunately, the major no longer has a sterilized can of the Vaseline gauze with him. The last container was used weeks ago. He pats the private on the forehead as glistening fresh blood sticks to his sleeve.

A strong sound of engines up above startles me. I crouch down.

“Sewing machines,” the major says. “That’s what we call Russian biplanes on harassing missions trying to buzz us to death.”

Crushed between mounds of mud is an old bell tower. The major is happy to see there’s no bell inside. We need iron, and all church bells in Germany are confiscated for the war effort. Is this just another clever way for Adi to strike back at the Church?

“Those dead German soldiers you see hanging,” the major says pointing, “are traitors we strung up on tram pylons. Executed as deserters.”

As the last two weeks were warm and dry, the firestorm raids have done more damage. Strong drafts create swirls of heat with smoke three or four miles high. Firemen can’t stop the flames, so they concentrate on freeing people trapped under debris. Searing heat shrinks and shrivels the dead and dying.

“Look at this!” The major points to the scorched remains of a soldier. The lower part of the body is naked, and his sex organ is mummified and grossly extended.

“General Keitel collects these things.” Taking out his handkerchief, he tugs the expanded penis away from the blasted groin. It breaks free as delicately as a lace border pulled from a tablecloth.

“What if it’s one of our soldiers?” I can’t look at this elongated distortion that the major carries on his handkerchief, one end sticking straight out like some awful beastly stump.

“All the better, don’t you think? We’re merely preserving German manhood.”

“What does Herr General do with these things?” Not even latrine gossip has learned of Keitel’s collection.

“He has a personal museum.“

Petrified body parts make me realize there’s no reason now to hunt anymore for Renate. If she was smart, she left weeks ago with her family. If she remained, then she’s dead in her tunnel apartment still holding fast to her kitchen table and her hand-painted dishes, maybe mummified herself. I’ll never get my dress back or be able to tell her that she was wrong. All those days she followed me around Munich laughing as I placed a passionate kiss in the armpit of every statue of the Führer. Well, Renate, I’m marrying Him!

Wrapping it carefully with the pages of a lengthy confidential report, the major puts the calcified organ carefully under his seat. This penis will get him whiskey from the general, maybe even a two-day pass.

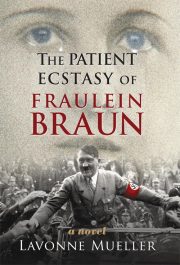

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.