“An SS doctor tells me that mummified parts are worse than cutting through stone.”

I don’t want to see such things, but that would be womanly, and he’d start patronizing me again.

Before we begin driving off, I write a note to Renate on a block of concrete that was blasted away from a storefront. I grab a piece of stone with a sharp edge and write, “Renate, I A M T F.”

“What is I A M T F?” Perplexed, his high forehead forms one large crease from side to side.

“I am marrying the Führer.” I proudly emphasize each word.

“Why didn’t you just write that?”

“You of all people ask me that?”

“Jews might read it? Surely there are no Jews left in Berlin.”

Jews like my mother’s cook, Thilde, never bother with gossip though Adi says poor Thilde and her kind could never understand Die Meistersinger. I mean officers’ wives. They’re the worse gossips, eager to look down on me because I don’t have a “von” before my name.

Tugging the strap of a box, an old woman stumbles and falls to the ground. A dead charred baby falls out. Stuffing it back in, she runs through a smoky path when her head is blown off—still holding the box, she continues a few more steps before falling.

Her flowery dress half eaten by fire, a young girl asks us where a first aid station is. Seeping sores line her legs. We can’t tell her where there’s a hospital that hasn’t been bombed, but we take her to a nearby shelter clinic. “I’m so hungry,” she moans, “I use vomit from the dying to trap rabbits and cats.”

A warped C ration can left by a soldier is in the street, and I tell her to take it.

“How can I? It’s American. The Germans will think I’m a spy.”

“Soon you and your friends can eat all the American food you want,” the major says. “Americans will be here shortly.”

On the street ahead, hot asphalt has melted an old man into its porous clutches—up to the neck.

“I should shoot the poor man and put him out of his misery.” The major touches the Luger at his side. “I can’t afford to waste ammunition.”

Untouched by smoke and black soot, a woman wearing a large hat with red poppies approaches the asphalt-planted man and places a gray fedora on his head to shield him from blowing plaster and gravel. Sitting on the ground next to him, she takes out bottles of water and little wedges of cheese.

“The good German Hausfrau to the end.” The major finds the true spirit of his homeland in the smallest detail. If only his brandy flask were not empty, for the asphalt-husband and his wife deserve a drink.

Moving toward us are wounded people crawling at our feet, begging for help—a young girl with torn arms, an old man with blood on his chest, crying children. Will they ever eat strudel again? Feel the weight of a parade flag on their shoulders? Brush their teeth again? I’m privileged by just breathing.

We jump in the vehicle ready to return to the Bunker through the ravaged roads. But a boulder in the street blocks our way after only a few minutes, as streetcar tracks were blown from their beds. The major tries to shove smoldering wood out of our path. To the side of the road, we hear a howl, a creature’s sound but perhaps human, too. Clearing away rubbish, the major lifts out a scrappy dog.

“See what I saved.” Holding up the mongrel proudly, he slaps dust from its brown fur. “Skinny but still alive. The Führer will reward me handsomely for saving a dog.” Giving the cur water from his canteen, he then walks ahead to a girl who is swaying aimlessly around a swirl of fire clutching a half loaf of bread. Stopping her with one broad thrust of his hand, he breaks the bread in half giving the girl a chunk and keeping the bigger part for himself. We get back in the jeep.

He feeds the dog bread as we drive, and it eats hungrily, scattering chunky crumbs up into the air and on my dress like the flecks of plaster and concrete falling outside.

“A survivor, this little bitch.” The major boldly swings around wagons, burning porch posts, and furniture wormed with bullet holes. “What shall we call her?”

“Renate.”

“We’ve found Renate, after all.” Laughing, he slaps me on one thigh. It’s a friendly slap, but what would it be like if he didn’t take his hand away? I blush and feel guilty. In just a few hours, I’ll be a married woman.

Renate puts her nose into the deepest corner of my lap. A stirring moves up to my stomach, and I’m embarrassed. A dog can do that to me? I push her snout away, and she stretches out to sleep, her head on the major’s lap, her hindquarters on mine.

Driving carefully and avoiding every pitfall, the major is silent. Destruction passes by as if it were a movie, as if this were some Goebbels’ newsreel showing the bombardment we’ve unleashed on enemy cities. It’s like the American novel I read about the destruction of the South during the civil war. Scarlett O’Hara. Am I like that? A woman who has to endure war but has a great love?

“Major, have you read Gone with the Wind?”

“You ask that when Clark Gable flies a bomber over Germany? ”

“Gable isn’t in the book. 300,000 copies were sold in Germany. Aren’t you even curious?”

“One is always curious, Fräulein. I own an American stove!”

As we drive over two heavy beer signs, Renate’s leg digs into my groin jolting that locus already so warm and vulnerable. We three bounce up in the air—me with a short climax of quick release—before falling back to our seats.

“Sorry,” the major says. “I’ve no control over all the devastation cluttering the streets, though our long wide boulevards are good fire breaks. We haven’t endured a firestorm. Not like Hamburg or Dresden.”

“But we have the same ruin.”

“Our ruins are excellent enemy barriers.”

“And you’re a good driver.” I remove Renate’s leg from my lap and place it carefully on my knee.

We’re flagged down by a man dressed as a clown. His costume is clean and sparkling. In all the grime, how is he able to stay unsoiled?

“Stoi!” the major orders. “We’re on duty for the Führer.”

“Sir.” The clown salutes. “We’re official as well. The Berlin Relief Ensemble validated by the Reich,” he says in a broad Baden dialect.

“Major, I believe he’s authentic. Goebbels convinced the Führer that Berlin is still our theatrical center.”

“Nevertheless, I’d prefer him to remain at hand-grenade distance.” Holding Renate tightly for fear his reward might get away from him, we climb out of the Kubelwägen.

“Why aren’t you in uniform? Defending Berlin?”

“Sir.” The clown’s voice is deep. “We’re here to uplift the German spirit.”

“Where are your fellow uplifters, Prince of Clowns?”

“Call me Dunce, Major. In the theatre world, titles don’t matter.”

“Mein Dunce, then.”

“Please follow me.” The clown steers us to a small tunnel that’s reinforced with bricks and concrete. It’s the worse section of the city—Mulackstrasse—the alleyways of prostitutes and criminals. Coming out of a tunnel, we enter a basement with seats and stage and sit in the front row, Renate secure on the major’s lap. Behind us is an audience of people with faces blackened from bombardment, some with arms and legs smeared in red brittle powder. A war audience. Nobody speaks. It’s weirdly quiet. A smudged mask of charred amber looks at me with eyes that show no reaction to my stare.

Taking off his billowing pants, the clown stands before us in black glass shorts and a polka-dotted shirt. He announces, “There is a tide in the affairs of men, which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune.”

“Shakespeare,” the major says.

“Julius Caesar,” the clown adds.

“Act IV, Scene 3.” The Major smiles proudly. “Our family tutor was an Englishman.”

The clown calls to a young woman in yellow leggings who comes on stage. Her hair is the same yellow as her tights. With no crotch in her tights, her light brown pubic hair bushes at the opening.

With gaudy fingers painted in stripes of yellow and green, the clown taps his glass underwear.

“Isn’t love a delicate matter?” the clown shouts.

The girl in yellow tights shouts as she runs offstage, “Where is the 1,000 pound Reich person?”

“Leading the dying Luftwaffe Air Force on his motorcycle.” The clown waves his hands like fluttering wings.

Doubling over in laughter, the major stamps his feet in approval. He hates Göring.

“Göring can sometimes be charming,” I whisper to the major.

“Charming loses wars.”

“And he lost a nephew. Peter Göring died in a dogfight over the Channel.”

“Peter Göring was a talented fighter pilot and liked in spite of having a dummi-dummi uncle. Now Peter is in Soldiers’ Cemetery at Abbeville where his other comrades of the Schlageter Squadron rest.” The major motions for the clown to continue.

The clown announces, “All women in the audience are to sit on the laps of men.”

Looking at me with a persuading smile, the major pushes his legs close together.

What can I do? I gently lower myself on his lap, and a thick warm bulge presses into me.

There’s no movement from the crowd behind me. Silence. Are they all women?

“Women, then, on women’s laps,” the clown orders. A rustling noise as the dusty mannequins sit upon each other. “When just a little boy, the Führer came to my school,” the clown says. “I told him I wanted to be a great soldier. What should I do? The Führer told me to unclog the kitchen zinc.”

The major and I laugh. That’s Adi, the practical man, the corporal.

The audience remains lifeless, only their eyelids moving in creases of soot.

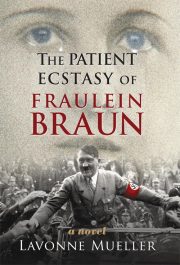

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.