I can’t disagree. The Spanish treasure ship was blown into Plymouth expecting sanctuary, and Cecil, the son of a poor man, could not resist the gold it carried. He stole the gold—simple as that. And now the Spanish are threatening a blockade of trade, even war, if we do not pay it back. We are utterly in the wrong, all because Cecil is utterly in the wrong, but he has the ear of the Queen of England.

Howard masters his irritation with some difficulty. “Please God we never see the day when you come to me and say I was right to fear him and we should have defended ourselves, but now it is too late and one of our own is on trial for some trumped-up charge. Please God he does not pick us off one by one and we too trusting to defend ourselves.” He pauses. “His is a rule of terror. He makes us afraid of imaginary enemies so we don’t guard ourselves against him and against our government. We are so busy watching for foreigners that we forget to watch our friends. Anyway, you keep your counsel and I’ll keep mine. I’ll say no more against Cecil for now. You will keep this close? Not a word?”

The look he gives me persuades me, more than any argument. If the only duke in England, cousin to the queen herself, should fear his own words’ being reported to a man who should be little more than a royal servant, it proves that the servant has become overmighty. We are all growing afraid of Cecil’s knowledge, of Cecil’s network of intelligencers, of Cecil’s growing silent power.

“This is between the two of us,” I say quietly. I glance around to see that no one is in earshot. It is amazing to me that I, England’s greatest earl, and Howard, England’s only duke, should fear eavesdroppers. But so it is. This is what England has become in this tenth year of Elizabeth’s reign: a place where a man is afraid of his own shadow. And in these last ten years, my England seems to have filled with shadows.

1568, WINTER,

BOLTON CASTLE:

MARY

Irefuse, I utterly refuse to wear anything but my own gowns. My beautiful gowns, my furs, my fine lace collars, my velvets, my petticoats of cloth of gold were all left behind in Holyroodhouse, dusted with scented powder and hung in muslin bags in the wardrobe rooms. I wore armor when I rode out with Bothwell to teach my rebel lords a lesson, but it turned out I was neither teacher nor queen, for they beat me, arrested me, and hunted Bothwell down for an outlaw. They imprisoned me and I would have died in Lochleven Castle if I had not escaped by my own wits. Now, in England, they think I am brought so low as to wear hand-me-downs. They think I am sufficiently humbled to be glad of Elizabeth’s cast-off gowns.

They must be mad if they think that they can treat me as an ordinary woman. I am no ordinary woman. I am half divine. I have a place of my own, a unique place, between the angels and nobles. In heaven are God, Our Lady, and Her Son, and below them, like courtiers, the angels in their various degrees. On earth, as in heaven, there are the king, the queen, and princes; below them are nobles, gentry, working people, and paupers. At the very lowest, just above the beasts, are poor women: women without homes, husbands, or fortune.

And I? I am two things at once: the second-highest being in the world, a queen, and the very lowest: a woman without home, husband, or fortune. I am a queen three times over because I was born Queen of Scotland, daughter to King James V of Scotland, I was married to the Dauphin of France and inherited the French crown with him, and I am, in my own right, the only true and legitimate heir to the throne of England, being the great-grandniece to King Henry VIII of England, though his bastard daughter, Elizabeth, has usurped my place.

But,voilа! At the same time I am the lowest of all things, a poor woman without a husband to give her a name or protection, because my husband the King of France lived for no more than a year after our coronation, my kingdom of Scotland has mounted an evil rebellion against me and forced me out, and my claim to the throne of England is denied by the shameless red-haired bastard Elizabeth who sits in my place. I, who should be the greatest woman in Europe, am reduced so low that it is only her support that saved my life when the Scots rebels held me and threatened my execution, and it is her charity that houses me in England now.

I am only twenty-six years old and I have lived three lifetimes already! I deserve the highest place in the world and yet I occupy the lowest. But still I am a queen, I am a queen three times over. I was born Queen of Scotland, I was crowned Queen of France, and I am heir to the crown of England. Is it likely I will wear anything but ermine?

I tell my ladies-in-waiting, Mary Seton and Agnes Livingstone, that they can tell my hosts, Lord and Lady Scrope of Bolton Castle, that all my gowns, my favorite goods, and my personal furniture must be brought from Scotland at once and that I will wear nothing but my own beautiful clothes. I tell them that I will go in rags rather than wear anything but a queen’s wardrobe. I will crouch on the floorboards if I cannot sit on a throne under a cloth of estate.

It is a small victory for me as they hurry to obey me, and the great wagons come down the road from Edinburgh bringing my gowns, my bureaux, my linen, my silver, and my furniture, but I fear I have lost my jewels. The best of them, including my precious black pearls, have gone missing from my jewel chests. They are the finest pearls in Europe, a triple rope of matched rare black pearls; everyone knows they are mine. Who could be so wicked as to profit from my loss? Who would have the effrontery to wear a queen’s pearls robbed from her ransacked treasury? Who would sink so low as to want them, knowing they had been stolen from me when I was fighting for my life?

My half brother must have broken into my treasure room and stolen them. My false brother, who swore to be faithful, has betrayed me; my husband Bothwell, who swore he would win, is defeated. My son James, my most precious son, my baby, my only heir, whom I swore to protect, is in the hands of my enemies. We are all forsworn, we are all betrayers, we are all betrayed. And I—in one brilliant leap for freedom—am somehow caught again.

I had thought that my cousin Elizabeth would understand at once that if my people rise against me in Scotland, then she is in danger in England. What difference?Rien du tout! In both countries we rule a troublesome people divided in the matter of religion, speaking the same language, longing for the certainties of a king but unable to find anyone but a queen to take the throne. I thought she would grasp that we queens have to stick together, that if the people pull me down and call me a whore, then what is to stop their abusing her? But she is slow, oh God! She is so slow! She is as sluggish as a stupid man, and I cannot abide slowness and stupidity. While I demand safe conduct to France—for my French family will restore me to my throne in Scotland at once—she havers and dithers and calls for an inquiry and sends for lawyers and advisors and judges and they all convene in Westminster Palace.

To judge what, for God’s sake? To inquire into what? For what is there to know?Exactement! Nothing! They say that when my husband, the fool Darnley, killed David Rizzio, I swore vengeance and persuaded my next lover the Earl of Bothwell to blow him out of his bed with gunpowder and then to strangle him as he ran naked through the garden.

Madness! As if I should ever allow an assault on one of royal blood, even for my own vengeance. My husband must be as inviolable as myself. A royal person is sacred as a god. As if anyone with half a wit would commission such a ridiculous plot. Only an idiot would blow up a whole house to kill a man when he could easily smother him with a quiet pillow in his sottish sleep! As if Bothwell, the cleverest and wickedest man in Scotland, would use half a dozen men and barrels of gunpowder, when a dark night and a sharp knife would do the deed.

Finally, and worst of all, they say that I rewarded this incompetent assassination by running off with the assassin, the Earl of Bothwell, conceiving children in adulterous lust, marrying him for love, and declaring war against my own people for sheer wickedness.

I am innocent of this, and of the murder. That is the simple truth and those who cannot believe it have made up their minds to hate me already for my wealth, for my beauty, for my religion, or because I was born to greatness. The accusations are nothing but vile slander,calomnie vile . But it is sheer folly to repeat it word for word, as Elizabeth’s inquiry intends to do. Utter idiocy to give it the credence of an official inquiry. If you dare to say that Elizabeth is unchaste with Robert Dudley or any other of the half-dozen men who have been named with her through her scandalous years, starting with her own stepfather Thomas Seymour when she was a girl, then you are dragged before a justice of the peace and your tongue is slit by the blacksmith. And this is right and proper. A queen’s reputation must be untouched by comment. A queen must seem to be perfect.

But if you say thatI am unchaste—a fellow queen, anointed just as she is, and with royal blood on both sides that she lacks—then you can repeat this in Westminster Palace before whoever cares to come by to listen, and call it evidence.

Why would she be such a fool as to encourage gossip about a queen? Can she not see that when she allows them to slander me she damages not just me but my estate, which is exactly the same as her own? Disrespect to me will wipe the shine off her. We should both defend our state.

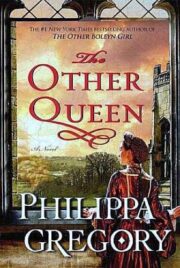

"The other queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The other queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The other queen" друзьям в соцсетях.