She understands me well enough to give me a quick sideways smile. “She is,” she says. She means that the famous Tudor temper is not unleashed. I have to admit I am relieved. The moment that she sent for me I was afraid I would be scolded for letting the inquiry reach no damning conclusion. But what could I do? The terrible murder of Darnley and her suspicious marriage to Bothwell, his probable killer, which appeared as such a vile crime, may not have been her fault at all. She may have been victim rather than criminal. But unless Bothwell confesses everything from his cell, or unless she testifies to his wickedness, no one can know what took place between the two of them. Her ambassador will not even discuss it. Sometimes I feel that I am too frightened even to speculate. I am not a man for great sins of the flesh, for great drama. I love Bess with a quiet affection; there is nothing dark and doomed about either of us. I don’t know what the queen and Bothwell were to each other, and I would rather not imagine.

Queen Elizabeth is seated in her chair by the fireside in her private chamber, under the golden cloth of estate, and I go towards her and sweep off my hat and bow low.

“Ah, George Talbot, my dear old man,” she says warmly, calling me by the nickname she has for me, and I know by this that she is in a sunny mood, and she gives me her hand to kiss.

She is still a beautiful woman. Whether in a temper, whether scowling in a mood or white-faced in fear, she is still a beautiful woman, though thirty-five years of age. When she first came to the throne she was a young woman in her twenties and then she was a beauty, pale-skinned and red-haired with the color flushing in her cheeks and lips at the sight of Robert Dudley, at the sight of gifts, at the sight of the crowd outside her window. Now her color is steady, she has seen everything there is to see, nothing delights her very much anymore. She paints on her blushes in the morning and refreshes them at night. Her russet hair has faded with age. Her dark eyes, which have seen so much and learned to trust so little, have become hard. She is a woman who has known some passion but no kindness, and it shows in her face.

The queen waves her hand and her women rise obediently and scatter out of earshot. “I have a task for you and for Bess, if you will serve me,” she says.

“Anything, Your Grace.” My mind races. Can she want to come to stay with us this summer? Bess has been working on Chatsworth House ever since her former husband bought it, for this very purpose—to house the queen on her travels to the North. What an honor it will be, if she plans to come. What a triumph for me, and for Bess’s long-laid plan.

“They tell me that your inquiry against the Scots queen, my cousin, failed to find anything to her discredit. I followed Cecil’s advice in pursuing the evidence till half my court was turning over the midden for letters and hanging on the words of maids spying at bedroom doors. But there was nothing, I believe?” She pauses for my confirmation.

“Nothing but gossip, and some evidence that the Scots lords would not publicly show,” I say tactfully. “I refused to see any secret slanders as evidence.”

She nods. “You would not, eh? Why not? Do you think I want a dainty man in my service? Are you too nice to serve your queen? Do you think this is a pretty world we live in and you can tiptoe through dry-shod?”

I swallow on a dry mouth. Pray God she is in a mood for justice and not for conspiracy. Sometimes her fears drive her to the wildest of beliefs. “Your Grace, they would not submit the letters as evidence for full scrutiny; they would not show them to the Queen Mary’s advisors. I would not see them secretly. It did not seem to be…just.”

Her dark eyes are piercing. “There are those who say she does not deserve justice.”

“But I was appointed judge, by you.” It is a feeble response, but what else can I say? “I have to be just if I am representing you, Your Majesty. If I am representing the queen’s justice, I cannot listen to gossip.”

Her face is as hard as a mask and then her smile breaks through. “You are an honorable man indeed,” she says. “And I would be glad to see her name cleared of any shadow of suspicion. She is my cousin; she is a fellow queen; she should be my friend, not my prisoner.”

I nod. Elizabeth is a woman whose own innocent mother was beheaded for wantonness. Surely, she must naturally side with a woman unjustly accused? “Your Grace, we should have cleared her name on the evidence that was submitted. But you stopped the inquiry before it reached its conclusions. Her name should be free of any slur. We should publish our opinions and say that she is innocent of any charge. She can be your friend now. She can be released.”

“We will make no announcement of her innocence,” she rules. “Where would be the advantage to me in that? But she should be returned to her country and her throne.”

I bow. “Well, so I think, Your Grace. Your cousin Howard says she will need a good advisor and a small army at first to secure her safety.”

“Oh, really? Does he? What good advisor?” she asks sharply. “Who do you and my good cousin nominate to rule Scotland for Mary Stuart?”

I stumble. It is always like this with the queen: you never know when you have walked into a trap. “Whoever you think best, Your Grace. Sir Francis Knollys? Sir Nicholas Throckmorton? Hastings? Any reliable nobleman?”

“But I am advised that the lords of Scotland and the regent make better rulers and better neighbors than she did,” she says restlessly. “I am advised that she is certain to marry again, and what if she chooses a Frenchman or a Spaniard and makes him King of Scotland? What if she puts our worst enemies on our very borders? God knows her choice of husbands is always disastrous.”

It is not hard for a man who has been around the court for as long as I have to recognize the suspicious tone of William Cecil through every word of this. He has filled the queen’s head with such a terror of France and Spain that from the moment she came to the throne she has done nothing but fear plots and prepare for war. By doing so, he has made us enemies where we could have had allies. Philip of Spain has many true friends in England and his country is our greatest partner for trade, while France is our nearest neighbor. To hear Cecil’s advice you would think one was Sodom and the other Gomorrah. However, I am a courtier, I say nothing as yet. I stay silent till I know where this woman’s indecisive mind will flutter to rest.

“What if she gains her throne and marries an enemy? Shall we ever have peace on the northern borders, d’you think, Talbot? Would you trust such a woman as her?”

“You need have no fear,” I say. “No Scots army would ever get past your Northern lords. You can trust your old lords, the men who have been there forever. Percy, Neville, Dacre, Westmorland, Northumberland, all of us old lords. We keep your border safe, Your Grace. You can trust us. We keep armed and we keep the men levied and drilled. We have kept the Northern lands safe for hundreds of years. The Scots have never defeated us.”

She smiles at my assurance. “I know it. You and yours have been good friends to me and mine. But do you think I can trust the Queen of Scots to rule Scotland to our advantage?”

“Surely, when she goes back she will have enough to do to reestablish her rule? We need not fear her enmity. She will want our friendship. She cannot be restored without it. If you help her back on her throne with your army, she will be eternally grateful. You can bind her with an agreement.”

“I think so,” she nods. “I think so indeed. And anyway, we cannot keep her here in England; there is no possible argument for keeping her here. We cannot imprison an innocent fellow queen. And better for us if she goes back to Edinburgh than runs off to Paris to cause more trouble.”

“She is queen,” I say simply. “It cannot be denied. Queen born and ordained. It must be God’s will that she sits on her throne. And surely, it is safer for us if she can bring the Scots to peace than if they are fighting against each other. The border raids in the North have been worse since she was thrown down. The border raiders fear no one, now that Bothwell is far away in prison. Any rule is better than none. Better the queen should rule than no rule at all. And surely, the French or the Spanish will restore her if we do not? And if they put her back on the throne we will have a foreign army on our doorstep, and she will be grateful to them, and that must be far worse for us.”

“Aye,” she says firmly, as if she has made a decision. “So think I.”

“Perhaps you can swear an alliance with her,” I suggest. “Better to deal with a queen, you two queens together, than be forced to haggle with a usurper, a new false power in Scotland. And her half brother is clearly guilty of murder and worse.”

I could not have said anything that pleased her more. She nods and puts her hand up to caress her pearls. She has a magnificent triple rope of black pearls, thick as a ruff, around her throat.

“He laid hands on her,” I prompt her. “She is an ordained queen and he seized her against her will and imprisoned her. That’s a sin against the law and against heaven. You cannot want to deal with such an impious man as that. How should he prosper if he can attack his own queen?”

“I will not deal with traitors,” she declares. Elizabeth has a horror of anyone who would challenge a monarch. Her own hold on her own throne was unsteady in the early years, and even now her claim is actually not as good as that of the Queen of Scots. Elizabeth was registered as Henry’s bastard and she never revoked the act of parliament. But Mary Queen of Scots is the granddaughter of Henry’s sister. Her line is true, legitimate, and strong.

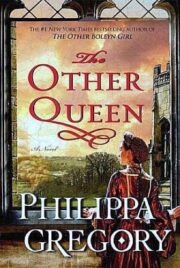

"The other queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The other queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The other queen" друзьям в соцсетях.