André’s features looked as though they had been etched in acid. “If not I, who else? I promised to get him out. I failed.”

“You did get him out,” Laura pointed out. “Otherwise, he wouldn’t be here. Quod erat demonstrandum.”

André didn’t smile at the reference to Candide. “I may have removed him from the Temple, but not until he was rendered incapable of performing the one function that makes his life worth living. Trust me, he was very blunt about that.” André’s expression was bleak. “He told me to leave him.”

“He didn’t mean it.”

“You didn’t hear him.”

Laura remembered that last night at the Hôtel de Bac, the anxious consultations, the preparations for the children, André’s face gray with fatigue. “Did he realize what you were risking in going back for him? But for him, you might have stayed as you were. No one would have been any the wiser. I certainly wasn’t.”

Although she should have been. The clues had been there, if she had cared to piece them together.

André looked ruefully down at her. “Did you ever think of taking up work as an advocate? You would have been quite good at it.”

Laura accepted the tacit change of topic. “Far better than I am as an actress.”

André braced a hand on the wall behind her. “You had me quite convinced with your performance as Suzette. For a moment, I wondered if—”

“If?” There was no reason for Laura’s blouse to feel so tight.

André shook his head, looking bemused. “If you were what you said you were. You play the seductress extremely well.”

His eyes were the color of the remembered waters of her childhood, the shores of Italy on a sunny day. Laura couldn’t seem to look away.

“It was all an act,” she said, her voice unsteady. “Just an act.”

André’s hand was still braced on the wall above her head, but the space between them seemed to have contracted. “I thought you said you couldn’t act.”

Laura tilted her head up at him. An unnecessary gesture. They were nearly of a height to begin with. “I’m better offstage than on.”

“Are you?” he said huskily, his lips so close that she felt the words as much as heard them, in the brush of his breath and the rise and fall of his chest.

If she closed her eyes, she didn’t have to think about what she was doing or not doing. If she closed her eyes, she didn’t have to see his hand rise to smooth the hair away from the side of her face, or his head tilt to match his lips to hers. If she closed her eyes, it was none of it real, the movement of his lips against hers, his hand cupping her cheek, his tongue tracing the contours of her mouth. If it wasn’t real, she didn’t have to make him stop.

Heaven only knew, she didn’t want it to stop. The paste pot clattered to the ground. As of their own volition, her arms twisted around his neck, drawing him closer, and the kiss changed. She could feel his response in the way his arms tightened around her—not the comfort of a comrade but the passion of a lover, pulling her closer, matching her body to his, his tongue slipping between her lips, kissing openmouthed, exchanging breath for breath, both clinging, fevered, wanting.

It was as it had been at the inn, but better. At the inn, they had been performing to an audience, but now . . .

Now.

Reality slammed in on Laura and she yanked back, her back hitting the wall, hard enough to make her see stars.

“What—,” she said hoarsely. What were they doing?

André Jaouen seemed as kerflummoxed as she was. He was breathing hard, his chest rising and falling erratically beneath his coat.

“Laura, I—”

Laura sidled sideways, away from André. Her ears were ringing as if someone had been singing a very high note very loudly just next to her.

She groped after logic. “We have to get back to the inn. We’ll be missed.”

André followed after her. “None of them are there. They’re all putting up playbills. Laura—”

She didn’t want to hear what he had to say. “What if they’ve returned already?” She was already backing out of the alleyway. “I wouldn’t want to add tardiness to my other shortcomings.”

André stopped short in the middle of the alley. He looked at her quizzically. “Are you running away?”

Who was he to talk about running away? And what was he thinking, going about kissing her like that? Did he think she wouldn’t care?

“I’m not your wife,” Laura announced. Her voice was pitched too high. It made her wince to hear it. That wasn’t her talking. It was someone else, someone briefly inhabiting her body, someone who had been kissing André Jaouen as though she meant it.

Her breasts still ached with it. What was her body thinking? That was the bother. It didn’t think, it felt. It was her job to do the thinking, no matter what her body wanted or thought she wanted.

“What are you saying?”

Laura held up the paste pot to ward André off. “No matter what we’ve been pretending”—her voice sounded unnaturally loud in the small alleyway—“I am not really your wife.”

“I was aware of that,” he said.

He seemed to be missing the point. “This past week—sharing as we have—” Laura’s voice had gone raspy. She coughed to clear her throat. The paste pot hung heavy from her hand. “Perhaps this wasn’t the best idea after all. I hadn’t thought . . .”

“Hadn’t thought what?” he pressed.

There was still a lump at the back of her throat, as though a whole pool of toads had bred and spawned in there. Her lips felt sore and swollen from his kiss, both her brain and lips slower and clumsier than usual.

“I hadn’t thought that I would grow so accustomed to you. That’s all. Here. You can put up the rest of the playbills.”

Pushing the paste pot at him, she set off at a pace that was practically a jog. He didn’t try to follow. Or, if he did, she didn’t see it.

Only Pantaloon and Leandro were in the common room of the inn, sharing a carafe of the house wine, when Laura came in.

“The children are already in bed,” Pantaloon informed her kindly. “Jeannette put them up an hour ago. You might want to do the same. A good night’s sleep, always a good thing before a performance. That’s what I told the others as well.”

“Mmmph,” said Leandro, into his wine.

“Well, good night, then,” said Laura vaguely as she took up a candle from the table and scurried up the stairs.

It was a good-size inn for a good-size town, although all but empty in the off-season. The troupe had almost entirely taken it over. There were eight doors on the hall, three opening off on either side. The inhabitants of the first room on the left had made the mistake of leaving the door slightly ajar.

Through it, Laura could hear the crinkle of a straw mattress and a voice whispering breathily. “I shouldn’t . . .”

“But you want to,” said de Berry confidently.

There was the rustle of clothing being either removed or displaced.

Rose let out a squeal. “Throw myself away on a penniless actor?” she demanded coquettishly.

More rustling. “You’d be surprised at what I have to offer.”

“But I imagine”—rustle, rustle—“you’re going to offer to show me.”

Oh, for heaven’s sake. Laura knew it was nearly spring, but did that mean everyone had to mate?

She made to hurry past, but was slowed as she spotted Harlequin, standing in the open door of the opposite room.

Catching her eye, Harlequin made a wry face. “Leandro will be sobbing over his wine again tonight.”

That was a safe enough prediction. “He already is. I don’t see what he sees in her,” Laura added waspishly.

“Don’t you?” Something in the way Harlequin said it made Laura wonder if it was entirely on Leandro’s account that Harlequin was concerned.

“I don’t,” said Laura firmly. “He’s worth ten of her, and you can tell him I said so. Besides, Gabrielle will be devastated if he doesn’t wait for her.”

Gabrielle would be nothing of the kind. For all that Leandro was a decade her senior, she treated him with the sort of patient condescension usually reserved by empresses for their underlings. But it seemed the right sort of thing to say.

Harlequin smiled faintly. “I’ll let him know.”

Laura continued on down the hall, to the room she was to share with André. Would he come to bed at all? Or would he emulate Leandro and spend his night on a settle by the hearth, regretting the impulse that had led him to offer consolation in the form of a kiss? Laura tried to imagine the paths of thought that might have led to it. The governess is whining, must shut her up. Oh, well, best stop her mouth. Or perhaps it had been some lingering memory of Suzette, the girl men couldn’t forget, before he remembered that in real life the beguiling Suzette was nothing more than plain Laura Griscogne, who balked desire simply by being herself.

That hadn’t been the case once upon a time.

She might not have been the prettiest girl in the group—and even then she had shown a dampening inclination to actually think things through, an attribute not considered an asset among her parents’ set—but she had been young and nubile and curious. Antonio had been a sculptor, come to study with her father. They had conducted several intriguing anatomy lessons down by the pier, with the stars glittering on the water. Laura had never been quite sure whether her parents knew or not.

There had never been any talk of love, although, like any fifteen-year-old, she had imagined herself in love, just a little bit.

But then the commission had come from England, and they had left Lake Como for Cornwall, where the stars were dimmer and the waters colder and the sea leapt up and swallowed up all there was of youth and joy and desire.

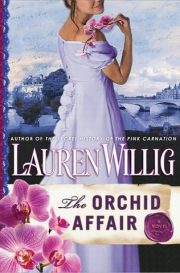

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.