“For warmth,” she agreed, and closed her eyes.

Despite André’s confident words, the next rehearsal wasn’t any better, nor the one after that. By the time they arrived in Beauvais, Laura’s nerves were as frazzled as her hair.

Despite everyone’s efforts to coach her, she only seemed to get worse rather than better—more clumsy, more tongue-tied, more prone to tripping over props. Here they were in Beauvais, with only one night left before they performed for an actual audience. They were renting the town hall, three nights of use in exchange for ten percent of their take, whatever that take might be. If they had a take.

Laura just hoped the audience didn’t ask for their money back.

Gabrielle was to be ticket collector; Pierre-André had been given the role of assistant prop-master (which, when translated, meant that he played backstage with the paper daggers until someone actually needed them). Jeannette had turned a pile of secondhand clothes into the last word in gaudy finery, embellished with enough frills, furbelows, and gold trim to keep even Rose happy. Everyone served a useful role.

Except Laura.

With one day to go until the performance, the troupe had dispersed to paper the town with playbills. At least, that was what they claimed to be doing. Based on the glint in de Berry’s eye as he set off with Rose, Laura had her doubts.

“I had acting lessons when I was young,” she fumed to André, slapping some paste on the back of a poster and slamming it with unnecessary force against the wall. “I was tutored by some of the best actresses at the Comédie-Française.”

“What sort of lessons?” André asked practically, reaching over her to tug down a crooked corner. “Memorizing speeches from Corneille and Racine?”

“Yes.” She had been rather good at those, actually. It had been easy enough to mimic the inflection of her teachers.

But that had been all it was, mimicry. She couldn’t create Medea’s madness on her own or Antigone’s pain. Left to herself, she had all the creativity that God gave a duck.

“Well, that explains it,” said André, in the sort of sensible tone designed to make someone want to claw his eyes out. And by someone, Laura meant her. “Those were set pieces. Memorization. It’s an entirely different art form.”

“Thank you so very much,” said Laura acidly. “I would never have realized that.”

For a man who had been married before, André was slow to pick up on the danger signs. “Classical theatre is a highly ritualized form, while the Commedia dell’Arte is all about spontaneity and improvisation.”

“You make me sound like an automaton.” Laura knew there was no reason to take it so to heart, but she was tired and frazzled and her emotions felt dangerously raw. The self-control she had so assiduously cultivated over the past sixteen years was cracking around the edges, like a piece of pottery left too long in the kiln. “Wind her up and watch her go! But don’t expect any original thought or any human feelings. She’s not capable of those.”

André looked at her in surprise. “I never said that.”

“No, but it’s true, isn’t it?” Laura suddenly felt dangerously close to tears. She pressed down hard on a wrinkle in the poster. “Never mind. I’m just tired, that’s all.”

André’s hands settled on her shoulders. “You’ve been pushing yourself too hard.”

“It doesn’t matter how I push myself. I’m not getting anywhere,” she said bitterly.

André’s hands slid down her shoulders, rubbing up and down over her arms.

Something about the gesture made the tears prickle at the back of her eyes again. Laura’s legs were wobbly with the urge to sag back against André’s chest and let him hold her up, his arms around her, his warmth comforting her. He was so familiar by now, the feel of his arms, the smell of his skin, the very contours of his body. It would be so easy.

If she were an entirely different woman.

“You’re better than you were,” he said reassuringly. “People train all their lives for this. You can’t expect to pick it up in four days.”

“Five,” said Laura, to the playbill.

“Five, then.” She could hear the smile in his voice, as he gave her shoulders a squeeze. “Because that extra day makes all the difference.”

Shaking his hands off, Laura turned. Wedged between the wall and his body, she tilted her head up at him. “What if I ruin it for us all?” She couldn’t keep the despair from her voice. “The others must suspect already. What if one of them guesses the whole?”

“They won’t,” said André confidently, his hands resting on her shoulders. She could hear the crackle of the poster behind her back. Behind his spectacles, his eyes searched her face. One of the earpieces was crooked. “I told Harlequin—in confidence, of course—that you had been wardrobe mistress in our last troupe, but that I had promised you a chance onstage. That’s how we met, you know. You were measuring my tights.”

“You bribed me into your bed with the promise of a glorious career?”

“Something like that.”

“I’m flattered that you went to so much trouble to seduce me.”

“Don’t you think you’re worth it?”

Laura turned her head away. “Right now, I feel like the scrapings off the bottom of a carriage wheel.”

“That good?” André teased.

“The scrapings off the scrapings off the bottom of a carriage wheel.” She ducked under his arm, taking her paste pot and heading for the next stretch of wall.

This was clearly a popular stretch of wall for notices. New ones had been pinned over the decaying remains of the old. Laura brushed aside the tattered fringes of an advertisement for Berowne and his amazing dancing bears. She was glad they wouldn’t have to compete with that. Judging from the condition of the poster, the bears were probably hibernating by now. The placard next to it was of far more recent origin, the ink still bold and black, advising the good citizens of Beauvais that—

Laura groped for André, her fingers closing around his arm. “Look,” she croaked, dragging him over. “Look at this.”

“‘Wanted,’” he read. “‘André Jaouen, former assistant to the Prefect of Paris, for crimes against the state. Medium height, brown hair, spectacles. Likely traveling in the company of two children, a girl aged nine and a boy aged five.’ They gave Pierre-André an extra year.”

“That will make all the difference, I’m sure.” Fear brought out Laura’s sarcastic side.

André was studying the poster with more interest than alarm. “They don’t mention Jeannette or Daubier. Or you.”

“They didn’t need to mention Daubier. Look.” Pasted next to it was another poster. The Ministry of Police was also interested in any information as to the whereabouts of Antoine Daubier, painter. Elderly, obese, prone to brightly colored clothing, favoring his left hand.

That was one way to create an identifying characteristic: cripple a man before allowing him to escape.

Laura could feel sweat clammy under her arms.

“Well,” said André calmly. “It’s a good thing our posters are larger than theirs.”

Appropriating the paste pot from Laura, he slathered a generous portion of paste onto the back of a playbill and slapped it right over the two government notices. Laura was fairly sure that to do so was illegal. On the other hand, they were already illegal, so what was a little more illegality?

An outlaw. They were all outlaws.

The Commedia dell’Aruzzio’s advertisement completely covered the government notices, but Laura could still see the faint outline of print showing beneath the flimsy paper. One could attempt to paper over the past, but one could never eradicate it entirely.

“Those can’t be the only ones.” Laura’s fingers tightened on André’s sleeve. “You and the children. Someone might see these posters and recognize you.”

“I’m not the only man of middle height with brown hair in France,” said André sensibly. His eyes settled on her. “And the notice makes no mention of a wife.”

“But we’ve already determined that I’m no actress. What if I ruin it for us all? What if my incompetence means we’re caught?”

“Whether you like it or not,” said André lightly, “you’re part of the family now. We’d no more toss you out than we would Jeannette.”

“You don’t like Jeannette,” she said accusingly.

“But I’m very accustomed to her.”

“Don’t protect me simply because I’ve become a bad habit. I’m used to fending for myself. If it becomes necessary for the general good, I’ll go.”

“Where?”

“Into the sunset and far away.” There was no reason for the thought to be quite so depressing. They would have had to part ways once they got to England anyway. This fiction of being man and wife was just that, a fiction. She would do well to remember that. She was only here because the Pink Carnation had instructed her to see the Duc de Berry safely to England.

The recollection caught Laura up short. How long had it been since she had thought of the Pink Carnation? Or her obligation to the Duc de Berry? She had let herself get caught up in a fantasy, and this was the result of it.

“You’re willing to give up this quickly?”

“I’m not giving up. I’m reassessing based on the situation. You might do better without me.”

“Don’t fool yourself. You’re not the liability. I am. I’m the one Delaroche wants. None of us would be here if it weren’t for my missteps. And then there’s Daubier. But for me . . .”

The bitterness in André’s voice made Laura blink. She had seen him, over the past few days, frowning in Daubier’s direction, but she’d had no idea it had been weighing on him so.

She frowned up at him. “You’re not responsible for his hand.”

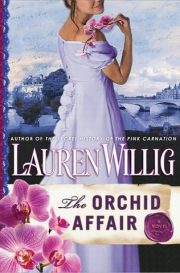

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.