Her neck hurt.

With a sigh, Laura rolled over again, trying to pummel the pillow into some semblance of comfort. The feathers had all but disintegrated with age. Whatever ducks had given their feathers for this pillow had died so long ago that their ponds had probably already silted over. The pillow felt like it was filled with grit. Maybe it was. Maybe she was just being difficult.

For heaven’s sake, why couldn’t she sleep?

“Laura?” The voice came from the next pillow over. It was little more than a murmur, but it sounded unnaturally loud in the small space.

Laura stiffened, instinctively playing dead. Was it too late to pretend to be asleep?

Punching the pillow had probably not been the brightest idea.

“Yes?” she said cautiously.

She could hear the rustle of blankets as he rolled over. Laura scooted even farther towards the end of the pallet.

“Is something wrong?” André’s voice was heavy with sleep.

Was something wrong? They were on the run through the countryside with two small children, a royal duke, and an injured painter in their care, and he wanted to know what was wrong?

“I can’t sleep,” she said, and felt like a child. A cranky, petulant child. What was wrong with her? She hadn’t been that sort of child when she was a child. “This bed is very . . . crunchy. And it’s cold.”

Better that than admitting the real reasons. And it was cold. She could feel the tip of her nose turning blue.

“What about you? Why aren’t you asleep?”

“I was,” André said pointedly. His jaws stretched in a long, uninhibited yawn. Hitching himself up a bit, he unfolded one arm, stretching it out along the top of the pallet. “Here.”

Here what? Laura could see the shadowy outline of his sleeve, pale against the darker skin beneath. He had elected to sleep in his shirt, the strings untied at the throat, the cuffs open and folded back along his forearms.

She, on the other hand, was still entirely fully clothed, with the sole exception of her shawl. That was another problem. Her blouse itched.

When she didn’t respond, André stretched out his fingers. “Come here.”

Laura regarded his arm suspiciously. His arm couldn’t possibly be less comfortable than the pillow. But... “Why?”

Although she couldn’t see very well, she was fairly certain that he rolled his eyes. “For warmth,” he said, “only for warmth. And because your fidgeting is keeping me awake.”

Laura lowered herself cautiously into the crook of his arm, from sheer fatigue, she told herself, rather than anything else. They both needed their sleep. “All right. But I don’t—”

His hand pressed against the back of her head, smushing her face against his chest.

“—fidget,” she said into his shirt.

“Mmph,” said André into her hair. It wasn’t so much agreement or disagreement as a shorthand for All right, that’s all very well, can we go to sleep now?

Shaking free of his hand, Laura turned her face so that she could breathe. Asphyxiation was seldom the route to a good night’s sleep. She could feel the rub of much-washed linen beneath her cheek—like an old sheet, she told herself. It was best for all concerned if she thought of him simply as an extension of the mattress. A much warmer and firmer portion of the mattress. In fact, he made a much better mattress than the mattress. Mattresses, after all, seldom came with their own heating agents.

She scooted gingerly closer, finding a comfortable spot somewhere below his arm and above his ribs.

André moved obligingly to make room for her, adjusting the angle of his arm around her shoulders and tucking his chin against the top of her head.

His shirt smelled of soap and spilled coffee, thin enough that she could feel the faint prickle of the hair on his chest.

“Better now?” he asked sleepily.

“Certainly warmer,” conceded Laura, and felt his chest rumble with something that might have been a chuckle.

“Good,” he murmured. She could feel the dip of his chin against her hair. “Sleep.”

To her own surprise, she did.

It wasn’t a rooster that woke them, but Harlequin, shouting with appalling cheerfulness, “Wake up, lovebirds! It’s morning!”

Laura blinked her gummy eyes open just in time to see his head disappearing back through the curtains. Doors. Doors were a good thing, she thought hazily. Much less permeable than curtains.

She yawned, feeling her eyes drift shut again, every fiber of her body resisting the imperative to wake up. She was heavenly warm and incredibly comfortable, curled up on her side, cradled in a nest of blankets. Laura stretched, and felt the blanket stir in response.

“Mmm?” said the blanket, and Laura came jarringly and fully awake.

That wasn’t a blanket, that was a man. A man with one arm under her head and another around her waist. At some point in the night, they must have rolled over, because they were sleeping like two spoons in a drawer, the curve of his body mirroring hers, her back tucked up intimately against his front.

Very intimately.

It had been some time since Laura had had personal experience of the more masculine portions of the male anatomy, but she was fairly sure that wasn’t his knee.

Laura bounded out of the bed, trailing half the blankets with her. Her blouse had come unmoored during the night, and she hastily yanked it back up over her shoulder.

“Good morning!” she babbled. “Time to wake up!”

André groaned, burying his head in the pillows, which all seemed to have bunched up on his side of the bed. Bizarre that there was already a “his” side and a “hers” side, but his side it was.

“Are you always this terrifyingly energetic in the mornings?” he inquired.

“No, it’s just a special treat for our first night together,” she snapped, then realized just what it sounded like. Deciding to quit while she was ahead, she said hastily, “Thank you. It was very kind of you to serve as pillow for me.”

André propped himself up on one elbow. “It wasn’t entirely selfless,” he said. “Where did you put my portmanteau?”

“There.” Laura pointed to the bundle she had packed for him. She did her best to sound nonchalant. “Not entirely selfless?”

André paused in the act of digging through the bag. He cocked a brow. “It stopped you thrashing about.”

Laura plunked down on the small stool in front of their one table. “I wasn’t thrashing. I was just . . . restless,” she said with dignity. “It’s been an unsettling few days.”

“No argument there.” André yanked his old shirt up over his head, revealing an expanse of chest lightly fuzzed with dark hair.

Laura swiveled around on the stool, reaching for her hairbrush. What with one thing and another, she had forgotten to braid her hair before going to bed, and it was a snarled mess. She attacked a chunk at random, wincing as the bristles hit knots. “Do you think Monsieur Delaroche is after us yet?”

André’s head emerged through the top of the fresh shirt. He pulled the ties together. “I would be very surprised if he weren’t. He’ll be itching to get his hands on Daubier.”

“And you,” Laura pointed out.

“And me,” André agreed.

“You seem surprisingly unconcerned.”

“I slept well.”

Laura made a face at him.

“I’m not unconcerned. Believe me,” André said with feeling, “I couldn’t be farther from unconcerned. But I did take some precautions before we left.”

Despite herself, Laura was intrigued. She lowered the hairbrush. “What sort of precautions?”

“I planted a few false trails. Delaroche should be getting reports of a man answering my description heading with two small children in the direction of Austria.”

“Austria?”

“In the fireplace of my study in the Hôtel de Bac are the charred remains of a series of letters with the Austrian foreign minister, bargaining for safe conduct. Such a pity the fire went out before it could burn down completely.”

“Isn’t that too obvious? Won’t he suspect?”

“Trust me, it’s very artful charring. He’ll also receive conflicting reports about a fishing boat.”

“Meaning,” said Laura, “that he’ll assume that the Austrian documents are a façade, but the fishing boat is worth following.”

André looked smug. “Or the other way around. Delaroche’s mind is just twisted enough to assume that the obvious falsehood must be real and the real-seeming option false. There should be enough there to keep him busy for some time. You, by the way, have accepted new employment in Provence and are on your way there even as we speak. It’s a very old family. And very hard to find, given that they died out two generations ago.”

“And Daubier?”

“Went to ground, presumably with Cadoudal. Someone is going to go to his studio to make it look as though he snuck back to get necessaries for himself.”

“Someone?”

“I do still have some friends in Paris. The point is that it ought to look as though we’re all in separate groups, with Daubier still somewhere in Paris. They won’t be looking for us all together, and certainly not here.”

“Unless Governor Murat saw,” Laura countered.

“After your extraordinary efforts to prevent him doing so?”

André’s voice was mild enough, but Laura felt a rush of warmth at the memory. After a night spent pressed together, body to body, it was absurd that the recollection of a bit of playacting could make her blush. That was all it had been, playacting.

Now, if only her body would remember that.

“There was nothing so extraordinary about it,” Laura muttered. “Anyone would have done the same.”

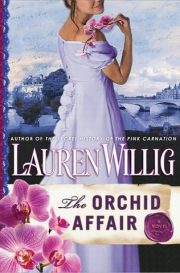

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.