They camped in the open that night. Cécile broached the decision as a money-saving measure—since some people, she added, with a pointed look at Rose, had been profligate with the group’s funds during their last stay, cutting into the troupe’s meager reserve.

The others had grumbled, but they had taken it as sense. Laura and André had exchanged a long look, silently giving thanks for Cécile’s acuity. At an inn, there would be other patrons, an innkeeper, witnesses to relay information should Delaroche catch the scent of their trail. It might be cold and damp, but it would be safe.

The wagons were arranged in a rough circle, creating some small protection from the wind. André set about unhitching and provisioning their mules while Laura woke the sleeping Gabrielle and Pierre-André. Odd that after a day he already thought of them as their mules, just as the wagon was their wagon.

Freed from the wagon, Gabrielle had gravitated towards Jeannette, hovering awkwardly as Jeannette wrested control of the cook pot from Cécile. Cranky at being woken, Pierre-André was being clingy and whiny, clutching at Laura’s neck. André could hear her speaking in a low, calming tone as she set him down, gently detaching his clutching fingers.

“. . . firewood,” she was saying. “Leandro is relying on you to help him.”

“Huh?” said Leandro, glowering at the Duc de Berry, who was helping Rose down from her wagon.

Even in the gloaming, André could see Laura roll her eyes. “You are relying on Pierre to help you gather firewood? Aren’t you? Leandro!”

“Oh! Yes. Of course, I am. A big fellow like you, er—”

“Pierre,” provided Laura. They had agreed it would be safer to drop the André. Pierre was common enough as a name, Pierre-André less so.

“Pierre, yes,” said Leandro hastily. He clumsily patted Pierre-André on the head. “How do you feel about gathering twigs?”

Laura crouched down to Pierre-André’s level “It’s an important job, carrying firewood. Do you think you’re up to it?”

They set out of the clearing together, the gangly Leandro nearly bent double as he held Pierre-André’s hand, Pierre-André assuring his new friend that he planned to gather more twigs than anyone ever. André caught himself smiling as he fastened the feed bag. Modesty wasn’t his son’s strong suit. Next to him, Leandro seemed hardly older, very earnestly explaining the most effective twig-gleaning techniques. André could see his son’s cowlick bobbing up and down in concentrated agreement.

Hauling the feed sack back into the wagon, André plunked it down next to the cookware, brushing his hands off against his breeches. Maybe, as counterintuitive as it seemed, this would be good for them. All of them together, in the same place, even if that place was a Commedia dell’Arte troupe. After the solitude of the Hôtel de Bac, a bit of companionship might not be a bad thing for Gabrielle and Pierre-André.

If only Delaroche didn’t come after them.

Pierre-André returned proudly bearing a pile of sodden twigs, while Leandro staggered under the weight of logs that looked as though they had been cadged, on the sly, from someone’s woodpile. André decided this wasn’t the time to be a stickler about such matters as private property. The rain had stopped but the temperature had dropped with it, leaving everyone both clammy and chilled.

The fire smoked and hissed, but it was still better than no fire at all. The small crew clustered around, getting as close to the blaze as space allowed, sitting on blankets and cushions taken from the wagons. Judging by the stains on the cushions, they had been used this way before. Jeannette, having established her place as Empress of the Hearth, ladled stew into wooden bowls. Sated, Pierre-André stretched out full-length across André’s and Laura’s laps, his head in Laura’s lap, his feet on André.

Low laughter came from the cushions on the other side of the fire, where de Berry was recounting a story for the delectation of the delectable Rose. A bawdy one, if the quality of her titters was anything to go by. Leandro moodily whittled a twig into a smaller twig. And next to him . . .

André poked Laura in the shoulder. “They look like they’re going to come to blows.”

Jeannette was standing over Daubier, hands on her hips. “—waste of perfectly good food.”

“I’m not hungry.”

“Nonsense,” said Jeannette stridently. “You’ve been traveling all day. You need your strength.”

Daubier’s face seemed to have collapsed in on itself, all hanging skin where there had once been ruddy flesh. “What for?”

Jeannette snorted. “What for? I offered you stew, not philosophy. Now eat!”

“Next she’s going to make him wash behind his ears,” murmured André.

Laura twisted her head to look at him. Her hair hung loose down her back, gypsy-style. “You’re enjoying this.”

The heel of one of Pierre-André’s boots was digging into one knee. The opposite thigh had gone to sleep under the weight of one compact four-year-old. The cushion under his backside was damp already, the wet seeping through the bottom of his breeches. André couldn’t remember the last time he had felt this relaxed.

Clearly, a sign that the strain had driven him mad.

There was something bizarrely soothing about sitting there in the uncertain light of the campfire, listening to Pantaloon pick out a tune on an instrument that looked like the descendant of a lute, sharing the weight of his son with the woman next to him, his daughter a few feet away, listening with rapt attention as Harlequin entertained her with tales of the Commedia dell’Arte. Now that the worst had happened, the anxieties that had gnawed at him since the children had come from Nantes seemed to have drained away, leached out in fatigue and the rough wine the actors had shared with their supper.

It was a false comfort, he knew. Delaroche was still out there; Daubier’s hand still needed tending; de Berry needed to be seen safely to the border. There were a thousand things that could still go wrong and a month in which they could do so.

But for now, for this moment in time, as Jeannette clucked over Daubier and Pierre-André permanently crippled his left knee and Laura Griscogne’s shawl tangled on his sleeve, yes, he was content.

Not enjoying himself, per se, but content.

“Jeannette never liked me, either,” he said blandly, deflecting the question. “It’s nice to see her go after someone else for a change.”

Gabrielle had elected to sit on her own cushion, her knees drawn up to her chest as she listened earnestly to Harlequin’s tales of the misadventures of the Commedia dell’Aruzzio.

Catching André’s eye over Gabrielle’s head, Harlequin winked. “Surely, your father must have stories of his own,” he said jovially, loud enough to be heard by the group. “We can’t be the only ones to have fallen afoul of the muses.”

André leaned back, resting his weight on the palms of his hands. “Which story do you want?”

Laura put a wifely hand on his arm. “Oh no. Once you get started . . . It’s late and the children should be in bed.”

Gabrielle gave Laura a look of death, not appreciating the reminder either of her youth or the lateness of the hour.

Struggling to his feet, Harlequin held out a hand to Gabrielle, sweeping her up. “Mademoiselle Malcontre,” he said grandly. “I trust you shall favor me again with your company tomorrow.”

His performance was such an obvious parody of de Berry’s that the others were hard put to repress their smiles. Gabrielle, however, ducked her head and bobbed a curtsy, taking the compliment very much at face value.

It all made André very glad that she was nine rather than nineteen.

Like a bird of prey, Jeannette descended upon them to sweep up Pierre-André, bearing him triumphantly forth as though he were her own personal prize. One by one, the others rose too, Harlequin taking the precaution of extinguishing the fire. Lanterns burned on their hooks on the sides of the wagon, casting a dim illumination over the clearing, by which the actors found their way to their own lodgings.

And beds.

André and his supposed wife were the only ones left by the smoking remains of the fire.

Rising awkwardly to his feet, André extended a hand to Laura. “Shall we?”

Ignoring his hand, she made a show of gathering up the blanket, which might have been more effective if she hadn’t still been sitting on it. André thought about pointing that out and decided it would only make a bad situation worse. She didn’t like to show weakness, his governess.

Laura hitched herself off the blanket and straggled to her feet, dragging up the blanket with her. “It is rather late,” she said, lurching down to grab the pillow. Her hair provided a screen for her face. “And we do have an early morning tomorrow.”

“Very early,” André agreed. “Dawn, most likely.”

He appropriated the pillow from her, tucking it under one arm, although he knew better than to offer his arm again. He held aside the heavy curtains screening the back of the wagon, making room for her to precede him.

“We should probably get some sleep,” she said, not looking at him.

The curtains dragged down behind him, shutting them into the narrow, dark chamber. The single lantern cast a dim light across the jumbled piles of cookware, the squat table, the pile of blankets. The bed.

“Yes,” André agreed. “Sleep.”

For a moment, neither of them said anything at all, both staring at the narrow pallet that was to be bed for both. One bed. One very narrow bed.

Then they both turned and started talking at once.

“Would you like—,” he began.

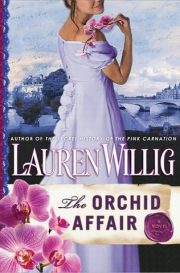

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.