André lowered his lips to her ear. “Was that wise? Telling him you were a governess? Rose may not be the only one with government connections.”

“I hardly think it will damn us. I’m not the only former governess in Paris. The closer we stay to the truth, the less likely we are to make mistakes.”

“Newlyweds?” said André.

“Aren’t we?” countered Laura. “I certainly never contemplated marriage to you before yesterday.”

“Fair point.” André’s tired face quirked into a smile. “You can’t get much more newlywed than that.”

His chin was stubbled with a day’s growth of beard and there were dark circles beneath his eyes. But there was something about that smile that made it impossible not to respond. Laura felt her chest clench with something she couldn’t quite identify.

“We’ll make this work,” she said softly. She hadn’t intended to. It just came out. “You’ll see.”

He looked down at her, comrade to comrade, equal to equal. His lips softened. “I rather think you’re right.”

Little bits of icy rain pecked at Laura’s cheeks. Why did she suddenly feel awkward? He was agreeing with her. Agreement was good.

Putting her nose in the air, Laura adopted her bossiest governess voice. “You ought to have realized by now, I’m always right.”

“Always?” He sounded not just amused, but . . . fond.

He was, Laura reminded herself, an excellent actor.

“Well . . . frequently,” she said hastily. “Oh, look, there’s Cécile.”

André gave her a funny look. “Yes, I could see that.” He inclined his head to their de facto troupe leader, who had been bustling about, arbitrating disputes and supervising disposition of baggage. “Madame Cécile?”

“No need to stand on formality, Cécile will do well enough,” said Cécile absently. “You have your baggage?”

“Yes,” Laura said calmly.

Laura had braved Jaouen’s lair, from which Jean had unceremoniously ceased guard, and bundled up linen, breeches, a brush, a shaving kit, a spare pair of spectacles. There had been precious little to choose between. His wardrobe was scanty and fairly repetitive. His room had revealed little in the way of secrets, other than a secret penchant for poetry. There had been a volume of Ronsard’s poems by his bed. She had been surprised to find that he read poetry still.

“We’ll have to find a wagon for you and the others,” Cécile was saying. “We’ve lost two, and there are eight of you. This may take some arranging.”

“Philippe had best come in with us,” said Harlequin, amiably enough, but there was a slightly malicious edge to his smile as he turned towards Leandro. “Leandro and I bunk together. We have grand times, don’t we, Leandro?”

“It’s well enough,” Leandro mumbled. He was too busy watching de Berry flirting with Rose, who might not want to waste herself on an actor but certainly wasn’t above accepting his skills as porter.

“Good,” said Cécile definitively. “That solves that. Monsieur Désormais, you can share with Pantaloon. Il Capitano and Ruffiana had their own wagon; that will go to Monsieur and Madame Malcontre.”

“And the children,” put in Laura.

The idea of sharing a wagon with André didn’t seem nearly as alarming with a wriggly Pierre-André in the middle, popping up and down half the night.

“Nonsense.” Jeannette elbowed her way in. “The children will stay with me. Just as they always have. The precious lambs will have nightmares without me.”

“The five of us, then!” said Laura. “One big, happy family.”

Cécile made a face. “There’s not really room, is there? Rose? Rose!” She snapped her fingers until Rose languidly turned her head, ribbons fluttering prettily. “If you give up your wagon to Jeannette and the children . . .”

“Me? Give up my wagon?” The threat to her privacy was enough to make Rose forget to put her best profile forward. “What about yours?”

“Either way,” said Cécile firmly, “we’ll have to share. Unless, of course, you’d rather take the children.”

Rose wrinkled her nose. “Why can’t they all go in with you?”

“Because,” said Cécile, in the tones of one dealing with a substandard child, “two and three makes far more sense than four and one.”

“That,” said de Berry gallantly, casting Rose a smoldering glance, “depends on the one.”

Leandro glowered.

Harlequin sighed.

Cécile rolled her eyes. “We’re settled, then. Rose will share with me; Jeannette and the children will have Rose’s wagon.”

“I really don’t mind having the children . . . ,” Laura began, but Cécile cut her off with a shake of the head.

It was a fleeting gesture, intended for Laura’s benefit only. Laura took the hint. Whatever her personal feelings about the woman, Cécile had her own reasons for wanting to keep Rose close. Given that Cécile was an associate of the Pink Carnation’s and Rose an associate (of an entirely different kind) of the Governor of Paris, it wasn’t, when she thought about it, altogether surprising.

Even if it did mean she had to share a wagon with André Jaouen.

Their wagon looked much the same as all the others—a rectangular structure hitched to two tired mules. There was a pallet on one side of the floor, a trunk that doubled as a makeshift table, and a haphazard miscellany of props and cookware jumbled into sacks. Whatever possessions the former Capitano and Ruffiana had owned had already been removed.

“Thank you for packing for me,” murmured André as he hauled her carpetbag and his bundles into a spare bit of corner between a pile of spare blankets and three Roman breastplates.

“I couldn’t let you traipse the countryside without a change of linen,” said Laura tartly.

That was an exceedingly small pallet.

Admittedly, it was also a fairly small wagon, but surely one could eke out a little more bed room than that.

“And Ronsard?” André held up a small volume bound in paisley paper covers and waggled it in her general direction.

Laura shrugged. Throwing the book into the bundle had been a whim. They were taking so little, after all. And there had been something about that marked page . . . Gather, gather, the rosebuds of today.

“More verisimilitude,” she lied. “I’d imagine that actors like poetry. It makes you seem more artistic.”

“If a little behind the times,” he agreed. He joined her in contemplating the pallet. “It is rather . . . small, isn’t it?”

Laura shook her hair back behind her shoulders. It felt very odd to have it so, practically unbound. “Don’t worry,” she said flippantly. “We can always put a naked sword down the middle.”

“That’s not what I—”

“Laura? André?” Cécile’s head appeared between the curtains at the back of the wagon. “We’re ready to go. I assume you can drive a wagon.”

André shook himself like a duck shaking off water and turned towards Cécile. “It’s been a few years, but I think I can manage.”

“Wait.” Laura grabbed at his arm, her nails scraping against his sleeve. It was a terrible sound. Wincing, she drew her hand away. “Hadn’t you better, um, take a nap? After your very late night of saying farewell to all your friends in Paris?”

“My very—ah.” He drew back, comprehension settling over his face.

André looked, for a moment, as though he might have liked to demur. It couldn’t, Laura imagined, be very pleasant to be smuggled out of Paris like a vat of wine, passively hiding inside a wagon while someone else did the driving. But there was no denying the validity of her concern. He had spent many years at the Prefecture. It wasn’t beyond the realm of reason that he might be known to the guards at the gates.

“Yes,” he said at last, although there was no mistaking the reluctance of it. “You might be right. I could use the rest.”

“You know how to drive?” Cécile asked Laura.

“I can manage,” she said, echoing André’s own words.

She had driven a dog cart during her governess days, and the odd trap. The mules attached to their wagon didn’t seem like terribly spirited beasts. It couldn’t be that hard to point them down the center of the road and make them go. She had no aspirations of driving to an inch.

She looked from André to Cécile. “If Jeannette can spare them, it might be nice to have the children sit on the box with me. Just until we’re outside of the city.”

She didn’t have to explain what she meant. There was nothing like children to lend an air of innocence to a scene.

“Naturally,” said Cécile blandly. “You wouldn’t want to be separated from your children.” Her head disappeared again between the curtains.

“So that’s what I’ve been reduced to,” André said grimly. “Using my children as shields.”

Laura paused in the act of following Cécile out of the wagon. “Don’t you know they’re glad to?” she said. “They love you, you fool.”

Before he could answer, she bunched up her skirts and followed Cécile out through the curtains.

They might no longer be employer and employee, but it still felt like lèse-majesté, calling him a fool. Even when he was being one.

If she had a family . . . Well, she hadn’t. Just a pretend one. She shouldn’t let herself forget that.

Outside, the other wagons had been loaded, the mules hitched up. It wasn’t an entirely inspiring sight. En masse, the general shabbiness was even more pronounced than it had been when the vehicles were scattered around the inn yard. Pantaloon sat on the box of one wagon, Harlequin another. Cécile climbed onto the box of the wagon she was to share with Rose, ably claiming the ribbons.

Pierre-André was snuggled next to Jeannette on the bench of the fourth, Gabrielle hunched beside them, cradling a book as another girl might have cuddled a doll.

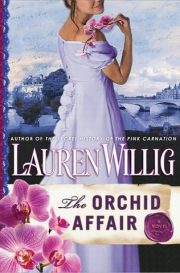

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.