“Or they’ll search the wrong one,” she countered. She navigated the narrow hallway with the ease of familiarity. “A dispute with the owner will occupy them for a spell.”

“You gave them a real address?” André almost ran into an ornamental urn.

Mlle. Griscogne’s eyes met his. “It seemed the expedient thing to do.”

Expedient? It was bloody brilliant. If there was a warehouse at the Rue des Puces, Laclos and Maugret could expect to be embroiled for some time with an indignant owner.

André yanked open the front door. “Who are you?”

Mlle. Griscogne slipped past him, through the open door, Jeanette’s old cloak pulled tight around her shoulders. “Laure Griscogne. A governess.” Two stairs down, she glanced back at him over her shoulder. “A friend to Monsieur Daubier.”

André shoved the door at de Berry, catching up with her halfway down the flight. “You expect me to believe you would involve yourself in treason for him?”

“Is that what this is? Treason?”

She automatically started towards the square as they reached the base of the stairs. André grabbed her arm, yanking her into safety in the shadows, de Berry following behind. “Don’t play games, Mademoiselle Griscogne,” he said in an undertone, careful not to wake the sleeping concierge. “They don’t suit you.”

Mlle. Griscogne’s voice was breathless from keeping pace with him. “Then deal with me honestly. Speak to me plainly.”

André kept a tight hold on her arm. “You want plain speaking? Your old friend Daubier is bound for the guillotine unless we can get him out.”

“There is no hope they will release him?”

“Intact? No.”

“Can you get him out?” she asked urgently.

“I can try.”

He could try, but he wasn’t sure he could succeed. Years of building up his position, and yet his influence only went so far. One false move, and he condemned not only Daubier but himself.

Jean wasn’t at the gate. André shoved it open himself, taking some solace in physical exertion, the simple act of pitting muscle against iron. If only it would be so easy to move the guards around Delaroche.

“In,” he said brusquely. “You’ll both stay here tonight. Cousin Philippe, make sure Mademoiselle Griscogne is well settled for the night.”

He could hear the gravel crackle beneath Mlle. Griscogne’s boots. “You mean you want him to guard me.”

“In plain language, yes. Would you do otherwise in my position?” He pulled open the front door, holding it open for her with exaggerated gallantry. The guests had long since gone home, the remnants of the feast been cleared away, the gauze torn down from the walls. The Hôtel de Bac was as it had been before—an empty, ruined shell of a place. “We have a great deal of talking to do, you and I.”

Mlle. Griscogne gave him a long look as she took up the candle that Jean had left on the front hall table. “I couldn’t agree more.”

A small voice piped up out of the shadows. “Mademoiselle?”

André saw a small figure huddled on the stairs.

“Pierre-André?” Pushing back her hood with her free hand, she moved quickly towards him. “What are you doing out of bed?”

Pierre-André stood on the first stair and wrapped his arms around her waist, burying his small head in her torso. “Nightmare,” he mumbled.

André took a step forward into the hall, feeling strangely out of place with his own son, in his own family. Pierre-André hadn’t seen him, he tried to reassure himself. Pierre-André would have come to him otherwise. Or would he? He had been little more than a stranger to his own children for the past four years.

And all for what? A plot that was fast unraveling, a cause to which his commitment was at best equivocal.

Mlle. Griscogne cupped Pierre-André’s head with a practiced hand. “What kind of nightmare?”

Pierre-André burrowed against her stomach. “We were on the bridge and that man—the man in the carriage—”

Mlle. Griscogne’s eyes met André’s over his son’s head. “Monsieur Delaroche.”

“He pushed me into the water. Hard,” Pierre-André added in injured tones. “I was drownding and drownding,” he said dramatically.

“But you’re not now,” said Mlle. Griscogne, in matter-of-fact tones. “You’re not in the Seine and you’re not on the bridge. You’re in your own house, all dry and safe.”

“Mmmph,” said Pierre-André.

She continued her rhythmic stroking of his hair. “It was only a dream, nothing more. It can’t hurt you.”

But Delaroche could. She knew it. André knew it. The worst nightmares were those that took place when one was awake.

Prising Pierre-André’s arms from around her waist, she leaned back just far enough to look André’s little boy in the eye. “I’ll put you back to bed, shall I?”

Pierre-André put up his arms and she hefted him up with surprising ease. André stood in the shadows, frozen, the full weight of what he might have done dragging at him like the waters of the Seine.

Pierre-André buried his downy head in the governess’s shoulder. She looked back to André. “I’ll be down directly.”

“I’m off to the Prefecture. I may be some time.” He added, with a flash of dry humor, “You needn’t wait up.”

Mlle. Griscogne’s eyes met his over his son’s tousled head. “But I will.”

Chapter 20

Laura started awake as boots sounded against the wood of the floor.

She hadn’t realized she’d fallen asleep. De Berry still snored peacefully away on his settee, one arm flung up along the back, but the candle had guttered into a puddle of wax and the pale light of dawn filtered through the windows. It was a particularly dispirited sort of dawn, as strained and gray as Jaouen’s face as he strode into the room.

Laura rose clumsily from her chair, aware that the fire had burned down long since, that her fingers were stiff with cold and her toes numb in her boots.

“Well?” she croaked. Her voice was dry with disuse. Laura cleared her throat and tried again. “What news?”

“It was no use.” Jaouen’s customary vitality appeared to have deserted him. He peeled off his glasses to rub his eyes, that gesture so familiar, and yet, like everything else, so suspect. “Fouché’s men have him under close watch.”

Laura wiped her palms against the rumpled material of her skirt. “I thought you were one of them,” she said tiredly. “Fouché’s men.”

She still hadn’t made sense of the fact that he wasn’t. The entire world had turned upside down and spun on its head in the space of the evening.

“I was.” Jaouen caught himself. “I am. For the moment.”

Until Fouché found out the truth.

What was the truth? Laura was too tired to sort out plots and counterplots. To her tired eyes, Jaouen seemed sincere. But then, she had believed him before, too, believed him to be whatever it was that he had claimed to be.

Laura sat back down, taking her time, using the motion as an excuse to study her so-called employer as she arranged her rumpled skirts with as much care as if they had been a princess’s best ball gown, her brain swimming with crosses and double crosses, deceptions and counterdeceptions.

In the mist-laden silence, de Berry made a snuffling noise and rolled over.

What did royal dukes dream of? Laura wondered irrelevantly. Castles and coronets? Swift horses and beautiful women?

Jaouen spoke, so abruptly that it made her jump. “I can get Daubier out. But if I do so, the game is up, for all of us.” Pressing his bloodshot eyes together, he breathed in deeply, shaking his head. “No. That’s a lie. It’s over already. It has been from the moment they arrested Picot. It’s only a matter of time now until it all unravels. And not much time.”

How did one tell the lies from the truths? She couldn’t be sure whether he was lying to himself or to her. Or both. His words had the ring of sincerity, but she no longer trusted her own ability to discern fact from fiction. At least, not where Jaouen was concerned.

“What are you going to do?” Laura asked quietly.

Jaouen dropped heavily into the chair next to hers. She could hear the scrape of the legs against the uncarpeted floor. He let his head fall back against the wall, as though it had grown too heavy to carry. “I can get him out,” he repeated. “I can go and present my cousin’s seal and claim that I’m moving Daubier on Fouché’s request. They’ll believe me. It’s been true often enough in the past. Once they discover the deception . . .” He let out his breath in a long, tired exhalation. “I’ll have to arrange for the children first. There’ll be preparations to be made.”

He spoke as though he didn’t expect to return. Laura twisted in her chair to face him. Her gray skirt brushed his leg. He was still wearing formal stockings and breeches, his garb from the party, but the white stockings were stained with mud, the shiny black shoes scuffed.

“And what about you?”

Jaouen rolled his head against the wall so he was facing her. His eyes were bloodshot and there was a night’s growth of beard on his chin. He said nothing.

He didn’t need to.

“You’re not just going to give yourself up,” Laura said disbelievingly. “Oh, for heaven’s sake! You are, aren’t you? Trading yourself in for Daubier? That’s something straight out of—out of a bad chivalric romance!”

Unless, of course, he knew himself to be in no danger, the more cynical part of her mind whispered. That would be clever, to free the old artist—at seeming risk of his own life—only to follow Daubier to his confederates.

“Of course, I’m not,” said Jaouen irritably. “What do you take me for, Robin Hood?”

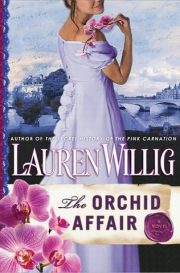

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.