Gallantry sat ill on him. Laura preferred him as he was, blunt and brisk.

Daubier pursed his lips. “Better, but still in want of work. Watch and learn, my boy, watch and learn. Your hand, if you please, my dear Laure.”

“You will return it, won’t you?” said Laura, holding out the requested appendage. “I do rather rely on it.”

“A loan only,” Daubier reassured her. “Now, André, watch how it’s done.”

Something in the way he said it made Laura suspect that he was talking about more than the rules of flirtation, but when she looked at Daubier, his rumpled face was as guileless as a child’s.

“I am all ears,” said Jaouen.

Daubier made a tsk noise before turning his attention back to Laura. With an elaborate flourish, he lowered his considerable bulk over Laura’s hand. She could hear his corset strings creak with the effort.

“My dearest lady,” he huffed, from somewhere in the vicinity of Laura’s knuckles. “I am rendered speechless by your . . .”

“Tidiness?” suggested Laura, as he paused for a noun.

Straightening with visible difficulty, Daubier gave her a reproachful look. “Look how little material you give me to work with. I do wish you wouldn’t dress like—”

“A governess?” Laura supplied. She meant it to come out lightly, but it sounded ungracious.

Jaouen broke the awkward silence. “Tonight you are not a governess.”

She had been a governess for so long, she scarcely knew what else to be. “Then what am I?”

Jaouen never faltered. “My guest.”

He meant it too. The simple decency of it staggered her. “Oh,” she said. “Thank you.”

Daubier, inattentive to by-play, was busy scrutinizing her dress. “It’s not the cut that’s the problem,” he muttered, “but the color. A bright crimson, that’s what you need. Something to bring out the tone of your skin and the luster in your hair. Something deep and rich. Silk velvet, not this drab stuff. Don’t you agree, Jaouen?”

Jaouen took in every aspect of her appearance, every scrap of fabric, every hair loose. “Crimson, indeed. Tyrian purple in the fine Roman fashion.”

“I hadn’t realized this was a costume party,” Laura babbled. “I could have come as something interesting. Like a tree.”

Jaouen’s lips turned up in a smile. “Botany, again, Mademoiselle Griscogne?”

“If I say I prefer nature to art, Monsieur Daubier will be offended.”

“But doesn’t art imitate nature?” Jaouen neatly turned the subject before she could retort. “Have you found the refreshment table yet?”

“I have,” said Daubier complacently. “High art, indeed. Excellent pastries. You should let André fetch some for you, my dear.”

Laura raised her brows. “The employer waiting on the employee?”

“Are you testing my egalitarian principles? Come along.” Jaouen held out an arm to her. “I’ll load a plate for you. Then perhaps you won’t doubt me again.”

Laura placed her fingers very tentatively on his arm. “Such drastic measures. Are you sure it’s worth it?”

“These are dangerous times, citoyenne,” he answered in kind, using the old Revolutionary address that had already all but fallen out of favor. “One can’t be too careful. Would you prefer sweets or savories?”

“Savories,” said Laura. “Sweets cloy.”

Jaouen raised a brow at her. “One could never accuse you of that.”

Behind them, Daubier beamed benevolently, a proud father sending his daughter off to her first ball. An illusion, Laura reminded herself, and a ridiculous one. Daubier had no daughters, and she made an unlikely debutante. She was thirty-two, not sixteen anymore. She was a working woman, not a girl from a fairy tale to be showered with belated blessings by a benevolent fairy godfather in a too-bright waistcoat.

On Jaouen’s arm, the crowd that had first ignored her fell away for her, clearing a path, nodding and smiling. Such was the power of the favored successor of the Minister of Police.

He looked his role tonight. Gone was the usual rough uniform of old breeches and a brown coat. Instead, he wore black, tailored to a nicety, with a snowy white stock and a waistcoat in maroon and silver—all in excellent taste and richly made. His rough hair had been brushed smooth, but the cowlick still stood stubbornly up in the back. Other than that, he looked what he was—the master of this establishment, magically transformed for one night from dilapidation to elegance.

Laura wished, foolishly and futilely, that she had put her hair up after all. Just one curl, one frivolous gesture.

Oh, no. She wasn’t meant to be thinking like this, and certainly not about her employer. It was only the fairy-tale trappings, she told herself—the ball, the candles, the prince.

Not a prince, she reminded herself. An employee of the Prefecture. The man on whom she was supposed to be spying.

Laura made to extract her arm from his, addressing him without any of the bantering tone. “I did mean it, what I said before. You needn’t waste your time on me. You have other guests who want tending to, I’m sure.”

Jaouen looked at her with amusement. “You don’t accept anything graciously, do you?”

“What do you mean?”

“Invitations, carriage rides, advances on your salary . . .”

“Would you have?” Gratuitous gifts generally made her wonder why they were being given.

Jaouen understood without being told. “No good deed without an ulterior motive?”

Laura wondered what his ulterior motives might be. Especially regarding her. “Do you disagree?”

“Not at all,” Jaouen agreed, tucking her hand more securely against his arm. “Most seeming acts of altruism tend to be motivated by something else. So much for the innate goodness of man.”

His cynicism didn’t ring true. She remembered the books in his study, the well-thumbed volumes of Rousseau and Sieyès. He had been a reformer once and, she suspected, an idealist.

“All right, then. If it’s not altruism, why waste your time with me?”

“Because it pleases me to do so. And”—Jaouen added—“because I would rather speak with you than the rest of this lot.” He eyed Augustus Whittlesby, garbed in the full splendor of flowing sleeves and artistically misbuttoned waistcoat, before adding prosaically, “I don’t much care for poets. Or poetry.”

Laura didn’t mention the volume in the nursery with his name on it. To Julie, who saw no use in poetry. “Why fill your house with them, then?”

Jaouen shrugged. “Julie started it. I keep them on for her sake. Vol-au-vent?”

Laura waved the pastry aside. “Is it always the same group?”

“It varies. Daubier generally attends—but I’m sure you expected that.”

“He never did like to miss a party,” murmured Laura.

“You speak of him in the past tense. As if he were no longer with us.” The candlelight danced along the rims of Jaouen’s spectacles, turning base metal to gold. He was watching her too closely for comfort, picking her apart like the subject of one of his reports.

Laura shrugged uncomfortably. “That’s what he was to me, part of my past. I haven’t seen him for sixteen years. You would have used the past tense too.”

He watched her, saying nothing, waiting for her to go on. An old technique, and an effective one.

Laura hastily changed the subject, gesturing out into the room at large. “Who are all these others? You don’t expect me to believe that he’s a poet.” Laura indicated a prosperous-looking man with long gray side-burns. “Or she.”

She pointed to the Pink Carnation, sitting with her hands folded in her lap, serenely accepting the accolades of a young man with wildly disordered hair. Another agent? Or a genuine admirer?

Apparently, it was the fashion to be in love with Miss Wooliston.

Jaouen’s eyes passed over Miss Wooliston without interest. “He is a speculator in army contracts. A successful one. She, I believe, is the cousin of one of Bonaparte’s courtiers.”

His seeming casualness didn’t fool her. She would be willing to wager he owned complete dossiers on each one. “Why invite them to your salons? They’re hardly likely to paint the Sistine Chapel.”

“Neither did Pope Sixtus. Where would artists be without patrons to pay them? All of the people in this room serve each other in some way. The beautiful young ladies play muse to their pet poets, and the elderly financiers pay for the pigments of the painters. They rely upon one another.”

“So you bring them together.” Laura raised a brow. “How very altruistic of you.”

“Are you trying to catch me out, Mademoiselle Griscogne?”

For a moment, Laura sensed something beneath the bantering question, a hint of real wariness. But it was gone before she could catch it, hidden beneath the shimmering, shifting play of light on the glass that armed Jaouen’s eyes.

“Well?” asked Laura daringly. “If there is no altruism, what is your motive for these gatherings?”

“Not the sonnets,” Jaouen said dryly. Without discussion, they resumed their progress, walking arm in arm through the throng. Jaouen nodded in response to the greetings of a group of ladies but didn’t stop. “Call it inertia rather than altruism. These gatherings were Daubier’s idea originally, when Julie was first exhibiting. He held them in his studio.”

“In the Place Royale,” supplied Laura.

Jaouen glanced down at her. “Were you there? I should think I would have remembered.”

“No. Those gatherings must have started after—well, after.”

After England. She had come close to giving herself away there. She mustn’t forget who he was, no matter how amiable he was making himself.

No matter how much she enjoyed his company.

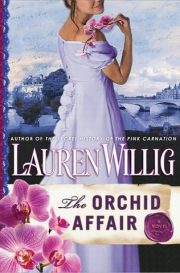

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.