For all his practiced bonhomie, Daubier could be infuriatingly close-lipped when he wanted to be. Laura supposed he had to be, with all the secrets that came out over long portrait sittings, but she could hardly count it a virtue when she was the one questioning rather than concealing.

Daubier forestalled further questions by taking her hands into his, as he had long ago with the small child she had been when he had helped her up onto the plinth for her portrait. Even though she was a great deal older now, the gesture made Laura feel small again—small and cherished.

“If you change your mind, you know where to find me.”

Laura smiled up at Daubier, feeling the sun glint against the tips of her eyelashes. Looking into his lined old face, as wrinkled and red as an apple, she felt a surge of affection for him, for all the memories she had all but forgotten and for his clumsy attempt at reparations now.

It was nice to have someone who might be just a little bit on one’s side.

“You’re not still in the old studio, are you?” There it was again, memory, coming back after all this time: sunlight slanting across a honey-colored floor, a green velvet drape cloth nubby to the touch, the prickle of tiny claws against her fingers.

“Yes, in the Place Royale. Having found a place I liked, I saw no reason to leave it.”

Laura marveled at the wonderful sameness of it all. It was nice to know that some things remained the same, and that, come what may, through riot, revolution, and assorted new regimes, M. Antoine Daubier could still be found with brush in hand in the third-floor apartment in the southeast corner of the Place Royale.

Then Daubier ruined it all by saying, with a squeeze of her hands, “Do be careful, my dear. For your parents’ sake.” He reached up a hand to tap her cheek. “And for your own.”

“Oy!” a surly Jean poked his nose through the bars of the gate, reluctantly executing his office as gatekeeper. “It’s you, is it?”

Jean spat into the gravel. Laura recognized this as his hello, how are you? spit.

“Good evening, Jean,” she said, extracting her hands from Daubier’s grasp. So much for emotional reunions. “Would you care to open the gate for me?”

The early dark of winter was beginning to fall, slanting across the building to cast a shadow across the court, so that while the street outside the gate was still in full sun, the courtyard brooded in shadow.

A bird perched above the porte cochere, rooting with its beak among its feathers. Its feathers were a deep, unrelieved black.

Naturally. It would be a raven.

Jean made a great production of hauling open the huge iron doors. “He coming in too?” he demanded, launching another wad of phlegm at Daubier. His supply seemed to be inexhaustible. Laura wondered that the First Consul didn’t deploy him against the Austrians. That would be one way to damp their cannon.

“No, no.” Daubier took a step back, lifting his hands in negation. The raven shifted restlessly on the roof, eyeing the shiny top of Daubier’s cane.

“Will you be all right?” said Laura, thinking of the old man alone, on foot, in the dark. “Perhaps you should take the carriage?”

“No need,” said Daubier. “These old legs can still bear me up. But . . .”

He broke off as Jean slammed the gate between them, metal hitting metal with an ominous clang. Daubier drew in a sharp breath through his nose. Coming straight up to the gate, he rested his hands on the ornate grille, his nose sticking through a particularly swirly curlicue. It ought to have looked comic, but the worry in his eyes killed any appearance of comedy.

“Take care,” Daubier said somberly. “Take care. And remember. If you need me, you know where to find me.”

Overhead, the raven cawed.

Chapter 12

“You should be more careful of the company you keep, Jaouen.”

Despite the sunlight falling through the window, Delaroche managed to keep to the shadows in his side of the carriage. It was almost as though the dark recognized a kindred soul and knit itself around him.

André stretched his legs comfortably in front of him and managed a credible yawn. “Governesses, you mean?” he said. “Surely I could hardly do better than to follow your example.”

Delaroche’s eyes glinted like a rat’s. “Sometimes even the teacher can be taught.”

Not this teacher. André would have laughed if it hadn’t been so important to keep Delaroche on a short string. He would have been more likely to suspect his governess of subversion had Delaroche not gone to such pains to make him do so. If the governess were really Delaroche’s creature, the man would be a fool to draw attention to it. He was just trying to sow discord and dissension, as usual. It was what he did.

Delaroche was slipping, thought André critically. This really wasn’t up to his usual standard.

Of course, it could all be a clever double-fake—if Delaroche were that clever. But Delaroche wasn’t that clever, and his governess wasn’t that malleable. Judging from their prior interactions, André would have been willing to attest that Mlle. Griscogne was about as ripe for subversion as a balky mule.

Still, everyone had her price. It wasn’t outside the realm of possibility that his governess was on Delaroche’s payroll. Logic told André that it was perfectly likely. Gut instinct told him otherwise.

Over the years, André had learned to trust his gut.

Was he being foolish, allowing himself to be swayed by the fact that she had known Julie’s old teacher, or that she had been, once, a very long time ago, the Girl with the Finch?

That painting had been one of Julie’s favorites, although her own style had been grander, bolder, and more inclined towards vast allegorical topics than the narrow and domestic world of Daubier’s portraiture. Against a plain background, the painting depicted a dark-haired little girl in a white dress with a bright orange sash and a finch perched on one raised hand so that she seemed in colloquy with the bird. The most striking thing about the portrait had been the girl’s expression. Her dark eyes had been bright with curiosity as she contemplated the bird. The portrait had been hailed as a representation of the unbounded possibilities of the human intellect in a world of natural wonders, a popular theme in those bright days before the world had burst into smoke and blood.

André wondered if his governess knew that she had become a pre-Revolutionary icon, a symbol of the lost dreams of the Enlightenment. The girl with a finch, who had now become . . . what? The woman with a crow? A spy for the Ministry of Police?

Or simply what she claimed to be, a woman alone, orphaned, making her way as best she could in an inhospitable world, and doing a damned good job of it.

André forced himself to adopt a suitably bored tone. “Have you been essaying lessons, Gaston?”

Delaroche hated it when André called him by his first name, which was exactly why he did it. Baiting Delaroche involved a delicate balance; one had to goad him just enough to maintain the balance of power, but not enough to provoke him into overt retaliation. Even hobbled, Delaroche was a dangerous enemy to have.

Was there anyone who wasn’t? thought André wearily. His world was a snake pit, in which even the smallest serpent’s venom could prove deadly.

“I wasn’t thinking of the governess,” said Delaroche, licking his lips in a way that suggested he had an even better card to play. “I was speaking of artists. Painters, poets, actors. Like that friend of yours. The one in the flamboyant jacket.”

“I don’t know any actors, actually,” André said, examining the seams of his gloves. “A lamentable oversight. As you know, Fouché has entrusted me with the monitoring of the artistic community. Such as it is.”

How Julie would object if she knew that was her legacy, her connections with the artistic community used as a means of gathering intelligence for her least-favorite cousin. Once a month, André threw an open house in the grand and deserted salons of the Hôtel de Bac, inviting painters, poets, philosophers, and the ladies who patronized them. Sometimes they recited; sometimes they displayed their work; other times they just drank.

Fouché never attended. That would destroy the illusion that it was nothing more than a social occasion. A tattered illusion, but a useful one, nonetheless.

“I would be wary of spending too much time with them,” Delaroche shot back. “Lest their habits rub off on you.”

“What habits might those be?” André asked. “Good taste? Proper diction?”

Delaroche’s eyes narrowed. “Improper allegiances, you mean. There have been rumors about your friend, that Monsieur Daubier.”

“Yes, I know,” said André. “I’ve heard them too. A cause for congratulation, don’t you agree, that he should be chosen by the First Consul to paint his portrait? It is not an honor extended to everyone.”

“For good reason.” Delaroche rested his palms on his knees as he leaned forward. “Someone allowed such intimate access to the First Consul might succumb to the temptation to treason.”

“What are you saying, Delaroche?”

Delaroche smiled a nasty smile. “Exactly what it seems. Your friend has been known to accept commissions from unregenerate members of the Ancien Regime.”

“All of whom are now accepted at the First Consul’s court,” André said acidly. Bonaparte and his wife had been assiduously courting the old aristocracy, seeking to add some luster to their increasingly pseudo-regal arrangements. “Daubier’s paintings helped make the Revolution. You can’t possibly mean to imply—”

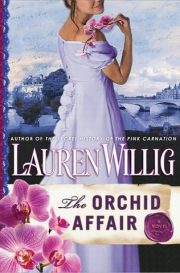

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.