Jaouen grimaced. “Forgive me,” he said. Ripping open the paper, he shook the white powder into his coffee. “I work all day in conditions that—let us say that they do not encourage delicacy.”

Laura watched the white powder dissolving into the coffee. “There is no need for delicacy. I may spend my days in the schoolroom, but I am no schoolgirl.”

“No. I can see that.” Jaouen’s attention fixed on Laura with a suddenness and intensity that felt like a stab to the stomach with Miss Gwen’s parasol.

So that was the trick of it, thought Laura dizzily. A totality of concentration, fixed on one object at any given time. Whatever task André Jaouen had at hand, he gave it his entire and unbroken concentration. To be on the receiving end of that was, to say the least, jarring.

He shrugged, breaking the connection. “Even so. What did Delaroche say to you?”

Laura scrambled to recall herself. “He greeted the children by name.”

Jaouen gave another of those quick, keen looks, like the flash of a bird’s wing on a summer day. “He recognized them?”

Laura frowned, remembering. “He recognized Gabrielle. He called to her by name first.”

Jaouen cursed again, but softly this time.

Laura held up a hand. “You needn’t bother apologizing. Monsieur Delaroche said he was a colleague of yours. He offered us a ride in his carriage.”

Jaouen pierced her with his gaze. “Which you did not accept.”

“I did not know if you wished to encourage the association.”

There had been something off about the man, something that made the hairs on the back of her neck prickle. She didn’t mention that bit. Prickling hairs were hardly a guide for conduct. Next she would be consulting the entrails of birds, like the Ancient Romans.

Jaouen let out a quick, sharp exhalation. “Well done.” Seeming to realize that some explanation was called for, he said briefly, “I prefer not to mix my professional obligations with my familial ones.”

That was his explanation? Laura had heard better from four-year-olds with jam still smeared across their faces and bits of broken tart in their laps.

Jaouen tapped his finger against the side of the coffee cup.

Drink, thought Laura. Drink, already.

He didn’t.

“You did well to tell me of this.”

“Is there anyone else I should know to avoid?” Laura asked quietly. “Or from whom the children should be kept?”

Jaouen grimaced. “Everyone?”

Laura suspected he wasn’t entirely joking. “Shall I bring you anything else? Bread, cheese?” More sleeping powder? “Your coffee must be getting cold. I can bring you a fresh pot.”

He didn’t take the hint. The cup sat untouched, steam curling harmlessly into the air, cooling by the moment, the precious powder wasted, of use only to the bright-winged cockatoo drowned at the bottom of the cup. Laura hoped it, at least, was enjoying a good slumber.

“No need.” Jaouen sketched a quick, impatient gesture. “I didn’t hire you to play housemaid.”

“Someone has to.”

Jaouen rocked back in his chair. “Are you saying my staff is inadequate?”

“Woefully.”

“Jeannette keeps the nursery clean and comfortable,” he said, as though that were all that mattered.

“What about the rest of the house? What about you?”

Jaouen lifted both brows. “We good servants of the Revolution have no need for the baser creature comforts.”

Laura drew a finger along the edge of the desk, collecting a little pile of dust as she went. “Brutus may have been a brave man, but dust still made him sneeze.”

“Are you offering to ply the duster?”

“I’m offering to interview the maids.”

“Unnecessary,” said Jaouen. “I only entertain guests once a fortnight, and I have a hired staff who come specially. As for the rest”—with one precise flick of the finger, he made short work of Laura’s dust pile—“if to dust we must go, I can scarcely object to a bit of it on my desk.”

“One might as well say that since we are bound for the grave, we ought to take our rest in a coffin.”

“Sophistry, Mademoiselle Griscogne.” But she sensed that he was enjoying himself. He was sitting up straighter in his chair, a light in his eyes despite the purple bags beneath them. “Is that what you intend to teach my children?”

“Rhetoric, Monsieur Jaouen,” Laura corrected. “And I shall, as soon as I have the proper texts at my disposal.”

“Heaven help us.” His hand hovered for a moment over the coffee cup and went instead to the papers, which he shuffled in a way that signified the interview was over.

Why wouldn’t he drink?

“Will there be anything else?” Laura asked in desperation. How could she time the action of the drug if she didn’t see him imbibe it?

He looked up, abstractedly, a piece of paper half-lifted. Laura tried to read sideways, but all she could make out were the words “question,” “asked,” and something that looked a bit like “squirrel,” but couldn’t be unless the new administration was now after nuts.

“Tell the children I wish them a good night.” He thought for a moment and came up with, “Wish them sweet dreams.”

There was no way she could eke this out further. “Yes, sir.” She curtsied.

“Mademoiselle?” Jaouen’s voice rose behind her. “There is one last thing.”

“Sir?”

“Don’t curtsy,” he said. “It doesn’t suit you.”

And he turned back to his papers.

Laura would have curtsied to cover her confusion, but apparently it didn’t suit her. She lurched for the doorway, only to come up hard against something that wasn’t doorlike at all, although it did have the effect of arresting her progress and knocking the breath out of her. Laura found herself blinking into an expanse of blue wool, adorned with very hard and very shiny silver buttons.

“Oh, I say!” exclaimed a male voice that was obviously not Jean the gatekeeper’s, any more than that coat could belong to Jean the gatekeeper. It was a plummy, well-educated male voice. A large pair of hands reached out to catch her by the hips, although whether to steady her or assess her contours was unclear. Her contours must have passed muster, because the hands lingered. He gave a good squeeze. “I am sorry. Didn’t expect to see anyone coming out of there.”

The hands were well manicured, with smooth nails and a smattering of fair hair along the backs. They were attached to a large young man in a regimental uniform, light brown hair brushed to a sheen above a pair of ruddy cheeks in a fair-skinned face.

“No harm done,” said Laura crisply, twisting away.

“I should hate to be the cause of a lady’s distress.” The young man smiled roguishly down at her in a way that suggested he was more accustomed to causing distress than relieving it.

“The governess,” stressed Laura, “is unharmed and thanks you for your kind attentions.”

“Ah.” Instead of being deterred, the young man propped an arm up on the wall above her head. “So you’re the new governess. I must say, you’re a sight better looking than Jeannette.”

Hard to feel flattered when that was the comparison. “Thank you. Sir.”

“Philippe?”

Behind them, the chair scraped against the wooden floor. Jaouen stood with one hand braced on the desk, frowning at the new arrival. The young man’s polished appearance only served to emphasize Jaouen’s rumpled clothes and unshaven cheeks. The twin lines in his forehead grew deeper as he looked at his guest.

He did not seem pleased to see him.

“Hullo, Cousin André!” said the young man boisterously. “Aren’t you glad to see me?”

If he couldn’t tell the answer to that just from looking at Jaouen, there was no helping him.

Of course, thought Laura. This was the cousin Jaouen had mentioned during her abortive interview. She began to understand why Jaouen had warned her about him. The young man was certainly well favored, and carried with him an air of aristocratic insouciance that suggested that he was used to receiving whatever he desired—a category that included the female staff. This was one who would always choose ease over effort, convenience over conquest. It was hard to imagine anyone less like Jaouen. This man’s uniform looked like it was more for parade than service and his hair was as buffed as his buttons.

“I thought you were rejoining your regiment,” said Jaouen, and there was a warning note in his voice that even Laura couldn’t miss.

“I didn’t want to miss all the fun in Paris,” said the young man cheerfully. “It’s much more exciting here.”

Jaouen was not amused. “It won’t be so exciting when you’re courtmartialed for desertion. Did you think of that? How would your poor mother feel?”

“Gloomy, gloomy, Cousin André.” The young man sauntered over to the desk. There were two bright red spots in his cheeks that might have been from the wind or wine or a bit of both. “I have more faith in my stars than that.”

“The stars have been known to shine on others before this. There is no need to actively encourage them to do so.”

“Not my stars.” Seizing Jaouen’s coffee cup, he hoisted it in an exuberant toast. “How go the plans for the fête?” Dark drops of drugged coffee sloshed over the sides and onto Jaouen’s papers. Any moment now, and the desk would be snoring.

No, Laura thought. No, no, no.

Reaching up, Jaouen snagged the cup, placing it firmly back on its saucer. “The fête may need to be postponed.”

“Postponed!” Philippe shot up with all the indignation of a young child denied a treat.

Jaouen pressed his eyes tightly closed for a moment before turning to Laura. “You may go, Mademoiselle Griscogne. I wouldn’t want to keep you from the children.”

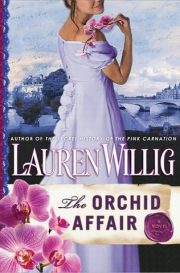

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.