“And a copy of Caesar’s Wars,” Laura said brusquely as the shopkeeper set down Hercules on top of the botanical treatise.

What was the Pink Carnation playing at? She had known Laura intended to come to the bookshop today; in fact, it was she who had advised her to do so. Why come bearing a Bonaparte? Laura didn’t like surprises, especially not in Bonaparte form.

“Gallic or Civil?” asked the shopkeeper laconically.

“Civil—no, Gallic,” Laura corrected herself.

What was the Pink Carnation doing going about with a Bonaparte on her arm?

Laura supposed it must be an equivalent of the old adage about keeping one’s enemies closer. When it came down to it, it wasn’t all that different from her notion of bringing the children along to provide an air of innocence. No one would ever suspect Miss Wooliston of delivering or receiving treasonous material with a daughter of the First Consul in tow.

Laura might have been teaching for what felt like an eon, but when it came to espionage, she still had a great deal to learn.

“No cannonade more powerful than the grapeshot of your eyes!” declaimed the poet. “No fusillade could match the artillery of your wit, no cavalry charge the pounding of the hearts which beat only for you!”

“We really must get you near a proper battlefield, Monsieur Whittlesby,” said Bonaparte’s stepdaughter with amusement. “Or at least buy you a book on tactics to bolster your metaphors.”

“Ought you to be encouraging him?” Holding out a hand to the poet, Miss Wooliston said, “Give me that ode of yours, Mr. Whittlesby, and from now on apply your pen to worthier subjects.”

Whittlesby gazed up at her soulfully. “What topic could be worthier than love?”

“Digestion,” snapped the older woman without a moment’s reflection.

“Digestion?” Whittlesby clutched his poem protectively to his chest and looked askance at the woman in the purple plumes. “My words are meant to be savored with the eye, not the tongue, Mademoiselle Gwendolyn.”

“I don’t believe she was planning to eat them, Monsieur Whittlesby,” said Hortense Bonaparte reassuringly, patting the poet’s sleeve. “Nobody’s teeth are that good.”

Mademoiselle Gwendolyn, or, in plain English, Miss Gwen, bared a set of teeth that gave the lie to Hortense Bonaparte’s supposition. “You can mock all you like, but that doesn’t change facts. Just look at the chronicles of history here in this shop! The Roman Empire was lost by rich sauces, not by love.”

There was an idea, thought Laura. If all else failed, they could simply feed Bonaparte into submission, one cream puff at a time.

Considering that she had proved her point, the Pink Carnation’s chaperone directed a look of withering scorn at the poet. “Attend to your diet before you talk to me of poetry.”

Whittlesby made a valiant effort to rally. “But poetry is food for the soul!”

“Hmph. If that’s true, your poetry wants fiber. Your adjectives are flabby and your nouns lack substance.”

Radiating offense, the poet made a show of extending the roll of paper past Miss Gwen, into the waiting hand of Miss Wooliston. “I shall let my muse be the judge of that,” he said sniffily. “Good day.”

“Good day, bad poetry!” Miss Gwen called triumphantly after him. The door closed with a decidedly unpoetic bang.

Hortense Bonaparte stifled a smile behind one gloved hand. “Must you torment him so, Mademoiselle Meadows?”

Miss Gwen was unrepentant. “Anyone who writes drivel such as that deserves to have the stuffing knocked out of him. An eye for an eye, I say.”

“Or an insult for an ode?” Miss Wooliston unrolled roughly two inches of her ode. “Oh, dear. He’s gone and compared me to a graceful gazelle gliding gallantly o’er a glassy glade again.” Shaking her head, she rolled it tightly back up. “If he must show his admiration, it’s a pity he can’t just do it with flowers.”

“Roses,” suggested Hortense Bonaparte, whose mother had made an art of cultivating them.

Miss Wooliston tilted her head, as though considering. “I have always been rather partial to carnations.”

“Cheap, showy things,” Miss Gwen said with a sniff. “Rather like that Whittlesby’s poetry.”

“At least he hasn’t published any of his odes to you in the newspapers yet,” contributed Hortense Bonaparte, cheerfully oblivious to botanical subtext. She slid her arm companionably through the Pink Carnation’s. “One dreadful little man did that to me while I was still at Madame Cam-pan’s school. The other girls called me la Belle Hortense for weeks. It was very trying.” Glancing over a display of books as she spoke, she lifted a large volume bound in red morocco from the table, angling it towards Miss Wooliston. “Have you read this yet? I heard it was rather good.”

The Pink Carnation shook her head, making a show of looking around the shop. “I was hoping to find a copy of The Children of the Abbey.”

“Do you mean to tell me there is a horrid novel you haven’t read?” Mme. Bonaparte feigned shock. “I thought you had them all.”

It struck Laura that the Pink Carnation was on remarkably good terms with the First Consul’s stepdaughter. Well, what had she expected? That the Pink Carnation would conduct her career by skulking in dark alleys in malodorous disguises? It was much more efficient to do one’s reconnaissance in a drawing room, properly garbed.

Miss Wooliston accepted the teasing in good grace. “I seem to have missed this one, and I am most distraught about it. Who knows what might be hidden behind those abbey walls? I simply must find out.”

An abbey or an Abbaye?

Taking Miss Wooliston’s statement at face value, Mme. Bonaparte laughed good-naturedly. “I shouldn’t imagine you’ll find anything out of the ordinary. Aren’t those novels all the same?”

Miss Gwen let out a loud and offended harrumph that set her plumes a-wagging. “Only to the uninformed. How many have you read recently, missy?”

Mme. Bonaparte held out her hands in a gesture of defeat. “I was once very fond of La Nouvelle Héloïse.”

“Ha!” exclaimed Miss Gwen. “That drivel! That Rousseau wouldn’t know a proper plot if it bit him.”

Mme. Bonaparte bowed her head in contrition. “I shall eagerly await the publication of your romance, Mademoiselle Meadows.”

“In the meantime,” said Miss Wooliston, neatly bringing the conversation back around. “I must have my Children of the Abbey. I find I am become quite urgent in my curiosity.”

She said it in such a droll way that Mme. Bonaparte laughed, but Laura sensed a deeper purpose. “What do you expect to find?”

Miss Wooliston waved a dismissive hand. “Oh, the usual horrors, as you said. Ghosts, ghouls, strange reversals of fortune, lost princes. . . .”

Was it Laura’s imagination, or had there been an additional emphasis on that last phrase?

“Strange things can happen in abbeys on dark and stormy nights—much like last night.” The Pink Carnation added prosaically, “That must have been what put me in the mood for it.”

Last night. Last night, after their interview, she had heard M. Jaouen direct his coachman to the Abbaye Prison. Something must have happened at the Abbey last night, something the Pink Carnation most urgently wanted to know.

“You couldn’t be satisfied by Otranto?” suggested Mme. Bonaparte with a smile.

“I find I grow weary of my old books.” Miss Wooliston made a face. “I crave more mysterious mysteries and more villainous villains.”

Mme. Bonaparte looked slyly at her friend from beneath her bonnet brim. “What about more heroic heroes?”

The Pink Carnation raised both eyebrows. “Do you know any?” she asked dryly, and Mme. Bonaparte laughed.

“Will that be all?” the shopkeeper asked. It took Laura a moment to realize that he was speaking to her.

Laura hastily reached for her reticule, grateful that the Selwicks had made her take a course on currency at their spy school. She had sorted and resorted sous and louis and livres until she could fumble them out in their correct denominations in her sleep.

“Yes, we’ll have the myths, the Gallic Wars, the botanical treatise and—did you find something, Gabrielle?” she asked, looking down at Gabrielle, who was standing next to her, with a book folded protectively to her chest.

Silently, Gabrielle extended the volume. It was discreetly bound in dark leather, but the title belied the demure exterior. Like the Pink Carnation, Laura’s new charge appeared to have a taste for horrid novels.

Laura took the volume from her, a French translation of Mrs. Radcliffe’s The Romance of the Forest. “Does your father let you read this?”

Gabrielle hunched her shoulders defensively. “Grandfather did.”

Laura turned the volume over in her hands, giving Gabrielle time to squirm. “I see no problem with your wallowing in ghosts and ghouls so long as you apply yourself to your lessons first.” Laura plunked Gabrielle’s book down on top of Caesar. “We’ll have that as well.”

“You can return it, if it doesn’t suit,” said the shopkeeper. “Just make sure you include the reckoning.”

“Shopkeep!” Miss Gwen pushed past Laura, waving her furled parasol in the air. “Sirrah!”

Pierre-André stared, fascinated, up at Miss Gwen’s headdress. “I like your feathers.”

Miss Gwen favored the small boy with an approving look, an expression that involved the most marginal relaxation in her habitual scowl. “It is reassuring to find that someone in this benighted city has a sense of fashion.” She wagged a finger at the boy. “Never let them tell you otherwise.”

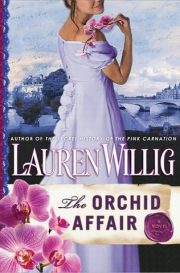

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.