‘You must be mistaken.’ His efforts to keep his voice neutral were only partly successful. ‘She sailed with Heini on the Mauretania at the end of July.’

‘No, she didn’t. Heini sailed, but Ruth didn’t. She told me in her letter.’

‘Where is she, then?’

Another decision to make… but this new and confident Pilly made it.

‘She’s somewhere in the North of England working as a mother’s help.’

‘What! No, you must have got that wrong.’

Pilly shook her head. ‘I haven’t. And I’m very worried about her. I don’t understand what’s happening. She keeps saying she’s all right, but she isn’t — I know she isn’t. She’s unhappy and in a mess… and I think she’s being silly.’

‘What do you mean?’

Pilly, waiting at a crossroads, tried to explain. ‘I love Ruth,’ she said. ‘I really love her. It’s because of her I got my degree, but that isn’t why. She made life… big for me. For all of us. Important, not petty. But sometimes suddenly she’d behave like someone in a book or an opera. Like she did when she was trying to give herself to Heini. All that business about being like La Traviata or that girl with a muff. Love isn’t about operas,’ said Pilly — and smiled for she had met a petty officer who had promised to marry her and take her away from Science for ever.

They had driven for several minutes before Quin spoke again.

‘Do you have her address?’

‘No, I don’t. She didn’t give it in her letter. That’s why I think she’s being someone in a book again. A sort of Victorian heroine going out into the snow.’ She glanced sideways at her passenger. He had been a famous scientist and would, if he survived, most probably be a hero with a medal, but he was still a man and the suspicion that she and Janet had harboured could not be voiced to him. ‘It’s not because she hasn’t gone with Heini that I’m worried. Obviously she didn’t love him and —’

‘Really? That was not my impression.’

God, don’t let it start again, he thought, looking out at the winter trees. There was no rage to call on nowadays; just a relentless sense of bereavement lying below his conscious thoughts as dark and heavy as stone.

‘I’m going to try and find her,’ said Pilly. She had switched on the headlights; they were turning into the road which led to the station. ‘The trouble is, my next leave is not for three months.’

‘How can you find her without an address?’

‘I think she’s in Cumberland — the postmark looked as though it might be Keswick.’ Pausing at a traffic light, she turned to look at him. ‘I’ve got the letter in my locker back at headquarters, if you had time to look — you’re good at deciphering things. And if it is Keswick, that’s not so far from Bowmont, is it? So if you were going north —’

‘But I’m not. I’ve got exactly forty-eight hours and it takes a whole day now to go north, as you know.’

Pilly sighed. Probably Dr Elke had been wrong. Probably she herself was mistaken. ‘If she was a dinosaur’s tooth you’d find her,’ she said. ‘And she isn’t; she’s Ruth.’

The car drew to a halt in front of the station. Quin reached for his duffel bag — and dropped it back on the seat.

‘All right, Pilly, you win. We’ll go and look at your envelope.’

But when Pilly hurried back to him in the hallway of the officers’ mess carrying the letter, she saw that Ruth’s cause was lost. Quin was staring at a telegram in his hand and his face was ashen.

‘Thank God we called in here,’ he said. ‘My aunt’s been taken ill. I’ll have to go to her at once.’

He handed her the message which had been waiting with the Vigilantes’ mail.

COME IMMEDIATELY WARD THREE NEWCASTLE GENERAL HOSPITAL URGENT SOMERVILLE.

There was no chance to sleep in the crowded, blacked-out train; nothing to eat or drink. There were only the dragging hours in which to recall, in unsought detail, the services his aunt had performed during her life and to realize the blow her death would deal him.

They reached Newcastle at ten in the morning and, still in his rumpled uniform, he snatched a few minutes to wash and shave in the station cloakroom before jumping into a taxi. He’d sent a cable before he left; giving his name at the hospital reception desk, he was directed to the first floor.

As he entered the ward, the Sister came towards him. ‘Ah yes, we’ve been expecting you. It’s not visiting time, but I understand the circumstances are exceptional. I’ll take you to your aunt.’

Steeling himself to face what awaited him, Quin followed her to the door of a small day room which she opened.

Aunt Frances was not ill and she was certainly not dead. As she saw him she rose and came towards him — and she was laughing. Not the reluctant smile she occasionally allowed herself at the foibles of mankind, but the full-bodied laughter of intense amusement.

‘Oh, thank goodness!’ She embraced him, but her shoulders still shook. ‘Only… don’t worry,’ she managed to say. ‘It’s just a few days and then it’ll disappear. He’ll lose it completely — isn’t that so, Sister?’

Sister agreed that it was.

‘Lose what?’ said Quin, completely bewildered.

‘The resemblance. The likeness. Oh dear, I wouldn’t have believed it! Go and see! She’s in the end bed on the left.’

Walking in a dream, Quin made his way up the ward. Girls were sitting up in bed, some talking, some knitting — but all watching him as he passed.

Then suddenly there was Ruth, her hair mantling her shoulders. Ruth as he remembered her… warm… feminine; somehow both triumphant and unsure.

But he didn’t go to her at once. At the foot of the bed, as at the foot of all the beds, was a cot. And inside it — lay Rear Admiral Basher Somerville.

The baby wasn’t like the Basher. It was the Basher — shrunk to size, a little more crumpled, but identical. The Beethovian nose, the bucolic, livid face, the double chin and pursed-up mouth.

Quin could not speak, only stare — and his son moved his ancient, wrinkled head, one eye opened — a fathomless, deep blue, lashless eye… the mouth twitched in a precursor of a smile.

And Quin was undone. In an instant, this being of whose existence he had been unaware five minutes earlier, claimed him, body and soul. At the same time, he knew that he could die now and it did not matter because the child was there and lived.

Only I must not hold him back, he thought. He is himself. I swear that I will let him go.

Then he looked up at Ruth, watching him in silence. But not her, he thought exultantly. Not her! I shall never relinquish her — and he moved, half-blind, to the head of the bed, and took her in his arms.

The Sister had said: ‘Half an hour, but no more, since you’re on leave.’ She had drawn the cold blue curtains round the bed, but the lazy December sun touched them with gold. Inside was Cleopatra’s barge, was Venus’ bower as Quin touched Ruth’s face, her hair.

‘I can’t believe it. I can’t believe you could have been so stupid. I just wanted to give you something lovely and priceless.’

‘I know… I was an idiot. I think I didn’t believe I should be happy when there was so much suffering in the world. And there was Verena. She told everyone that you were taking her to Africa.’

‘Ah, yes. An unpleasant woman. She’s going to marry Kenneth Easton and teach him how to pronounce Cholmondely, did you know?’

Ruth liked that. She liked it a lot. But Quin was still shaken by the risk he had taken when she came to him that night. ‘When I think that you went through all that alone.’

‘Well, actually I didn’t,’ said Ruth a trifle bitterly. ‘Not at the end. All I can say is that your aunt may have left you alone but she certainly didn’t leave me!’

And she described the moment when Aunt Frances had appeared in the doorway at Bowmont, apparently barring the way. ‘She said I couldn’t stay and I was desperate, but she meant I couldn’t stay in case we were cut off by the snow and the ambulance couldn’t get through. She just bundled me into the car and took me down to Mrs Bainbridge’s house in Newcastle and even when my parents came, she didn’t let me out of her sight. I think she was worried because of what happened to your mother.’

Quin took one of her hands, laced her fingers with his.

‘Thank God for Aunt Frances,’ he said lightly — but he was still troubled by his carelessness that night in Chelsea. Or was it carelessness? Would he have believed any other woman as he had believed Ruth? Hadn’t he wanted, at one level, to be committed as irrevocably as now he was?

But Ruth was asking a question, holding on to him rather hard in case it was unjustified.

‘Quin, when you give Bowmont to the Trust, do you think it might be possible to keep just one very small —’

‘When I do what?’ said Quin, thunderstruck.

‘Give Bowmont to the Trust. You see —’

‘Give it to the Trust? Are you mad? Ruth, you have seen that baby — you have seen the fists on him. Do you seriously think I’d dare to give away his home?’

Ruth seemed to find this funny. She found it very funny, and her remarks about the British upper classes were so uncomplimentary that Quin, slightly offended, prepared to seal her lips with a kiss. But when he’d cleared away her hair to obtain a better access, he found that her brow was furrowed by a new anxiety.

‘Quin,’ she said into his ear, ‘I seem to have become a mother rather quickly, but I want so much to be… you know… a proper loveress. The kind that wiggles a gentleman’s cigars to see that the tobacco is all right and knows about claret.’

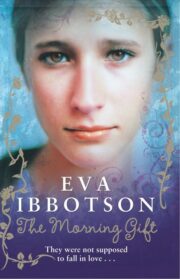

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.