The doorbell rang, shrill and insistent. Neither of the Bergers moved.

‘What are you going to do?’ asked the Professor — and the sudden helplessness of this proud man did touch her.

‘I’ll tell you what I’m going to do,’ she began.

A second ring… and now Fräulein Lutzenholler’s door could be heard opening, and her indignant footsteps as she made her way downstairs. The easing of laws against refugees at the onset of hostilities meant she was allowed to practise her profession and, incredible as it seemed, people came to her room and paid to have her listen. Answering the doorbell would annoy this exalted person very much.

She returned, as displeased as Leonie had anticipated, and with her was a red-faced man in some kind of uniform.

‘It’s the rodent officer,’ said Fräulein Lutzenholler — and as Leonie stared blankly at this man she had awaited with hope and passion for month after month: ‘He has come about the mice.’

‘Oh, yes… thank you…’ Leonie rose, tried to collect herself.

‘Please go where you will. They are everywhere. The kitchen is bad… and the back bedroom.’

‘That’s all right, ma’am. I’ll just get on with it. Looks like a sizable infestation you have here — I may have to take up some boards.’

He left the room and they could hear him moving about, tapping the walls, opening cupboards.

‘I’ll tell you what I’m going to do,’ said Leonie, turning back to her husband. ‘I’m going to take Ruth’s letter to the post office and make them tell me where it comes from and then I’m going to go there and find her. And when I have found her I’m going to bring her back here and look after her and after my grandchild. And if the father’s a chimney sweep I’m going to do it.’ She swallowed. ‘Even if he is a Nazi chimney sweep, because if Ruth gave herself to him it’s because she loved him and she is my blood and yours also, so you will please not —’

A knock at the door and the rodent officer reappeared.

‘I found this under the boards in the back room,’ he said — and deposited on the table a large, square biscuit tin covered in mouse droppings and adorned with a picture of the Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret Rose patting a corgi dog.

She had come by bus as far as Alnwick, but there were eight miles still to go before she reached Bowmont. She’d have walked it easily enough in the old days, but not now, and she spent some of her meagre stock of money on a taxi as far as the village. It would have made sense to be set down by the house itself, but she couldn’t face that. She didn’t want to sweep up as a claimant — it was sanctuary she sought at Bowmont, not her rights.

The driver was worried; she had a suitcase, the afternoon was grey and chill, but she reassured him.

‘I’ll be all right,’ she said. ‘I need some air.’

She certainly looked as though she needed something, thought the driver, turning his cab, watching the bundled figure in its shabby cape set off up the hill.

There was nobody about and that was a blessing; there might have been people who recognized her and till she knew her fate she wanted to speak to no one. And her fate depended on a ferocious old woman known for her sharp temper and her strict and old-fashioned views.

‘I hope you’re satisfied,’ she said bitterly, addressing her unborn child. She had fought a long battle, pitting her pride and independence against the creature’s blind, stubborn thrust towards what it considered to be its home, and she had lost. Now, trudging up the hill, she tried to face the consequences of rejection. Where would she go if she was turned away? It was growing dark, she could hardly go back to Penelope whose advice she had ignored… whom, in a sense, she had left in the lurch. She was mad, coming here like this at the eleventh hour.

‘Oh God, why did I listen?’ she thought, for the sense of dialogue between herself and the child had been with her from the start.

But she knew why. Even now, in the bitter cold of a raw December day with the storm clouds massing in the west and the light withdrawing itself in readiness for an endless winter night, she walked through a heart-stopping beauty. The wind-tossed trees, the tumble and thrust of the waves against the cliffs and Bowmont’s tower etched against a violet sky, brought a sudden mist of tears to her eyes — and that was not very sensible nor very practical. She had to find her way, not stumble, for she was not alone.

Yet memories, as she made her way up the last stretch of road, came unbidden to weaken her further. The incredible clarity of the stars; the dazzling silver of the morning sea the first time she had walked towards it; the enfolding, unexpected warmth and fragrance of the garden — and she thought that if she was sent away again she would not know how to bear it.

She was on the gravel drive now and still she had encountered no one. Then as she reached the steps and put down her suitcase, she knew with certainty that her quest would fail. Aunt Frances hated refugees, she hated foreigners; she belonged to a bygone age. There was no sanctuary here, no safety, no hope.

She could hear the clang of the bell echoing inside the house. Would Turton even announce her, seeing her state? She belonged at the back door or in one of those dark genre paintings of banished women staggering out into the night.

The bolt was drawn back slowly… so slowly that Ruth would have had time to turn away down the steps.

‘Yes? What is it?’

It was not Turton who stood there, not any of the servants. It was Aunt Frances herself, barring the way, showing no welcome, no inclination to move aside — not even when she recognized who it was that stood on her threshold.

‘What on earth are you doing here?’ she went on, horrified. ‘This is no place for you!’

Ruth drew breath, lifted her head. Not I, but thou… She must fight for her child. But the words she brought out were halting, inadequate; she was suddenly so exhausted that she could hardly stand.

‘Please… I beg you… Can I stay?’

‘Stay here! Stay here in your condition! Really, Ruth, I know all foreigners are mad but this goes beyond everything. Of course you can’t stay.’

‘There is an explanation… There is a reason.’

‘Explanations have nothing to do with it. You can’t stay here, absolutely and definitely not, and that’s the end of the matter.’

Ruth looked up at the gaunt fierce woman she had nevertheless hoped was her friend. As she pulled her cloak tighter, struck by a deathly cold, the first flakes of snow began to fall.

Chapter 29

It had been Pilly’s ambition, when she joined the WRNS, to be employed as a cook, but the third-class degree which made so little impression in academic circles secured her a status she did not really seek. She was deployed as a driver and by the end of November was carrying signals to and from the docks and senior naval officers about their business.

But the officer she had been asked to collect from the destroyer Vigilantes at an outlying berth some ten miles from the base was a mere sublieutenant and it was better not to ask why he rated a car or why the ship, supposedly on Atlantic convoys, was being refitted in this obscure and inconveniently sited dock on the South Coast. There were a lot of things one did not ask this first winter of the war.

It was a raw December afternoon; the quay was deserted except for the two sailors guarding the barrier, but Pilly, standing beside her car, waited contentedly. Her instructions were clear; her passenger would come.

But when he did come, a lone figure carrying a duffel bag, and she saluted, the result was unexpected.

‘Good God, Pilly!’ Quin peered, moved closer in the dusk. ‘It is you, isn’t it?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Well, well, this is amazing!’ He threw his bag into the back and climbed into the front seat. ‘I had no idea you were in the same outfit. How do you like it?’

‘I absolutely love it!’

Quin smiled at the enthusiasm in her voice and at the change in the nervous girl who had peered so sadly at her specimens. Pilly was slimmer, the uniform suited her, and as they turned inland, he saw that she handled the big car with confidence and skill.

‘My instructions are to take you to the station,’ she said, ‘but it wouldn’t take a minute to call in at the mess if you wanted to pick up your mail?’

‘No, thanks.’

The mail was of no interest to him now. He had put a moratorium on his past life. In the forty-eight hours before his next assignment, he was going down to a pub in Dorset to walk and eat and sleep. Mostly to sleep.

‘Janet’s in the ATS,’ Pilly said, for she knew she must ask him nothing personal, ‘though she’s getting married soon, and Huw is in the army. And Sam’s going to join the RAF.’

Quin turned his head sharply. ‘He could have got deferment with a Science degree. I told him.’

‘Yes — but he wanted to be part of it. He really hates the Nazis and not just because he was so fond of Ruth.’

She changed down and they began to climb up the slope of the Downs. Well, it was inevitable that the girl who had followed Ruth like a shadow, should mention her name. Impossible, now, not to proceed.

‘Have you heard from Ruth?’

‘Yes, I have. I heard two weeks ago.’

‘And how does she like America?’

No answer. They had reached the top of the hill and she turned left between trees. Thinking she might need to concentrate on the dark stretch of road, he waited, but when she still did not answer, he repeated his question.

Pilly made up her mind. ‘She is not in America,’ she said.

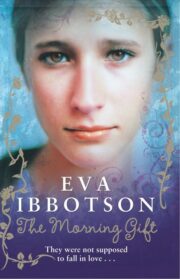

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.