Of Ruth he saw relatively little, for in one of those wooden huts so beloved of Austrian musicians, her Cousin Heini practised the piano and she was busy carrying jugs of milk or plates of biscuits to and fro. Once he found her sitting by the shore with a somewhat surprising collection of books. Krafft-Ebing’s Sexual Pathology, Little Women and a cowboy story with a lurid cover called Jake’s Last Stand.

It was the Krafft-Ebing she was perusing with a furrowed brow.

‘Goodness!’ he said. ‘Are you allowed to read that?’

She nodded. ‘I’m allowed to read everything,’ she said. ‘Only I have to eat everything too, even semolina.’

But on the night before he had to leave, Miss Kenmore could no longer be gainsaid and Quin was informed that Ruth would recite Keats’ ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ for him after supper.

‘She has it entirely by heart, Dr Somerville,’ she said — and Quin, repressing a sigh, joined the family in the drawing room with its long windows open to the lake.

Ruth’s fair hair had been brushed out; she wore a velvet ribbon — clearly the occasion was important — yet at first Quin was compelled to look at the floor and school his expression, for she spoke the famous lines in the unmistakable accent of Aberdeen.

Only when she came to the penultimate verse, to the part of the poem that belonged personally to her, for it was about her namesake, did he lift his head, caught by something in her voice.

Perhaps the self-same song that found a path

Through the sad heart of Ruth, when, sick for home,

She stood in tears among the alien corn…

Hackneyed lines, lines he had grown weary of at school, they still had power to stir him.

Yet no one there, not one of the people who loved her, not Quin, not Ruth herself, enjoying the poem’s sadness, were touched by a single glimmer of premonition. No hairs lifted on the nape of any necks; no ghosts walked over the quiet waters of the lake. That this protected, much-loved child should ever have to leave her native land, was unimaginable.

The next day, Quin left for England. The family all came to see him off and begged him to come back soon — but it was eight years before he returned to Vienna and then he came to a different city and a different world.

Chapter 1

On the day that Hitler marched into Vienna, Professor Somerville was leading his not noticeably grateful expedition down a defile so narrow that overshadowing precipices blocked out all but a strip of the clear blue sky of Central Asia.

‘You can’t possibly get the animals down this way,’ a Belgian geologist he had been compelled to take along had complained.

But Quin had just said vaguely that he thought it might be all right, by which he meant that if everyone nearly killed themselves and did exactly what he told them, there was a chance — and now, sure enough, the chasm widened, they passed the first trees growing wherever roots could take hold, and made their way through forests of pine and cedar to reach, at last, the bottom of the valley.

‘We’ll camp here,’ said Quin, pointing to a place where the untroubled river, idling past, dragged at the overhanging willows, and drifts of orchids and asphodels studded the grass.

Later, when the mules were grazing and the smoke from the fire curled upwards in the still air, he leant back against a tree and took out the battered pipe which many women had tried to replace. He was thirty years old now, lines were etched into the crumpled-looking forehead and the sides of the mouth, and the dark eyes could look hard, but at this moment he was entirely happy. For he had been right. In spite of the gloomy prognostications of the Belgian whose spectacles had been stepped on by a yak; in spite of the assurances of his porters that it was impossible to reach the remoter valleys of the Siwalik Range in the spring, he had found as rich a collection of Miocene fossils as anyone could hope for. Wrapped now in woodwool and canvas, more valuable than any golden treasure from a tomb, was the unmistakable evidence of Ramapithecus, one of the earliest ancestors of man.

There were three weeks of travelling still along the river valley before they could load their specimens onto lorries for the drive down to Simla, but the problems now would be social: the drinking of terrible tea with the villagers, bedbugs, hospitality…

A lammergeier hung like a nail in the sky. The bells of browsing cattle came from a distant meadow, and the wail of a flute.

Quin closed his eyes.

News of the outside world when it came at last was brought by an Indian army officer in the rest house above Simla and was delivered in the order of importance. Oxford had won the Boat Race, an outsider named Battleship had romped home at Aintree.

‘Oh, and Hitler’s annexed Austria. Marched into Vienna without a shot being fired.’

‘Will you still go?’ asked Milner, his research assistant and a trusted friend.

‘I don’t know.’

‘I suppose it’s a terrific honour. I mean, they don’t give away degrees in a place like that.’

Quin shrugged. It was not the first honorary degree he had been awarded. Persuaded three years ago to take up a professorship in London, he still managed to pursue his investigations in the more exotic corners of the world, and he had been lucky with his finds.

‘Berger arranged it. He’s Dean of the Science Faculty now. If it wasn’t for him I doubt if I’d go; I’ve no desire to go anywhere near the Nazis. But I owe him a lot and his family were very good to me. I stayed with them one summer.’

He smiled, remembering the excitable, affectionate Bergers, the massive meals in the Viennese apartment, and the wooden house on the Grundlsee. There’d been an accident-prone anthropologist whose monograph on the Mi-Mi had fallen out of a rowing boat, and a pig-tailed little girl with a biblical name he couldn’t now recall. Rachel…? Hannah…?

‘I’ll go,’ he decided. ‘If I jump ship at Izmir I can connect with the Orient Express. It won’t delay me more than a couple of days. I know I can trust you to see the stuff through the customs, but if there’s any trouble I’ll sort it out when I come.’

The pigeons were still there, wheeling as if to music in this absurdly music-minded city; the cobbles, the spire of St Stephan’s glimpsed continually from the narrow streets as his taxi took him from the station. The smell of vanilla too, as he pulled down the windows, and the lilacs and laburnums in the park.

But the swastika banners now hung from the windows, relics of the city’s welcome to the Führer, groups of soldiers with the insignia of the SS stood together on street corners — and when the taxi turned into a narrow lane, he saw the hideous daubings on the doors of Jewish shops, the broken windows.

In Sacher’s Hotel he found that his booking had been honoured. The welcome was friendly, Kaiser Franz Joseph in his mutton chop whiskers still hung in the foyer, not yet replaced by the Führer’s banal face. But in the bar three German officers with their peroxided girlfriends were talking loudly in Berlin accents. Even if there had been time to have a drink, Quin would not have joined them. In fact there was no time at all for the unthinkable had happened and the fabled Orient Express had developed engine trouble. Changing quickly into a dark suit, he hurried to the university. Berger’s secretary had written to him before he left England, explaining that robes would be hired for him, and all degree ceremonies were much the same. It was only necessary to follow the person in front in the manner of penguins.

All the same, it was even later than he had realized. Groups of men in scarlet and gold, in black and purple, with hoods bound in ermine or tasselled caps, stood on the steps; streams of proud relatives in their best clothes moved through the imposing doors.

‘Ah, Professor Somerville, you are expected, everything is ready.’ The Registrar’s secretary greeted him with relief. ‘I’ll take you straight to the robing room. The Dean was hoping to welcome you before the ceremony, but he’s already in the hall so he’ll meet you at the reception.’

‘I’m looking forward to seeing him.’

Quin’s gown of scarlet silk, lined with palatine purple, was laid out on a table beside a card bearing his name. The velvet hat was too big, but he pushed it onto the back of his head and went out to join the other candidates waiting in the anteroom.

The organist launched into a Bach passacaglia, and between a fat lady professor from the Argentine and what seemed to be the oldest entomologist in the world, Quin marched down the aisle of the Great Hall towards the Chancellor’s throne.

As he’d expected in this city, where even the cab horses were caparisoned, the ceremony proceeded with the maximum of pomp. Men rose, doffed their caps, bowed to each other, sat down again. The organ pealed. Long-dead alumni in golden frames stared down from the wall.

Seated to the right of the dais, Quin, looking for Berger in the row of academics opposite, was impeded by the hat of the lady professor from the Argentine who seemed to be wearing an outsize academic soup tureen.

One by one, the graduates to be honoured were called out to have their achievements proclaimed in Latin, to be hit on the shoulder by a silver sausage containing the charter bestowed on the university by the Emperor Maximilian, and receive a parchment scroll. Quin, helping the entomologist from his chair, wondered whether the old gentleman would survive being hit by anything at all, but he did. The fat lady professor went next. His view now unimpeded, Quin searched the gaudily robed row of senior university members but could see no sign of Berger. It was eight years since they had met, but surely he would recognize that wise, dark face?

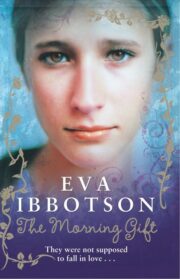

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.