‘Yes. The Adagio in B Minor.’

He finished playing and looked at her and found her entirely pleasing. He liked her fair hair in its old-fashioned heavy plait, her snub nose, the crisp white blouse and pleated pinafore. Above all, he liked the admiration reflected in her eyes.

‘I musn’t disturb you,’ she said.

He shook his head. ‘I don’t mind you being here if you’re quiet,’ he said.

And then he told her about Mozart’s starling.

‘Mozart had a starling,’ Heini said. ‘He kept it in a cage in the room where he worked and he didn’t mind it singing. In fact he liked it to be there and he used its song in the Finale of the G Major Piano Concerto. Did you know that?’

‘No, I didn’t.’

He watched the thick plait of hair swing to and fro as she shook her head.

Then: ‘You can be my starling,’ Heini said.

She nodded. It was an honour he was conferring; a great gift — she understood that at once.

‘I would like that,’ said Ruth.

And from then on, whenever she could, she settled quietly in the room where he practised, sometimes with her homework or a book, mostly just listening. She turned the pages for him when he played from a score, her small, square-tipped fingers touching the page as lightly as a moth. She waited for him after lessons, she took his tattered Beethoven sonatas to the bookbinder to be rebound.

‘She has become a handmaiden,’ said Leonie, not entirely pleased.

But Ruth did not neglect her school work or her friends, somehow she found time for everything.

‘I want to live like music sounds,’ she had said once, coming out of a concert at the Musikverein.

Serving Heini, loving him, she drew closer to this idea.

So Heini stayed in Vienna and that summer, preceded by a hired piano, he joined the Bergers on the Grundlsee.

And that summer, too, the summer of 1930, a young Englishman named Quinton Somerville came to work with the Professor.

Quin was twenty-three years old at the time of his visit, but he had already spent eighteen months in Tübingen working under the famous palaeontologist Freiherr von Huene, and arrived in Vienna not only with a thorough knowledge of German, but with a formidable reputation for so young a man. While still at Cambridge, Quin had managed to get himself on to an expedition to the giant reptile beds of Tendaguru in Tanganyika. The following year he travelled to the Cape where the skull of Australopithecus africanus had turned up in a lime quarry, setting off a raging controversy about the origin of man, and came under the influence of the brilliant and eccentric Robert Broom who hunted fossils in the nude and fostered Quin’s interest in the hominids. To avoid guesswork and flamboyance when Missing Link expeditions were fighting each other for the ‘dragon bones’ of China, and scientists came to blows about the authenticity of Piltdown Man, was difficult, but Quin’s doctoral thesis on the mammalian bone accumulations of the Olduvai Gorge was both erudite and sober.

Professor Berger met him at a conference and invited him to Vienna to give the Annual Lecture to the Palaeontological Society, suggesting he might stay on for a few weeks to help edit a new symposium of Vertebrate Zoology.

Quin came; the lecture was a success. He had just returned from Kenya and spoke with unashamed enthusiasm about the excitement of the excavations and the beauty of the land. It had been his intention to book into a hotel, but the Professor wouldn’t hear of it.

‘Of course you will stay with us,’ he said, and took him to the Felsengasse where his family found themselves surprised. For it was well known that Englishmen, especially those who explored things and hung on the ends of ropes, were tall and fair with piercing blue eyes and braying, confident voices which disposed of natives and underlings. Or at best, if very well bred, they looked bleached and chiselled, like crusaders on a tomb, with long, stately noses and lean hands folded over their swords.

In all these matters, Quin was a disappointment. His face looked as though it needed ironing; the high forehead crumpled at a moment’s notice into alarming furrows, his nose looked slightly broken, and the amused, enquiring eyes were a deep, almost a Mediterranean brown. Only the shapely hands with which he filled, poked at and tapped (but seldom lit) an ancient pipe, would have passed muster on a tomb.

‘But his shoes are handmade,’ declared Miss Ken-more, Ruth’s Scottish governess. ‘So he is definitely upper class.’

Leonie was inclined to believe this on account of the taxis. Quin, accompanying them to the opera or the theatre, had only to raise the fingers of one hand as they emerged for a taxi to perform a U-turn in the Ringstrasse and come to a halt in front of him.

‘And there is the shooting,’ said Ruth, for the Englishman, at the funfair in the Prater, had won a cut-glass bowl, a goldfish and an outsize blue rabbit and been requested by the irate owner of the booth to take his custom elsewhere. And what could that mean except a background of jolly shooting parties on breezy moors, disposing of pheasants, partridges and grouse?

The reality was different. Quin’s mother died when he was born; his father, attached to the Embassy in Switzerland, volunteered in 1916 and was killed on the Somme. Sent back to the family home in Northumberland, Quin found himself in a house where everyone was old. An irascible, domineering grandfather — the terrifying ‘Basher’ Somerville — presided over Quin’s first years at Bowmont and the spinster aunt who came to take over after his death hardly seemed younger. But if there was no one to show the orphaned boy affection, he was given something he knew how to value: his freedom.

‘Let the boy run wild,’ the family doctor sensibly advised when Quin, soon after his arrival, developed a prolonged and only partly explained fever. ‘There’s time for school later; he’s bright enough.’

So Quin had his reprieve from the monotony of British boarding schools and furnished for himself a secret and entirely satisfactory world. Most children, especially only ones, have an invisible playmate who accompanies them through the day. Quin’s, from the age of eight, was not an imaginary brother or understanding boy of his own age; it was a dinosaur. The creature — a brontosaurus whom he called Harry — stretched sixty feet; his head, when he put it through the nursery window, filled the room and its heart-warming smile was without menace for he ate only the bamboo in the shrubbery or the moist plants in the coppice which edged the lawn.

An article in The Boy’s Own Paper had introduced him to Harry; Conan Doyle’s The Lost World plunged him deeper into the fabled world of pre-history. He became the leader of the dinosaurs, a Mowgli of the Jurassic swamps who learnt to tame even the ghastly tyrannosaurus rex on whose back he rode.

‘I must say, you don’t have to spend time amusing him,’ said his nurse, not realizing that nothing could compete with the dramas Quin enacted in his head. From the dinosaurs, the boy went backwards and forwards in time. He read of the geological layers of the earth, of lobe-finned fishes and the mammals of the Pleistocene. By the time he was eleven, he was risking his life almost daily, scrambling down cliffs and quarries, searching for fossils embedded in the rock, and had started a collection in the old stables grandly labelled ‘The Somerville Museum of Natural History’. As he grew older and Harry became dimmer in his mind, the museum was expanded to take in the marine specimens he found everywhere. For Quin’s home looked out over the North Sea to the curving, sand-fringed sweep of Bowmont Bay whose rock pools were his nursery; the creatures inside them more interesting than any toy.

Quin would have been surprised if anyone had told him he was ‘doing science’ or becoming educated, but later, at Cambridge, he was amused by the solemnity with which they taught facts which he had learnt before his eleventh year, and the elaborate preparations for field trips to places he had clambered up and down in gym shoes.

He got a First in the Natural History Tripos with embarrassing ease, but his unfettered childhood made him reluctant to accept a permanent academic post. Financially independent since his eighteenth birthday, he had managed to spend the greater part of his time on expeditions to inaccessible parts of the world, yet now he fell in love with Vienna.

Not with the Vienna of operettas and cream cakes, though he took both politely from the hands of his hostess, but with the austere, arcaded courts of the university with its busts of old alumni resounding like a great roll call of the achievements of science. Doppler was there in stone, and Semmelweis who rid women of puerperal fever, and Billroth, the surgeon who befriended Brahms. In the library of the Hofburg, Quin spun the great gold-mounted globe which the Emperor Ferdinand had consulted to send his explorers forth. And in the Natural History Museum, he found a tiny, ugly, potbellied figurine, the Venus of Willendorf, priceless and guarded, made by man at the time when mammoths and sabre-toothed tigers still roamed the land.

When the university term ended, the Bergers begged him to join them on the Grundlsee.

‘It’s so beautiful,’ said Ruth. ‘The rain and the salamanders — and if you lie on your stomach on the landing stage you can see hundreds of little fishes between the boards like in a frame.’

He was due back in Cambridge, but he came and proved an excellent bilberry picker, an enthusiastic oarsman and a man able to shriek ‘Wunderbar!’ with the best of them. If they enjoyed his company, he, in turn, took back treasured memories of Austrian country life: Tante Hilda in striped bathing bloomers performing a violent breaststroke without moving from the spot… The Professor’s ancient mother running her wheelchair at a trespassing goat… And Klaus Biberstein, the second violin of the Ziller quartet, who loved Leonie but had a weak digestion, creeping out at midnight to feed his secreted Knödel to the fish.

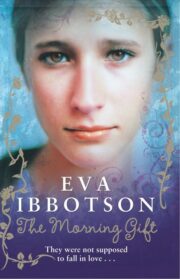

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.