“Yes, it could,” said Mr. Fitzhugh, snagging his sister before she could get past him. “There’s no need. What nodcock would go about sticking messages inside a pudding? They would get all goopy that way.”

“What nodcock would put a message on a pudding?” Sally countered. “The French are capable of anything.”

“Including, but not limited to, flaky pastries,” murmured Arabella.

Both Fitzhughs looked at her with identical expressions of confusion.

“What?” said Sally, as her brother chimed in with, “I say, what was that?”

“Nothing,” said Arabella hastily. “Never mind.” Once they got on to pastries, there would be no going back. The girls would probably dismember every brioche in the place, looking for freakishly small spies.

“I mean it, Sal,” said Mr. Fitzhugh, looking severely at his sister, or as severely as his genial features would allow. “No running about sneaking out of the school after puddings. I’ll go to Farley Castle for you, but only on condition that you stay here. Inside. Where you’re meant to be.”

“And I will be here to make sure you abide by that,” said Arabella. She had spoken quietly, but they all turned to look at her. Now seemed as good a time as any to tell them. She took a deep breath. “I shall be starting here on Monday as a junior instructress.”

“Will you? How splendid!”

“Don’t worry, we’ll show you exactly how to go about! You won’t have to fret about a thing!”

“Are you sure you know what you’re getting yourself into?” muttered Mr. Fitzhugh.

“No,” admitted Arabella. There was no point in pretending, was there? Funny how easy it could be to talk to a man once he had seen you sprawled on the ground, not once, but twice. “But I am committed now. I told Miss Climpson that I would be ready to begin on Monday.”

Mr. Fitzhugh looked at her with undisguised pity in his eyes. “Wouldn’t want to be in your shoes. I say. You don’t start until Monday?”

“Ye-es.” Monday did generally mean Monday. It wasn’t exactly Arabella’s favorite day of the week, but it was what it was. “Why do you ask?”

“I say,” Mr. Fitzhugh said hesitantly. “Would you consider — that is, if one were to — what I mean is, this jaunt to Farley Castle. Might I prevail on you to bear me company? That is, if you fancy the drive.”

As a pleasure jaunt, the prospect left something to be desired. It was bitterly cold, it would mean hours in an open carriage and then more hours in an open ruin of a castle. If the weather were well inclined, it might simply be frigid cold. Being England, it would probably rain as well. There was nothing like freezing rain to enhance a long drive in an open conveyance with a man who had been nicknamed for a vegetable.

Jane had said that Aunt Osborne was in Bath, part of a party come up from London for an assembly and a frost fair. It didn’t seem likely that there could be more than one of the latter. It wasn’t the most popular form of entertainment, for obvious reasons. If there was a frost fair, Aunt Osborne was sure to be in attendance.

Aunt Osborne and Captain Musgrave.

“Are you sure you wouldn’t mind having me along?” Arabella heard herself saying. “I wouldn’t want to be a bother.”

Mr. Fitzhugh shook his head emphatically. “You don’t know the first thing about being a bother. Takes years of practice to be a proper bother. Just ask Sal.”

“I heard that!” chimed in Sally, and turned back to her friends.

“See what I mean?” said Mr. Fitzhugh darkly.

“I don’t... ,” began Arabella.

Mr. Fitzhugh planted the palms of his hands on his knees and leaned forward beseechingly. “You can bear witness to Sal that I really did go to Farley Castle. It might stop her sneaking out in the middle of the night. I hope. Besides, we might find out who set the pudding thief on you.”

“Isn’t there one slight problem with that?” said Arabella. She hated to ruin their excitement, but there was one fatal flaw with the plan. “The message never reached its intended recipient. And whoever sent it knows it.” She should know. Her posterior still ached from the aftermath.

“Details, details,” said Sally airily. “Did you see what that message said? Most urgent. If it really is most urgent, she’ll find another way to get the message out. I know I would.”

Turnip exchanged an alarmed glance with Arabella. “Can’t persuade you to come along with me anyway, can I? Fascinating place, Farley Castle. Goes back to the Normans, dontcha know. It’s a pleasant drive, when the weather is nice.”

In the space of a few days, Farley Castle would be as distant as the moon as far as she was concerned. These pleasant blue and white walled rooms would comprise the whole of her existence, save for those half days when she would be set free to visit with the Austens four houses away or to make the vast journey across the town to see her own family in Westgate Buildings. There would be none of even the milder forms of entertainments, no supper parties, no concerts, no turns about the Pump Room.

There would certainly be no carriage rides with handsome young men.

It didn’t matter that he invited her only because he didn’t want to drive alone, or because it had been from her hand that the pudding had been plucked, or because he hoped that her presence as witness would satisfy his volatile little sister. It would be one last adventure before the walls of the schoolroom closed about her.

Arabella looked at Mr. Fitzhugh, who was extolling the pleasures of frost fairs, the mulled wine and crisp air, the refreshments and the entertainments. He was, she thought appraisingly, undeniably a fine figure of a man. He was also, despite his nickname, accounted a great catch on the marriage market. Arabella knew it was silly, but there was something very satisfying about the idea of walking into Farley Castle on Mr. Fitzhugh’s arm. She might know that their seeming intimacy was a sham, but other people wouldn’t.

What would Captain Musgrave think when she strolled in on the arm of Reginald Fitzhugh?

“All right,” said Arabella.

“Never know what we might find there! We might — all right?”

“All right,” Arabella repeated, smiling across at him. Something about Mr. Fitzhugh’s open enthusiasm was infectious. Even if he was a Turnip.

“Splendid!” exclaimed Mr. Fitzhugh, and he sounded as though he really thought it was. “Should be an amusing excursion, even if it is all a mad duck romp.”

“You mean a wild goose chase?”

“That too,” said Mr. Fitzhugh airily. “Can’t get away from the fowl, it seems.”

Sally twisted in her chair, pearl earbobs swinging. “Do not mention the chickens!”

“What happened?” demanded Jane in an undertone. “Did you get the position?”

It was the first chance they had to speak privately since Arabella had arrived, breathless, only moments ahead of the rest of her family.

After supper, the entire party had adjourned upstairs to the drawing room. In the chairs nearest the fire, Papa and Mr. Austen had their heads together over a knotty piece of Virgil. It saddened Arabella to see how old her father looked, how gray and drawn. He had been Mr. Austen’s pupil once, but the poor health that had plagued him since her mother’s death made him look more his old tutor’s contemporary than his junior. Cassandra had taken on the managing of Margaret for the evening, and was speaking to her determinedly of bonnets and trimmings. Olivia sprawled by the fire at their father’s feet, her nose buried in one of Mr. Austen’s books, while Mrs. Austen busied herself with the tea tray, handing the cups to Lavinia to hand around, an act of extreme faith, given Lavinia’s habit of dropping, knocking over, or bumping into things with limbs recently grown too long to manage properly.

Through the long windows that looked out onto the Sydney Gardens, Arabella could just make out the side of Miss Climpson’s seminary. Or she could if she leaned and squinted. Odd to think that it would be her home soon, that she would look out onto these very same gardens.

Although, as junior faculty, it was more likely that she would look out onto the service area, up several steep flights of stairs.

“Well?” Jane demanded. “Are you to keep me in suspense all evening? Will you be shaping the minds of the young for years to come?”

“You needn’t sound like you hope the answer will be no!”

Jane shook her needlework out on her lap. “I didn’t say that.”

“No, but it was heavily implied.”

Jane rolled her eyes. “Heaven forfend that I should stand accused of imputation. So you did get it, then?”

“Imputation and assumption! But yes. I did.”

“Ought I to wish you happy?”

“I’m not marrying the school, only working there. Besides,” Arabella added hastily, before Jane could say anything too cutting, “I had the oddest adventure along the way. Do you know Mr. Fitzhugh?”

“The one they call Turnip? Possessed of every worldly endowment except intellect?”

“Ouch,” said Arabella. “He’s not so bad as all that. He’s very sweet, really.”

Jane furrowed her brow at her. “You’re not...”

“No! No. He’s not a Mr. Bigg-Wither.”

Jane pulled a wry face at the reference to her one-day betrothal. “You mean he doesn’t stutter?”

“I mean he hasn’t offered for me. His sister is at the school. That’s all. Well, not quite all.” How did one go about explaining about purloined Christmas puddings? “It’s a very long story,” she finished lamely.

“Those are generally the best kind,” said Jane. “Shall I have it in three volumes with appropriate moral interpolations between the chapters?”

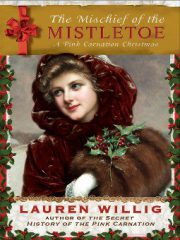

"The Mischief of the Mistletoe" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe" друзьям в соцсетях.