As the set disintegrated, some going off to find other partners, others heading for the refreshment tables, Arabella self-consciously fanned her flushed face. “It is rather warm in here, isn’t it?”

Warm didn’t even begin to describe it.

Turnip seized on the excuse. “Shall we take the air? It will be cooler outside on the balcony.”

If he had had a club on him, he would have banged her over the head and borne her off to his cave. Being a supposedly civilized nineteenth-century gentleman, the best he could do was a balcony.

In Norfolk. In January. Not exactly the most romantic gesture in the world, shivering in the frigid cold. Perhaps that was why Shakespeare had set so many of his comedies in warm climates, and only the tragedies in cold ones. Wouldn’t be much of a romance with Beatrice and Benedick both succumbing to pneumonia before the end of the second act.

Arabella looked to the corner where her aunt sat, gossiping with the Dowager Lady Pinchingdale. “My aunt doesn’t seem to need her left rib yet.”

“If she does, her husband can get it,” said Turnip, tucking Arabella’s hand beneath his arm before she could change her mind. That hadn’t been precisely a yes, but Turnip felt secure in taking it as one. “That’s what they’re for. Husbands, I mean, not ribs. Jolly useful things, husbands,” he added. It was never too early to set the groundwork. “Or so I hear.”

As they walked through the French doors onto the balcony, Arabella surveyed the breadth of the veranda, a curious expression on her face. “So this is what a balcony looks like by night.”

“Much as it does by day. Doesn’t move about much, you know. Attached to the house and all that.”

“I always used to be” — she hunched her shoulders selfdeprecatingly — “a little bit envious of those women who slipped off to balconies during a ball. I know one is supposed to disapprove, but...”

She looked up at him and shrugged, acknowledging the inevitability of human frailty.

Turnip was feeling pretty bally frail just about now. The fall of man had never made more sense than it did now. His only regret was that he had wasted so much time. There had been so many ballrooms and so many balconies that they could have shared.

“Well, here you are! Nothing like making up for lost time.”

Arabella wrinkled her nose at him. “There’s no need to mock.”

“Wouldn’t think of it,” Turnip assured her, scanning the balcony for a properly secluded spot, someplace near enough to the door for warmth, but far enough away for privacy. “Not a mock on me. Entirely mock-free.”

“Just because you’ve been out on dozens of balconies...”

“Yes, but never one so nice as this. Shan’t look at another balcony ever again.” Turnip pointed to a nice little area about three feet over, near enough to the door to still be considered respectable, but nicely out of view. “I say, that’s a charming patch of balustrade over there. Let’s go lean on it.”

“Oh,” said Arabella, her eyes bright with amusement, her cheeks flushed with cold and exertion, “is that what one does on balconies?”

“That and play tiddlywinks,” said Turnip giddily, putting his hand on the small of her back to guide her. Her hair brushed his cheek as she turned her head, and he smelled soap and lilac.

“I’ll warn you,” said Arabella, looking up at him. “I’m a fierce tiddlywink player.”

Turnip touched a hand to her cheek, admiring the messy wisps of her hair, the reddening tip of her nose, the remains of a dust smudge on her chin.

“I wouldn’t expect anything less,” he said tenderly.

She looked at him with wide, uncertain eyes, knowing as well as he that they weren’t talking about tiddlywinks anymore. But she didn’t say anything. And she didn’t pull away. Beyond them, the parkland stretched out in all its winter barrenness, but Turnip could have sworn he smelled flowers blooming.

Arabella’s lashes fluttered down to cover her eyes.

And abruptly popped up again as the balcony door banged open.

Turnip hastily moved to shield her with his body; he wasn’t even sure why or from what, it was just an automatic reflex.

A girl in a white-and-silver dress came tumbling through the door, her brilliant red hair caught high above her head, threaded with matching silver ribbons, her every move a challenge as she gestured back over her shoulder at the man following close behind her.

“Too cold for you, Freddy?” she demanded, her voice husky. Turnip could feel Arabella stiffen beside him at the sound of it.

“Is that a challenge?” Lord Frederick Staines asked, sauntering through the ballroom doors. He stood silhouetted in the light from the ballroom, hands in his pockets, the picture of aristocratic boredom.

Already at the bottom of the steps, Penelope tilted her head up at him. Neither of them seemed to have noticed the couple in the shadows on the side of the balcony. Or if they had, they didn’t care. “It is if you choose to take it as such.”

Lord Frederick laughed, a low, arrogant sound that made Turnip think of the horns blown to signal the beginning of the hunt. He bounded down the steps, catching Penelope around the waist. “I’ll take whatever I like.”

She twisted away, lithe in the moonlight, part hunted, part huntress. “We’ll see about that.”

They disappeared into the shadows, Penelope’s slippers soundless, Lord Frederick’s booted feet crunching on the gravel.

“Not good,” Turnip said. “Not good a’tall.”

“No.” He looked down to find Arabella watching him, all the humor that had animated her face a moment ago gone. She looked weary and more than a little bit unhappy. “I’m sorry,” she said, and the words seemed to cost her an effort.

“So am I,” agreed Turnip. Not that he should talk, having inveigled Arabella out onto the balcony, but there was a difference. He knew his intentions were honorable. Staines wouldn’t know honorable if it bit him in the backside. Penelope might be a bit of a wild thing, but she was a good soul at heart. She deserved better. “Staines is a rotter.”

Stepping away from him, Arabella placed both hands on the flat surface of the balustrade, leaning her weight on her palms as she gazed out over the thickly planted shrubbery. “Perhaps if you said something?”

“Doubt old Pen would thank me for going jumping over the balcony and disturbing her fun.”

For that matter, he wasn’t entirely thrilled with old Pen for having disrupted his. One minute they had been laughing with each other, a whisper away from a kiss, and now Arabella was as distant as the moon.

Turnip didn’t understand it. He didn’t understand it at all. Did she want him to go rescue Penelope? Was that it?

Arabella appeared to have developed a deep interest in the urn on the side of the balustrade. Not that it wasn’t a perfectly nice urn, but it had the unfortunate effect of turning her face well out of his view.

“Did you ever think to declare yourself?” she asked the urn.

“Declare? Declare what?”

Arabella waved her hands helplessly. “Your feelings. For her.”

Feelings?

Turnip looked sharply at Arabella who was very pointedly not looking at him. “You didn’t think that Penelope — ? That I — ?” It was too absurd to articulate. “By Gad, that’s a good one.”

“I don’t see how it’s funny,” said Arabella stiffly. “Everyone keeps saying you mean to marry her.”

“Pen is — well, she’s a chum.”

More than a chum if one counted those interludes on balconies, but Turnip deemed it wiser not to go into that. Penelope took something of a male approach to things like balconies, but Turnip didn’t think Arabella would quite understand that.

“We’ve known each other since I was in dresses. But marry her?” Turnip shuddered dramatically. “She’d have me for breakfast.”

“With or without raspberry jam?” Arabella asked suspiciously.

“Without,” Turnip said with authority. “Pen is more a marmalade sort of girl. More tart than sweet, don’t you know.”

“No, I wouldn’t know,” said Arabella crankily. “But I do know that it’s very cold out here.”

She pushed away from the balustrade, making as though to go to the door, but Turnip moved to block her. “You’re jealous, aren’t you?”

She blinked at him. “I beg your pardon?”

Hmm. Maybe he oughtn’t to have said that aloud.

“She’s not the flavor of jam I want,” he said hastily. “Never has been. Didn’t mean to give anyone that idea, least of all you.”

Arabella hastily shook her head, not looking at him. “You don’t need to explain yourself to me. Really.”

Turnip took her chin in his hand, raising her face to his. “Yes, I do. Wouldn’t be able to live with myself if I didn’t.” More important, he wouldn’t be able to live with her. “Your good opinion matters to me. It matters a lot.”

He wasn’t doing a very good job of this, was he? At least she had stopped trying to wiggle past him.

She bit her lip, as though unsure what to say. “Thank you. I value your good opinion too.”

They sounded like a couple of Oxford dons exchanging commendations. Bother, bother, bother. Next they would be shaking hands and saying things like “value and esteem,” which were about as passionate as a glass of warm milk.

Turnip planted his hands on the balustrade on either side of her, effectively boxing her in. “What I’m trying to say is — ” What was he trying to say? “You don’t have a handkerchief, do you?” he blurted out, playing for time.

Now he understood why chaps generally liked to have a ring about them when they proposed. Whipping it out bought a chap time to figure out what he was trying to say. The shinier the ring, the longer the reprieve.

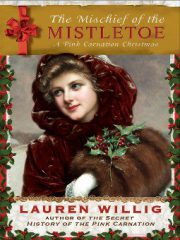

"The Mischief of the Mistletoe" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe" друзьям в соцсетях.