Right now, he was not so much exuberant as anxious, drumming his fingers against the mantelpiece, pacing in short explosive bursts between Arabella’s chair and the fire, whipping around every few minutes to peer at her, as though he were afraid that she might disappear again.

He caught her catching him staring at her and gave her a lopsided smile that didn’t hide the worry in his eyes.

She smiled back ruefully.

It didn’t do to read too much into his concern. He would have done the same for Lady Pinchingdale or Jane or a stray cat that sank its claws into his pantaloons and mewed for milk. That was Turnip, decent to the core.

Arabella tried not to think about what Captain Musgrave had said. Or the very foolish things that she herself had been on the verge of saying in the garden, before he had stopped her. It was good that he had, she told herself. It had just been an impulse, born of the drama of the moment, and she would only have embarrassed both herself and him.

For a moment, when he had twined his fingers through hers, she had thought... but that was all nonsense.

Arabella blinked and tried to attend to what Lady Pinchingdale was saying.

“I had no idea what I was getting into when I married Geoffrey,” Lady Pinchingdale was saying, as she busily poured more tea into Arabella’s cup. Fragrant steam rose from the lip of the spout. “When he first told me about the spies, I thought he was making it up.” She set the teapot back down on the tray. “Unfortunately, he wasn’t.”

Arabella rested her saucer on one blanket-covered knee. “I hadn’t realized that spies were such a common household pest.”

Lady Pinchingdale made a face. “They’re worse than termites. They get into everything.”

“Chewing away at the fabric of state?” provided Pinchingdale, smiling at his wife.

“It ain’t his teeth I’m worried about. He had a knife, Pinchingdale. A knife!” When no one responded, Turnip crossed his arms across his chest and glowered. “Well, he did!”

“He didn’t seem to want to use it, though,” Arabella said thoughtfully.

Maybe it was whatever Lady Pinchingdale had slipped into the tea, but she felt the tension slipping away from her.

“I wouldn’t count on that,” said Turnip, pushing away from the mantel. “Deuced dangerous, relying on the goodwill of a scoundrel.”

“What strikes me about all of this,” Arabella said, taking another long swig of tea, “is how tentative it all is.”

“There’s nothing tentative about a knife at your throat,” protested Turnip.

Arabella wiggled forward under her blankets so that she was sitting properly upright. “Yes, but he wasn’t in any hurry to do anything with it. He scratched my arm, but that was only because I kicked him and it slipped. Last time, the knife wasn’t even a real one.”

“Last time?” asked Lady Pinchingdale. “This happened before?”

“Yes,” said Arabella. “I was borne off by a papier-mâché scimitar filched from one of the three wise men.”

She said it so drolly that both the Pinchingdales smothered smiles.

Turnip was not amused. “It wasn’t papier-mâché this time. Look at the scratch on your arm.”

“Are you trying to scare me?” Arabella asked, looking up at him over the rim of her teacup.

“Yes!” Turnip exploded. He dropped to his knees in front of her chair, moderating his tone. “Scare you into staying safe.”

“I’m not going to stay tucked away in my room for the next two days,” said Arabella. “That would just be silly. Not to mention incredibly dull.”

“We could barricade your door,” said Turnip, “and tell everyone you’re ill. You have the grippe — no, a fever. An extremely nasty, contagious fever.”

Lord Pinchingdale coughed on his tea. “Why not just say plague? That would keep the would-be murderers away.”

Turnip scowled. “That’s not funny.”

Arabella tilted her head up at him. He looked very odd from that angle. “You don’t find the Black Death amusing?”

“I don’t find your death amusing. I won’t stand here and see you murdered.” Turnip’s cheeks were flushed with emotion rather than tea.

“No one is going to murder me,” said Arabella, with more confidence than she felt. “Among other things, if whoever it is killed me, how would he ever find out where his list is? That’s probably a better safeguard of my health than all the goodwill in the world.”

Turnip looked unconvinced. “I still say the best safeguard is a few solid locks.”

“And some boils?” Arabella hitched up her blanket, which was slipping down over her lap. “It won’t work. Locks can be picked and walls can be scaled.”

“Not these walls,” said Turnip with confidence. “There isn’t a trellis. I checked.”

Their eyes met and Arabella felt all the heat in the room go straight to her cheeks. “Well,” she said, in muffled tones, “that is reassuring.”

“I feel like I’m missing something,” murmured Lady Pinchingdale to her husband, not quite sotto voce.

“A trellis, apparently,” said Lord Pinchingdale. “But you raise an interesting point. As long as our villain thinks you have the list, he has an interest in following your movements.”

“Which means,” his wife finished for him, her eyes bright, “that we can follow him.”

“Oh no,” said Turnip, catching their drift. “Don’t like it. Don’t like it a’tall. Won’t have Miss Dempsey being used as bait.”

“What I don’t understand,” Arabella intervened, before he could start steaming at the ears, “is why this... person persists in believing that I have his list in the first place. Unlike all of you,” she added, looking from Lord Pinchingdale to his wife to, at very long last, Turnip, brooding by the mantelpiece, “I have nothing to do with spying or spies.”

“You mean you had nothing to do with them,” contributed Lady Pinchingdale wryly. “I felt much the same way.”

Turnip, who had been brooding into the flames, turned abruptly. “It’s the notebook. It must have been in the notebook. Everyone saw Miss Climpson hand it to you.”

“Everyone being your sister, her friends, Miss Climpson, and Signor Marconi,” countered Arabella ticking them off on her fingers. “Somehow, I doubt that Sally has been augmenting her allowance by running an international spy ring.”

A slight grin tweaked one side of Turnip’s lips. “Shouldn’t put it past her,” he said fondly. “But you’re forgetting someone. Signor Marconi. No man who wears false mustachios can be up to any good.”

“Words to live by,” murmured Lord Pinchingdale. “You are right in part. Signor Marconi isn’t what he seems.”

“Ha!” said Turnip. “Thought I saw him lurking about the place. That third dragon from the left in Monday’s mummer play...”

“Couldn’t have been Marconi,” Pinchingdale interrupted him pointedly. “Marconi is, in fact, none other than Bert Marks of Tipton Downs, Yorkshire, and has never been farther abroad than Portsmouth.”

“Oh,” said Turnip. “How — ?”

“He was Henrietta Selwick’s voice teacher,” Lady Pinchingdale provided on her husband’s behalf, snuggling down on the arm of his chair. “Apparently Italians do better as music teachers, just as Frenchwomen do better as dressmakers, so Mr. Marks became Signor Marconi. Lady Uppington had his background thoroughly vetted before allowing him into the house. He’s a fraud, but not a traitor.”

“At least as far as we know,” Lord Pinchingdale qualified. “More honorable men have been known to turn traitor for the right sum. Marks — or Marconi — hasn’t exactly shown himself to be of sterling character.”

“It needn’t have been Marconi,” Turnip interjected. “What with the furniture flying and the porcelain breaking, anyone could have marched through that room and no one would have noticed. Half of Bath was climbing in and out the windows of the school that night.”

Arabella forbore to point out that he had been one of them. That would only bring up trellises again, and heaven only knew where that would lead them.

Lady Pinchingdale’s round blue eyes were even rounder than usual. “What sort of school is this?”

“Not one to which we are sending our daughter,” said Lord Pinchingdale. “We seem to be straying from the point.”

“One gets to much more interesting places that way,” murmured Arabella. Who was it who had said that to her? Oh. The chevalier. That reminded her of Mlle de Fayette’s visit earlier that night, and the flashes of lights in the garden that had set the whole bizarre series of events in train. “There was someone else in the garden that night, someone signaling with a lantern.”

“By Gad! That’s it!” Turnip slapped a hand on the mantel so emphatically that a china vase tottered on its base. “The lantern and the notebook. The chap with the lantern must have come to collect the notebook. It was always on that windowsill.”

“It’s true,” agreed Arabella from her nest of blankets. “I saw it there almost every time I was in the blue parlor. Sometimes it moved about from window to table, but no one ever claimed it.”

Turnip’s blue eyes were bright with excitement. “Would have been an excellent way to pass on information. So commonplace that no one remarked on it. Deuced clever when you think about it.”

Arabella hated to destroy his pretty theory. “There’s just one problem. The notebook went missing. I don’t have it. If our villain was the one who looted my room, why is he still bothering me?”

Turnip lost some of his glow. “Oh,” he said. “Haven’t worked that out yet.”

Lord Pinchingdale looked from one to the other. “The document that went missing would have been a single sheet of paper, closely written on both sides.”

Something snagged at Arabella’s memory. Like flotsam in a river, it bobbed briefly to the surface before drifting away again.

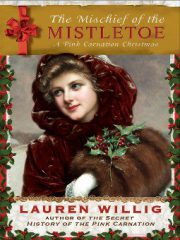

"The Mischief of the Mistletoe" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe" друзьям в соцсетях.