“She’s friends with Sally. Was friends with Sally,” Turnip corrected himself. He looked at Pinchingdale, struck by a sudden thought. “Arabella — I mean, Miss Dempsey — is one of her teachers.”

Pinchingdale’s eyebrow went up at that careless use of her first name, but he forbore to comment. He didn’t need to. If they could deploy Pinchingdale’s eyebrow against the French, Bonaparte would be all rolled up within the week.

“You don’t think that Catherine — ,” Turnip said hastily.

“No one is suggesting that Catherine took the list,” Pinchingdale pointed out. “Why would she take it? And what would she do with it?”

“Fair point,” said Turnip. “Do you know a chap named the Cheval-whatsis de la Tour de Something-or-Other?”

Pinchingdale took a moment for mental translation. “By which I presume you mean the Chevalier de la Tour d’Argent?”

“So you do know him!”

“Not well,” said Pinchingdale cautiously.

“I wasn’t asking if you’d ask the chap to stand godfather to your firstborn child,” said Turnip impatiently. “But if you’re looking for something rotten in the state of Bath, I’d say he’s a jolly good candidate.”

Pinchingdale shook his head. “Unlikely. Argent is one of the Comte d’Artois’s circle — and his father was one of the first victims of the guillotine. He has no cause to love the revolutionary regime.”

“That’s what they all say,” grumbled Turnip. “Well, you can’t expect me to believe that Miss Climpson is secretly a French spy, because I won’t.”

“That’s the curious thing,” said Pinchingdale thoughtfully. “There may be no French spy. The paper went missing in November. If it had fallen into the wrong hands, we should have had some word of it already. Instead...” He spread his hands in the universal gesture of perplexity. “Silence.”

Turnip squinted at him. “Which leaves us... ?”

“Absolutely nowhere,” said Pinchingdale wryly. “Or rather, at Girdings House for Christmas. So we might as well strive to enjoy it. I hear the dowager has mummers’ plays and morris dancers for us tomorrow.”

“Where’s my partridge in the pear tree?” mumbled Turnip.

“I think he was stepped on by the lords a-leaping,” said Pinchingdale amiably. “I wouldn’t worry too much about your Miss Dempsey. I doubt we have any spies on the loose at Girdings. The dowager would never allow it.”

Despite Pinchingdale’s reassuring words, Turnip did his best to keep an eye on Arabella, who half the time was out of the room, running errands for her aunt, who seemed to have a remarkable propensity for mislaying everything that wasn’t actually pinned to her person. Hard to keep an eye on someone who was constantly in and out of the room. Even harder when they weren’t officially speaking. They weren’t officially not speaking, either. They just sidled around each other, stealing glances when convinced the other wasn’t, and producing strained smiles when caught. It was all deuced confusing.

On the fourth day of the house party, with the mummers’ plays and morris dancers of Christmas Day behind them and the larger festivities for Twelfth Night still to come, the guests broke into their own separate amusements. Some of the gentlemen went off to practice their fencing in the long gallery; the ladies retreated to their writing desks. And Arabella went off to fetch her aunt’s shawl.

“Not the long one,” Aunt Osborne had instructed, giving Arabella’s hand an affectionate squeeze. “The one with the silk fringe. The one I gave you to give Rose to mend. She does a much neater job than my Abigail.”

Arabella was passing through one of the many interlinked reception rooms on her way back to the gallery, examining the tiny stitches on the shawl, when she looked up to see Hayworth Musgrave approaching her from the far side of the room. They were in one of the smaller drawing rooms, decorated in shades of yellow with accents of rose picked up in the porcelain arranged in cabinets to either side of the room.

“Arabella,” he said warmly. “How fortuitous.”

The winter sun slanted through the long windows, creating an illusion of warmth as specious as her new uncle’s smile.

“Captain Musgrave,” she said.

His smile widened. “I like to hear you call me so,” he said sentimentally. “It reminds me of... old times.”

“How nice,” said Arabella. “If you will excuse me, my aunt wanted her shawl.”

Captain Musgrave moved to block her egress. “We’ve seen so little of one another since the wedding.”

“Mmm,” said Arabella, noncommittally, wondering if it would be ridiculously rude to simply walk around him.

Musgrave took her murmur for assent. “I’ve been wanting a chance to talk to you.”

Arabella raised her eyebrows in polite inquiry, but said nothing.

Her silence seemed to fluster Captain Musgrave. He clasped his hands behind his back, puffing out his chest. “This nonsense about teaching at a school, there’s no need for that, you know.”

“I like it there.” She realized as she said it that it was true. She liked the bustle of it and the feeling of belonging. She liked the odd democracy of girls, all sharing the same meals and the same classes. She liked not having to worry about what she said or what she wore or about having to be grateful.

Captain Musgrave made no attempt to disguise his disbelief. “There’s no need to put a good face on it. You can come back, you know. We miss you.”

Once upon a time, those words from his lips would have set her hands tingling and her heart fluttering. She would have gone hot and cold and thrilled at the memory of them for days to come.

Now they left her with only one of those sensations: cold. She felt entirely cold, detached, as if she were a third party watching the conversation, unrelated to either of the participants.

“Is that the royal We?” she said coolly.

Captain Musgrave blinked. That hadn’t been in her script. “I mean, your aunt and I. Both of us.”

“How sweet.” If her aunt wanted her back, she could tell her so herself. Captain Musgrave might be her aunt’s husband, but he wasn’t her uncle. On an impulse, Arabella said, “You should ask Margaret for the season.”

“Margaret?”

“My next sister. She would be very glad to have the time in town. I believe she and my aunt would get along famously.” And they would, Arabella realized. Aunt Osborne would adore Margaret. How ironic to think that she’d had the wrong sister all along. And even if Margaret chose not to come to town, at least it would be her choice. She would have the chance. “Ask her. You’ll see.”

“I’m sure Margaret is lovely.” Brushing extraneous sisters aside, Captain Musgrave hastily returned to his prepared program. “But it’s you I’m concerned about.”

“How kind,” said Arabella.

Musgrave frowned. He wasn’t used to interruptions, at least not from her. That, Arabella realized, must be why he wanted her back so badly. He missed the audience, and the adoration.

“You do realize that our home is still your home. My marriage changes nothing.”

Arabella smiled brightly at him. “Except that now I have an uncle.”

He was even starting to look like one. A few more years and that paunch would be coming along nicely.

“Arabella...” Captain Musgrave took a step forward, oozing earnestness and bay rum cologne. “I hope you never thought...”

Oh no.

Arabella hitched her aunt’s shawl up over her arm. “As a friend of mine likes to say,” she said briskly, “I make it a practice to think as little as possible.”

“Friend?” Captain Musgrave was clearly put out at being interrupted mid-scene. “You don’t mean that Fitzhugh character?”

The way he said it put Arabella’s teeth on edge. She forced herself to say pleasantly, “Yes. I do.”

Captain Musgrave made an incredulous face. “I’m surprised to hear you call him friend. Have you heard what people say about him?”

“I’ve heard what people say about you,” said Arabella.

She didn’t need to elaborate. Any man who married a woman more than twice his age had to have a good idea of what the rumors were.

Captain Musgrave reddened. “The man’s a buffoon!”

Arabella thought of Turnip’s many kindnesses and her lips went tight. “The man is a gentleman. In the truest sense of the word.”

Captain Musgrave made a very ungentlemanly snorting sound. “With that income, a chimpanzee could be a gentleman.”

“Are you volunteering for the attempt?” Arabella didn’t wait for him to figure out how he had just been insulted. She swept on, buoyed by a cold anger that prickled like ice. “It’s nothing to do with income or properties or anything that can be measured in shillings and pence. It’s about character. I am sure you’re familiar with the concept.”

Captain Musgrave’s nose twitched, as though he smelled something unpleasant. “Watch yourself, my dear. From the way you say it, one would almost think you were in love.”

“In love? Me?” The idea was absurd. “Me? I — no. No.”

Arabella felt like an hourglass that had just been flipped over. Everything she thought she had known looked different viewed the other way around. Time ran backwards, through Miss Climpson’s parlor, her bedroom, Farley Castle, the street outside the school, Turnip grinning, frowning, picking her up off the ground.

Dizzy and disoriented, she shook her head and repeated the one word she seemed capable of remembering, “No. It’s... no.”

Captain Musgrave folded his arms across his chest, eyeing Arabella narrowly. “Everyone says he’s planning to marry that Deveraux girl.”

Something twisted in Arabella’s chest. The last of the sands shifted down, leaving the bulb empty.

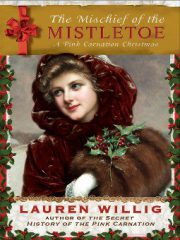

"The Mischief of the Mistletoe" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe" друзьям в соцсетях.