Through the smoke of the torches, Arabella could just make out the shapes of marble statues, freed from their winter burlap for the company’s delectation. A nymph stretched cold arms into the air above a dry fountain while topiary beasts roared from the sides of the path. She couldn’t tell whether they meant to protect her or to warn her away.

There was a blaze of light at the end of the path, more torches, this time arranged in a semicircle, as though for a ritual sacrifice. Arabella hurried towards them. They might be planning to put a maiden on the block, but at least she would be warm while they did it. Her fingers were freezing inside her gloves and her legs had lost all feeling several days ago.

A dog darted forward, nipping at her skirts, growling pleasurably as it attacked and killed her hem. There were more dogs underfoot in the clearing, tripping up yet more of the liveried footmen who were passing among the crowd with silver glasses full of a steaming liquid redolent of spices and spirits. A group of men milled just at the entrance to the clearing, quaffing spiced wine and kicking at the dogs, tricked out in fashionable multi-caped greatcoats, their curly-brimmed hats pulled down low over their eyes.

Arabella recognized most of them, although she doubted they would recognize her. There was Lord Frederick Staines, blond and arrogant, in line for an earldom; Lord Henry Innes, younger son of a duke, thick as a post; the Honorable Martin Frobisher, reputed to be anything but; Sir Francis Medmenham, dark and dissolute, but possessed of substantial properties both in England and abroad; Lieutenant Darius Danforth, formerly of the Horse Guards, also son of an earl, although there were rumors that he had been disowned. It had been all the usual sorts of reasons: drink, cards, and, if Arabella remembered correctly, seducing a young lady of good family. The lady’s family were clearly influential enough to protect their own; the name had never come out, but the general outline of the story had spread. The girl was rumored to have been all of sixteen, just a year older than Lavinia.

They were a motley lot, but they all had two things in common. All were monied. And all were unmarried.

They clustered around the low, three-legged braziers that had been provided for warmth, like the ones at Farley Castle.

Something pulled painfully in Arabella’s chest at the memory of Farley Castle. She felt suddenly, unaccountably alone.

Perhaps because she was.

It was ridiculous to feel nostalgic for something one had never had, or to regret the loss of a camaraderie that had been nothing more than the product of the moment. Even if she hadn’t — behaved like a hysterical shrew? her mind provided. Cut up at him like a demented fishwife? Even if she hadn’t put a precipitate end to their acquaintance, he would have forgotten all about her by now. He was the sort of amiable person who was sure to find friends wherever he went.

Arabella accepted a cup of mulled wine from one of the footmen and retreated to the shelter of a convenient tree, trying not to look as though she minded standing by herself. Again. There were other women present, but they seemed to be the ones doing all the hard labor of gathering the greenery. Typical. Lord Freddy and his lot wouldn’t want to get their gloves dirty. She could see the dowager’s granddaughter, Lady Charlotte Lansdowne, industriously piling mistletoe into a wicker basket, aided by a tall man in a cloak that looked as though it had been chosen more for warmth than fashion. Arabella didn’t recognize him, nor the man next to him, also travel-stained, talking to Miss Penelope Deveraux.

Who was just as striking as Arabella remembered. The man standing next to her was practically cross-eyed from staring. Put his tongue any farther out and he’d be panting.

Arabella sent Lady Charlotte a quick and unconvincing smile and hastily looked away, pretending to examine the rest of the party. There were some men who had ventured out into the wood, chopping away at the larger bits of greenery, the boughs of evergreen destined to decorate the hall of Girdings. One of them appeared to be attempting to chop down a tree using the wrong end of the ax.

Arabella’s hand jerked, slopping spiced wine over the already soiled leather of her glove.

It was dark away from the enchanted circle of torches, but there was enough reflected light to turn his hair to gold. He was very determinedly hacking away, his face averted from her, but there was no mistaking that profile.

Arabella hastily righted her cup before any more could spill, thinking very nasty thoughts about old family friends, the strange workings of Fate, and house parties generally.

Now she knew why Jane had asked about Girdings. And why she had smiled.

She was going to have to spend the twelve days of Christmas with Turnip Fitzhugh.

When Turnip spotted Arabella Dempsey, he did the sensible, mature thing. He began sawing at a tree with the wrong side of his ax.

On the long trip to Norfolk, as Sally’s mouth continued to move in an endless stream of school-related anecdotes, there had been far too much time for thinking. He had done his best to avoid it. He had challenged other drivers to race him; he had dragged Sally one day out of the way so he could attend a bout held by a much-praised pugilist and his local challenger; he had even paid attention to some of Sally’s stories. But that had still left plenty of time to fume and stew and stew some more as he revisited every baffling moment of their encounter in the blue drawing room.

Was it the money? He veered from anger to guilt as he recalled what that family friend of hers, that Miss Austen, had told him about the Dempseys’ circumstances. It had never occurred to him that she might need to work for her living or that his — hmm, how to phrase it? His incredibly well-reasoned and sensible activities might prove an impediment to that. In retrospect, she probably could have got into a good deal of trouble if he had been caught in her room. It would have been hard to pass that off as a visit to Sally.

It made him ashamed, to think how little he had thought. Not that there had ever been much need for thought before. He had muddled along fairly happily without it. But that had been all right for him, because, as Arabella had so succinctly pointed out, he was a man and he had money. There wasn’t any scrape he couldn’t buy himself out of, and he had certainly tried his hand at quite a few. Well, death. He doubted he could buy his way out of death, and there were probably some sorts of behavior — although he couldn’t think of any — that even thirty thousand guineas couldn’t redeem, but he couldn’t help but acknowledge the basic justice of her claim.

Someone tapped him on the shoulder. Turnip started, nearly dropping his ax.

“Two things,” said Geoffrey Pinchingdale-Snipe. “One. This is the pointy end. Not that. Two. One uses an ax to strike, not to saw. One uses a saw to saw.”

“Oh, ha bloody ha,” mumbled Turnip, but he reversed the ax. “Why is it that one uses a saw to saw but one doesn’t use an ax to ax? Bloody poor planning on the part of whoever wrote the language, I must say.”

“I don’t believe it was precisely planned.”

“Shouldn’t attempt a language without having a plan. That’s your problem, then, isn’t it?” said Turnip, watching Arabella as she accepted a silver cup of spiced wine from a footman and retreated against a tree.

“No,” said Pinchingdale with some amusement. “I believe it was your problem.”

That wasn’t Turnip’s problem. Turnip’s problem stood halfway across the clearing, wearing a violet pelisse and a bonnet instead of a hood. They were town clothes, not really appropriate for a country outing. Turnip wondered if they were all she had.

She lifted the cup to just below her lips, blowing a trail of steam off the surface of the liquid. It curled like smoke in the cold air.

“What do you find over there to occasion such interest?” asked Pinchingdale.

“Miss Dempsey just arrived,” said Turnip, trying to sound casual about it.

“Miss — ?”

Turnip found himself feeling defensive on her behalf. “Miss Dempsey. Third tree from the left. The tall girl, standing by herself. Blond hair, bluish eyes.”

Not that one could see either hair or eyes. The sides of her bonnet screened her face from view. She kept her head carefully down, from time to time taking a very small sip from the cup in her hand. It was as though she were trying not to be there. This was the Miss Dempsey he had known — or rather not known — in London.

“Ah. That Miss Dempsey.”

“Didn’t think you knew the others,” said Turnip. “Four Miss Dempseys, don’t you know.”

“No, I didn’t know,” said Pinchingdale patiently. It was clearly not a piece of information he found essential to his existence. “Do all of them cause you such consternation, or just this one?”

“Which was the pointy end of the ax again?” said Turnip.

Pinchingdale’s lips twitched into a smile. “Point taken. Or, rather, not.”

“It’s not about that sort of thing. Well, it ain’t,” Turnip said forcefully, although Pinchingdale hadn’t said anything at all. He didn’t have to. The man had the most bloody expressive eyebrows Turnip had ever had the misfortune of meeting.

Turnip shouldered his ax. “Miss Dempsey teaches at Miss Climpson’s. That’s all.”

“Miss Climpson’s?”

“Miss Climpson’s Select Seminary for Young Ladies. In Bath. It’s where the mater and pater farmed out Sally when the last governess refused to carry on.”

That had been one of Sally’s more spectacular triumphs. Either that, or her governesses had been a particularly weak-willed lot. Turnip’s tutors had shown considerably more staying power, even in the face of determined unwillingness to get past the first conju-whatever-you-call-it.

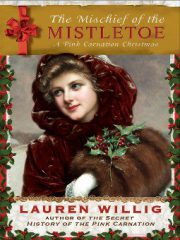

"The Mischief of the Mistletoe" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe" друзьям в соцсетях.